Why Many Power Tools Still Use Commutator Motors Instead of Brushless

Most power tools still run commutator motors for a very plain reason: they close the spreadsheet better. They’re cheap to manufacture at scale, plug straight into the wall or a simple DC pack, give fierce starting torque from a compact package, and have a service model that every repair shop on the planet already understands. Brushless brings better efficiency, control and durability, but it drags in magnets, silicon, firmware and new failure modes, and a lot of users will not pay that extra complexity just to drill a few holes on weekends or run a corded grinder that spends its life on short bursts.

Table of Contents

What this article assumes

You already know how a universal or brushed DC motor works, what a BLDC rotor looks like, and why everyone keeps talking about neodymium. You’ve seen the marketing slides that say “brushless = more runtime and power” and you’ve probably read at least one white paper that compares commutation schemes and efficiency curves.

So instead of repeating that, this is about why, after all that, catalog pages for drills, grinders, saws and sanders are still full of commutator motors. Not because engineers are unaware of brushless. Because product reality is messy.

The stubborn economics of commutator motors

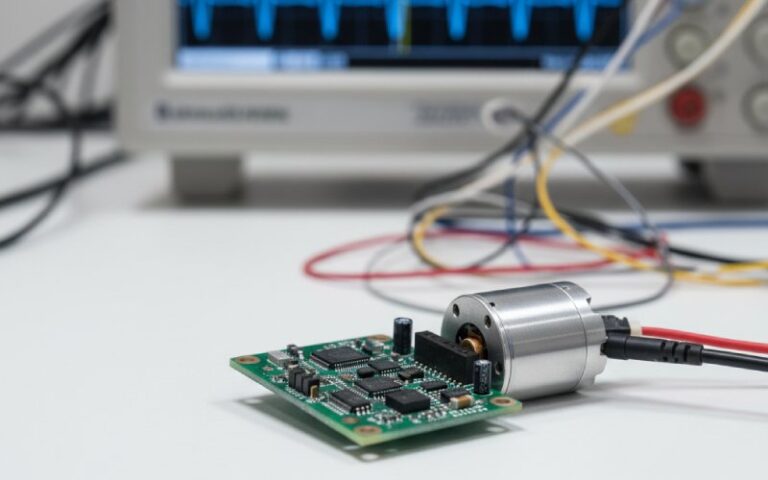

From a pure component view, brushless motors can even be simpler to assemble: no commutator, no brush gear, often fewer mechanical wear parts. Several motor vendors point out that the rotor and stator stack for a BLDC can be very production-friendly.

But tools aren’t just motors. They are bills of materials, test benches, repair manuals and marketing price points. And once you zoom out to the full drive system, the equation flips. Brushless requires a controller with power semiconductors, gate drivers, sensing or sophisticated sensorless algorithms, protection logic and usually some microcontroller. That electronics block often costs more than the motor steel and copper in a low-end tool. Industry comparisons still show that in mainstream consumer segments, a brushless drill or driver ends up roughly a quarter to a third more expensive at retail than an equivalent brushed model.

Commutator motors, by contrast, lean on eighty-plus years of manufacturing refinement. Winding, stacking, commutator assembly and impregnation are brutally optimized. The tech is so mature that several sources describe brushed motors as a “very low-cost” option not because they are clever, but because every possible cost-cutting trick has already been squeezed out of them.

That maturity cascades across the company. Fixtures, testing procedures, supplier contracts, rejects handling, training material for repair centers — all assume a commutator machine. Changing that is not just swapping one motor can for another; it is re-spending a decade of accumulated know-how.

AC corded tools: the universal motor still fits the wall

Corded drills, grinders, circular saws, corded sanders — most of them use universal motors with commutators. The question “why not brushless?” looks different once you admit the wall socket into the room.

