Why Your Power Tool Motor Sparks at the Commutator (Focus on Tool Specifics)

Most of the sparks you see through those vent slots are either perfectly normal or a quiet warning that the tool is burning itself up. The trick is simple: watch how the sparking changes with load, speed and time, and you can usually tell whether to keep cutting, pull it apart, or retire it before it cooks the armature.

Table of Contents

You already know the theory. This is what the sparks are really saying.

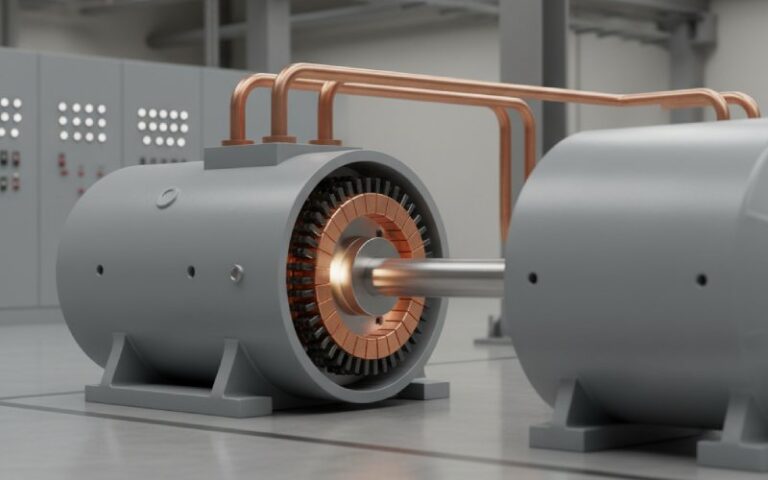

You know what a universal motor is. You know what a commutator does. So we’ll skip the textbook and talk about what you actually see when you pull the trigger on a drill, grinder, saw, planer or rotary hammer.

A healthy brushed motor throws a tight, small orange glow at the trailing edge of each brush. At no-load you might see a thin line of tiny arcs; when you put the tool to work, those should stay modest or even calm down a little. That kind of behavior has been called “normal small arcs at the trailing edge” and it’s accepted for brushed AC / universal motors.

When the sparks get longer, brighter, noisy, start running around the full 360° of the commutator, or they flare up under load instead of settling, the motor is telling you something is wrong: brushes, commutator, windings, mechanics, or how you’re using the tool. Excessive sparking has been tied repeatedly to worn brushes, reduced spring pressure, rough commutator segments, carbon dust in the slots, or shorted armature windings.

That’s the level we’ll stay at: what the spark pattern means, tool by tool, and what to actually do about it.

Normal sparking vs “this thing is eating itself”

You can treat the commutator like a simple indicator. You don’t need a scope, just eyes, ears and nose.

Small, dim sparks that stay tight to the commutator, maybe a light halo in a dark room, usually go in the “keep working” bucket. Bright yellow-white fire, especially if it’s wrapping around the commutator, synced with a hot electrical smell, is the “stop now” bucket. Heavy arcs and overheating are also listed as key symptoms of a sparking complaint in universal motor guides and brush manufacturer charts.

To keep this practical, here’s a table that links what you see to what’s probably happening inside, with tool-specific flavor.

| What you see at the commutator | What’s probably happening inside | Typical tool situations | First move in the shop |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tight, low orange sparks, mostly at trailing edge of the brush. Sparks shrink or stay similar when you load the tool. | Normal commutation. Brush grade, spring force and commutator film are in the acceptable band. | Mid-range corded drill free-spinning, trim router at moderate speed, jigsaw running in air. | Treat this as your “baseline” visual. No action beyond occasional cleaning and brush checks. |

| Occasional brighter “streaker” sparks at one point around the commutator, sometimes with a corresponding darker or lighter bar. | Single high bar, proud mica, or slight commutator eccentricity. Brush bounces as it passes that point. | Mitre saw that’s been slammed into work all day, planer that’s taken a hit, older drill that’s been dropped. | Stop before it becomes a full fire ring. Inspect commutator for a raised bar or uneven undercut; light, correct re-surfacing or armature replacement if you have the tooling. |