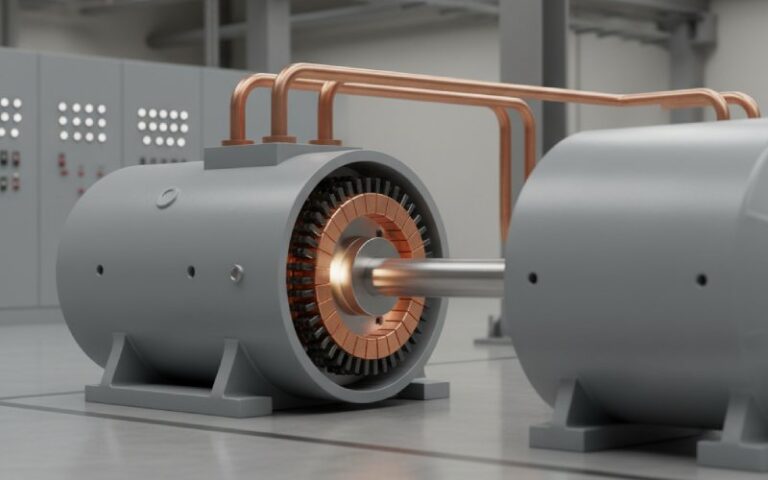

A universal motor is essentially a series-wound commutator machine that runs directly on AC or DC. It connects almost straight to mains through a trigger, maybe a triac or simple phase-angle control for speed. It can spin at tens of thousands of rpm, has high starting torque relative to its size, and fits well into compact housings.

To make a brushless motor run from the wall, you need a rectifier at minimum. In higher power classes you probably add power factor correction, some DC-link capacitors, proper isolation, gate drive, current sensing, firmware, and EMC fixes for all that fast switching. Now the “motor choice” has quietly turned into a full power-electronics project.

For a corded tool that is used in short bursts and lives next to a noisy vacuum or compressor anyway, the efficiency penalty of a universal motor — which can be quite significant at the smaller end of the power range — just does not move the business needle enough to pay for that electronics stack.

There is also certification inertia. A class of universal-motor tools has a safety and EMC story that regulators and test labs know well. A high-frequency inverter driving a BLDC adds a different pattern of conducted and radiated noise, different failure modes, and different tests. You can absolutely engineer around that; many premium corded tools already do. But for the mid and low tiers, it is one more reason to stay with the devil you know.

Cordless tools: why brushed survives at the bottom of the range

Battery tools are where brushless has made the loudest entrance. Extra efficiency and controllability directly stretch runtime and let you sell more “work per charge.” Sources regularly highlight that brushless power tools give noticeably longer battery life, better torque density and cooler running.

So why is the cordless aisle still full of brushed drills and drivers?

Because not every buyer uses those tools all day. A homeowner who drives a handful of screws once a month does not care if a charge lasts thirty minutes or forty. They care if the kit is twenty dollars cheaper on the shelf. For that buyer, the combined cost of a BLDC motor, magnets and control board is pure overhead they never see.

On top of that, brushed DC motors in cordless tools are often series-wound or permanent-magnet units that are already very compact and punchy. Their low-speed torque and overload tolerance are quite good if you only ask them to sprint for short jobs.

There is also segmentation strategy. Brands deliberately reserve brushless and “smart” control features for higher price tiers: trade-focused lines, premium kits and halo products. Entry-level brushed tools serve as feeders into the ecosystem: same battery mount, same chargers, much lower buy-in. Switching the bottom tiers to brushless would blur that structure, and marketing teams rarely enjoy losing their ladder.