| Long, bright yellow-white sparks that wrap most or all the way around the commutator. Often with heat, smell and loss of torque. | Shorted armature turns, bad insulation, or serious commutation failure. Often burned commutator segments to match. | Angle grinder that’s been leaned on hard in steel, circular saw stalled in thick stock, old drill that’s already been hot a few times. | Kill power immediately. Strip the tool. If you see burned bars or dark, cooked windings, treat the armature as scrap or send it for rewind. Don’t keep “trying it”. |

| Sparking that is modest at no-load but gets heavy and scattered as soon as you put real load on the tool. | Brushes may be worn, wrong grade, poorly seated, or commutator film is damaged. High current under load makes the weak spots show. | Brush change to a non-OEM set in a grinder, planer or SDS drill. Shop vac or dust extractor motors after brush replacement. | Check brush length and spring pressure. Confirm you’re using a compatible brush grade. Clean commutator slots, run-in gently at no-load to seat the brushes before serious load. |

| Heavy sparking appears mainly when the tool bogs or stalls; almost disappears when you ease off. | Tool is simply being overloaded. Current spikes, commutation margin disappears. Repeated abuse still damages brushes and commutator over time. | 4½” grinder on a big cut with a cheap thin cord; circular saw ripping dense hardwood; demolition hammer forced sideways into concrete. | Change how you’re using it: lighter feed, sharper accessories, better extension cord gauge, let it cool. If sparking has already damaged brushes, inspect them. |

| Random, dirty-looking sparking with black dust and a dull commutator surface. | Carbon dust buildup, contamination or poor commutator film. The brush isn’t seeing a clean surface, resistance varies segment to segment. | Tools used in very dusty environments: masonry grinders, concrete saws, planers, random orbital sanders. | Blow out the motor (carefully), clean the commutator and brush box, and check that vents and filters are not clogged. Replace brushes if they’re glazed or chipped. |

You’ll notice what’s missing in that table: we didn’t talk about “what a commutator is”. You already know that. More useful is to connect the visible spark pattern with the specific abuse your drill, grinder or saw has actually seen.

Tool-by-tool: how sparking usually plays out

Different tools push their motors in different ways. The motor design is similar, but the abuse profile isn’t.

Drills and drivers

Corded drills and SDS rotary hammers spend a lot of time starting and stopping. High inrush, lots of trigger work, frequent stalling when a bit binds. Brief sparks that flare right as the tool stalls and vanish as soon as you ease the trigger are just what you’d expect. When the drill is spinning freely and you already see long sparks licking around the commutator, that’s not start-up current anymore; that’s usually wear or damage.

On drills with variable speed triggers, low-speed running at high torque is a tough combination. The field is doing its job, current is high, ventilation is poor. If you’re seeing the brightest sparking during slow, high-torque work, assume you’re stressing both the brushes and commutator. Short use in that zone, then full-speed running in air to cool, stretches tool life more than any cleaning trick.

Angle grinders and cut-off tools

Grinders are often the first tools where people notice motor sparking, mainly because the tool itself already throws metal sparks out the front. So it all blends and gets ignored.

Inside, grinders punish their motors. Long duty cycles, near-continuous high load, fine dust, and often undersized extension cords dragging the input voltage down. Low voltage with high mechanical load means high current, weak field, wide commutation angle and more sparking. Several motor articles point directly to overload and voltage issues as common causes of internal arcing.

When a grinder is healthy, you’ll see a small orange glow through the side vents, even under load. It shouldn’t look like a ring of lightning. If the sparking suddenly jumps after you change brushes, think “wrong brush grade or poor seating” before you blame the armature. If it jumps after a particularly brutal cut with the disc almost stalled in the kerf, suspect that you’ve cooked the commutator film or damaged a few turns.

Grinders are also very sensitive to vibration. Slight bearing play or a bent spindle translates into commutator runout and brush bounce, which shows up as those “streaker” sparks at a particular point in rotation. Maintenance guides for rotating machines point out that eccentric commutators and machine vibration are classic sources of brush sparking and commutator damage.

Circular saws and mitre saws

These tools usually run at high speed with fairly consistent load in the cut. They don’t see the constant stall events that drills do, but they do see shock loads when someone forces the blade through a knot or pinches it in a closing kerf.

If a saw has been overloaded often, you’ll sometimes notice sparking that’s fine at idle but flares as soon as the blade enters the wood. That’s the “load-sensitive” pattern from the table and often tells you the brushes and commutator have seen enough heat cycles. A worn commutator that’s slightly out-of-round can add that single-point streaking, again at the same spot every revolution, just like in grinders.

Mitre saws in particular get slammed into work and then snapped back up. That stop-start motion is rude to bearings. As bearings wear, the rotor can sit off-center. Forums discussing DC and universal motors often mention uneven air gaps and magnetic misalignment as contributors to excess brush sparking; the same physics applies here.

Planers, sanders and routers

These tools often run near max speed, with variable but usually modest torque. Their motor sparking problems are often more about dust than pure load.

Fine dust can coat the commutator, lodge between bars and build up into conductive paths. Brush and commutator troubleshooting charts explicitly call out contamination and dust as a cause of brush arcing and erratic commutation. If the tool lives in MDF or concrete dust, assume the guts are dirty long before the outside looks bad.

Routers and trim routers often show “flickery” sparking at intermediate speeds when run with electronic speed control. That’s not automatically a failure. But if the flicker grows into fat, bright arcs that stay even at full speed, now you’re beyond simple control behavior.

Rotary hammers and demolition tools

Rotary hammers load the motor heavily and for long periods. A lot of them sit right on the edge of sensible current for their frame size. Some sparking is baked into that compromise.

The main thing to watch is change over time. If you have an SDS hammer that has always shown a modest, steady glow and then, after a particularly long session in dense concrete, starts throwing bigger and noisier sparks with a hint of a burnt-epoxy smell, that’s your hint. Worn brushes, misaligned holders or early armature damage: all are documented causes of increased sparking once operating current stays high for long runs.

What changed inside the motor when the spark pattern changed

It helps to have a approximate mental picture of what actually changed when the sparks got ugly.

If the sparks got longer and brighter right after you changed brushes, but only at load, chances are you changed the electrical contact properties: new brush grade, new seating, new spring pressure. Brush guides repeatedly flag wrong brush material, inadequate spring force and poor seating as common arcing causes. The commutator itself might be fine; it’s the interface that’s unhappy.

If the sparks are tied to a single angular position, something is no longer geometrically true. A high bar, raised mica, eccentric commutator or shifted rotor. Motor maintenance literature is blunt here: eccentric commutators and mechanical vibration appear near the top of “sparking causes” lists. You don’t fix that with more cleaning. You either machine it or replace the armature.

If the sparks appear mainly when the tool is heavily loaded and they more or less wrap around the commutator, internal copper is probably getting too hot. Insulation breaks down, turns short, and now you’re watching a small arc-welder inside. Repair sites and Q&A boards agree: when you see a continuous ring of sparks around the commutator combined with burned spots, the armature is usually shorted and not worth “running to see if it clears.”

If the sparks are dirty, scattered and accompanied by black soot, that’s contamination. You may have a perfectly good armature buried in carbon dust and abrasive grit. The fix is often cleaning and brush replacement, not a new tool.

When to keep using the tool, and when to stop

You can make the decision without a fancy chart, but it’s nice to know those charts exist. Carbon manufacturers and motor specialists publish “spark level” indicators (Mersen’s commutation indicator, the old Westinghouse spark chart) with acceptable bands for normal operation in brushed machines. Universal motor guides say the same thing in plainer words: small, dim, consistent sparks are fine; bright, noisy, persistent arcs with heat and smell are not.