Reliability: not as one-sided as the brochures suggest

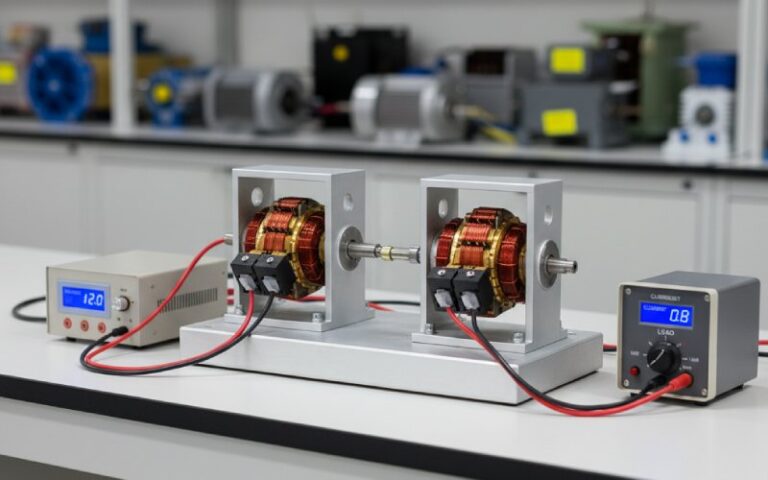

Brushless motors remove brush wear from the equation; no carbon dust, no commutator erosion. Technical articles and datasheets consistently state that brushless motors can achieve longer lifetimes, especially in continuous duty, compared with brushed designs limited by mechanical contact wear.

But that is only half the story a tool designer has to live with.

A commutator motor has obvious, physical wear elements. When brushes reach their limit, performance drops in a very visible way, and a service center can swap them in minutes. Spares are cheap, diagnostics are straightforward. For many professional users, this predictability is comforting: they know what failure looks like and what it costs.

Brushless tools shift the weak points. The motor itself may run almost forever, but the electronics now bear the brunt of surges, dust ingress paths, condensation, mis-wired generators, static events, and the occasional user who runs masonry dust straight into every vent on the tool. A blown MOSFET does not announce itself gradually. It dies, often taking the driver IC and a trace or two with it.

In regions without dense service networks, that difference matters. Replacing brushes is something even a small repair shop can handle with basic tools. Diagnosing and re-working multilayer PCBs inside sealed housings is another world. So a brushed grinder might officially “wear out faster”, yet stay in service longer simply because local technicians can keep resurrecting it.

Materials, magnets and supply chain risk

Brushless motors normally rely on strong permanent magnets, very often based on rare-earth materials like neodymium. Industry commentary around industrial and motion-control products frequently notes that this ties BLDC cost and availability to a somewhat volatile materials market.

Several brushed motor lines used in demanding applications, on the other hand, are explicitly marketed as rare-earth-free: they use only copper, steel and common magnet materials, and still meet torque requirements. This is convenient if you are making millions of units and do not want your cost base exposed to geopolitical or mining shocks.

In a battery tool, once you have committed to a BLDC architecture, magnets are a cost of doing business and you accept it. In a corded angle grinder that is supposed to stay inexpensive across many seasons and currencies, not needing neodymium at all is quietly attractive.

There is also the supplier ecosystem. Commutator motors are a commodity. Hundreds of factories can quote them; design changes can often be cross-sourced with modest effort. BLDC motors and matched controller boards for tools are still less interchangeable. That dependence on specific vendors can become another hidden argument for staying with brushed in some product lines.

System-level behavior: torque, speed and abuse

From the physics side, universal and series-wound brushed motors bring three traits that suit power tools very well: high starting torque, willingness to run at very high speed, and tolerance for short overloads.

You feel this in a corded circular saw that slams into load without much hesitation, or a grinder that happily digs into a cut until the operator backs off, not the control loop. Brushless tools can absolutely match or exceed this performance, but only if the firmware allows it and the electronics can take the peaks. Someone has to choose between a soft, protective profile that preserves silicon and a more aggressive one that feels “angrier” in the hand.

With brushed tools, the line is simpler. No microcontroller deciding anything. The motor draws whatever the mains, armature and wiring allow, and the weak link is usually the copper or the thermal limit of the insulation. For some categories, that brute-force behavior aligns with user expectation better than a clever current-limited response.