For power tools, a reasonable rule set looks like this, kept simple:

If you only see small orange sparks that don’t grow under normal work and the tool doesn’t run hot or smell burnt, it’s usually safe to keep in service.

If the sparking has recently increased, especially after a hard job or brush change, stop and inspect before you put the tool back into heavy rotation. Often you’ll catch a brush or commutator issue early.

If you see a near-continuous ring of bright sparks, hear a harsh electrical crackle, or smell burnt insulation, treat the tool as failed until you prove otherwise on the bench. An armature that has already started to carbon-track or burn bars rarely “heals”; running it longer just damages the commutator more deeply.

And in any environment with flammable dust or vapors, even what would be “normal” sparking in a drill or grinder can be the wrong tool choice. That’s a design decision, not a maintenance problem.

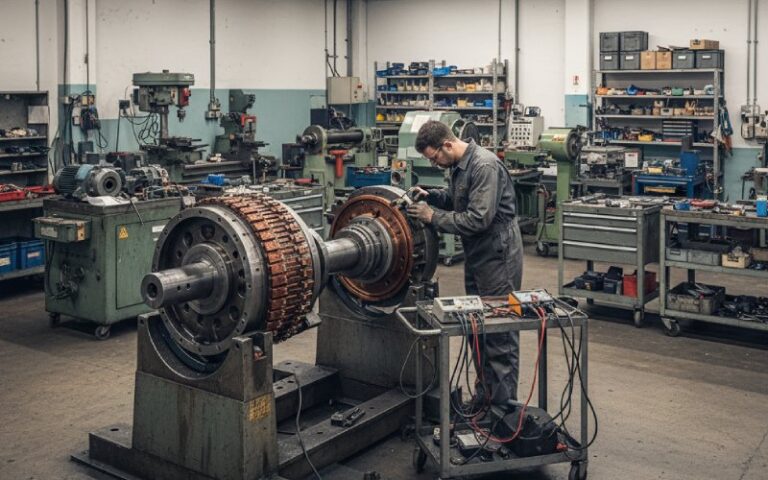

Bench habits that keep commutators honest

Once the tool is on the bench, most of the useful work is basic, not exotic.

Unplug it. Strip down to where you can clearly see both brushes and the commutator. Blow out dust, but not like you’re trying to spin the rotor with compressed air; you’re just trying to get rid of the conductive powder and grit. Many repair guides specifically recommend cleaning out trash and dust around brushes and commutator before making deeper calls, because carbon between segments alone can cause arcing.

Check brush length against the manufacturer’s limit or at least against new stock. Articles on brush replacement point out that once brushes are past their wear line, you’ll often see sparking, power loss and a burning smell long before they literally disappear. Confirm that the springs still push with some authority and that the brush can move freely in its holder.

Look closely at the commutator. You’re not looking for shine; you’re looking for uniformity. Even color, even bar heights, no obvious flats, no raised segments, no blue or blackened spots. The detailed “commutator condition guides” from Helwig and others show exactly how problems start as subtle discoloration, then progress to bars with different appearance and then to real mechanical damage.

If you have the tooling and the job justifies it, you can undercut mica, reface a slightly rough commutator and properly bed in new brushes. If this is a cheap homeowner drill, the honest answer is often to replace the armature or the whole tool instead of trying to re-machine a badly damaged commutator.

Final thought: treat the sparks as a diagnostic, not a drama

The sparks at the commutator are not there to scare you. They’re just visible evidence of how well the motor is commuting current at that moment.

If you get used to watching them, across several tools and over time, you start to recognize patterns. Normal halo in an unloaded grinder. Slight streak after a planing accident. Sudden ring of fire after someone stalls a saw in a knot. Each pattern maps to a mechanical or electrical story inside the tool.

Once you read those stories reliably, you stop guessing. You stop scrapping tools too early. And you also stop running the ones that are quietly cooking their armatures to death. The sparks haven’t changed; only how much useful information you pull out of them has.