Noise and EMI are interesting too. Classic articles point out that commutator machines generate mechanical and electrical noise due to brush contact and sparking. Brushless drives are quieter both acoustically and electrically in many cases, especially at constant speed. Yet in construction or metalworking environments, the difference is often irrelevant next to the material being cut or ground. Builders do not select a demolition hammer for its whisper mode.

So, in practice, the advantages of brushless behavior show up strongest where users spend long periods at partial load or care about subtle control — for example, high-end impact drivers and precision screwdrivers. In short-burst “abuse-tolerant” tools, the coarse but predictable behavior of a universal motor still works well enough.

A compact comparison

To keep things concrete, it helps to summarize the system tradeoffs the way a design team might see them.

| Design factor | Commutator (universal / brushed) motor tools | Brushless motor tools |

|---|---|---|

| Upfront system cost | Very low motor cost; minimal electronics, often just switch or simple control. Manufacturing and tooling are deeply optimized after decades of use. | Motor can be simple but requires a full electronic drive; controller plus magnets typically raise product cost by tens of percent in mainstream power tools. |

| Power source fit | Universal motors run directly from AC or DC with simple circuitry, suiting corded tools very well. | Needs DC bus and inverter; fine for battery tools, more complex for mains products where additional rectification and filtering are required. |

| Efficiency and runtime | Lower efficiency due to brush and commutator losses; acceptable for intermittent duty where energy cost is minor. | Higher efficiency and cooler running, giving noticeably longer runtime in cordless tools and less heat stress during continuous work. |

| Lifetime and service | Brushes and commutator wear, but failure is gradual and serviceable; brushes are cheap and easy to replace worldwide. | Motor core often outlasts the tool, yet electronics can fail abruptly; repair usually needs board-level work or full module replacement. |

| Materials and supply chain | Often rare-earth-free, using common steels and copper; wide supplier base for motors and spare parts. | Relies heavily on high-performance magnets and specific controller platforms, tightening supply and exposing cost to magnet pricing. |

| Typical positioning | Entry-level cordless tools, many corded tools, cost-sensitive professional gear where abuse tolerance and repairability matter more than runtime. | Premium cordless lines, tools marketed on runtime and power density, and applications where lower noise and fine control sell at a premium. |

How product history weighs on every new design

Even if a manufacturer wanted to switch an entire family of tools to brushless tomorrow, they carry history.

There are service manuals written around armatures and commutators. There are warehouses full of replacement field coils and brush sets. There are regional partners whose business model is built on fixing those machines quickly. There are fixtures in factories sized for specific stator stacks and rotor lengths.

Each new brushless variant becomes, at first, an outlier: different test scripts, different field failures, different spare parts process. Over time the balance shifts — many brands are already at the point where their flagship cordless systems are almost entirely brushless. But the long tail of existing designs means commutator motors keep showing up on shelves even as the “future” is heavily advertised as brushless.

Reality is not a clean handover. It is a thick overlap.

Where brushless really changes the game

It would be unfair to pretend commutator motors are equal everywhere. The areas where brushless is genuinely hard to argue against are increasingly clear: tools running all day on batteries, applications that need precise torque control, environments where noise is a real constraint, or where service access is poor and you want every hour of extra life you can get. Technical comparisons consistently list higher efficiency, longer lifetime and quieter operation as strong brushless advantages.

As controller ICs and integrated driver modules keep getting cheaper and more capable, the electronics penalty shrinks. The magnet story might soften as well if alternative motor topologies or better magnet supply options mature. At some point, the “why not brushless?” question will win in more and more categories by simple arithmetic.

But today, if you stand in front of a rack of corded grinders or budget cordless drills and wonder why they still use commutator motors, the answer is quite plain.

They are old, but they are not yet wrong. The economics still line up, the power density is already good, users know how they fail, and every part of the ecosystem around them — from copper winders to small repair shops — is tuned to keep them spinning. Brushless is the future for many tools. Commutator motors are the present for many more, and that present is not finished yet.