Why Is Only Half The Insulation Removed From A Commutator?

In the classic classroom “wire-and-battery” DC motor, only half the insulation is removed so that the coil gets current only during the half-turn when the magnetic torque helps it, and is left open-circuit when the torque would fight the motion. Strip everything and the motor stalls or just jitters. Strip nothing and it never starts. Half-bare, half-insulated turns that cheap little loop of wire into a crude but effective commutator.

Table of Contents

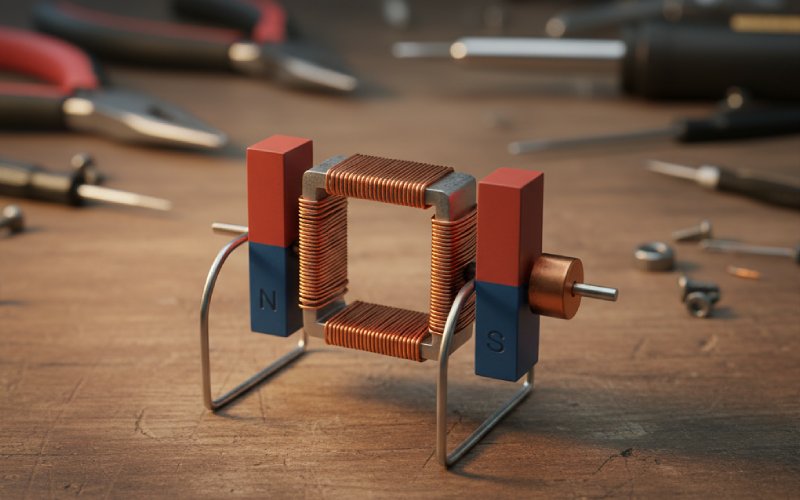

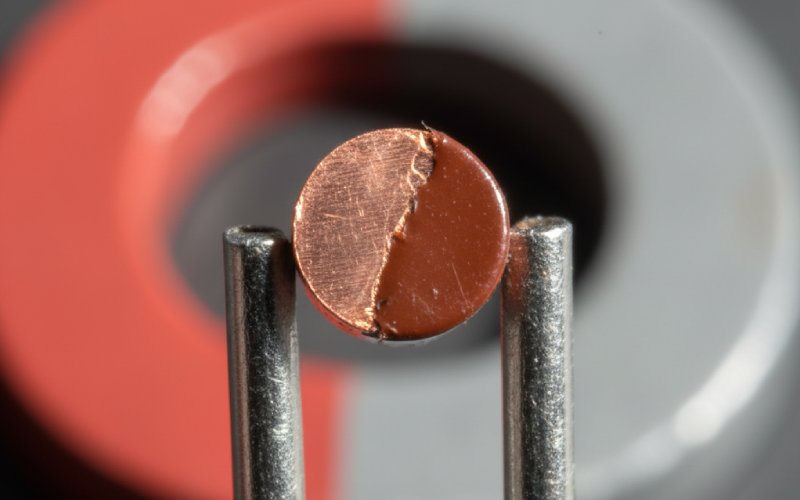

What “half the insulation removed” actually refers to

Let’s pin down the hardware, because different people mean different things by “commutator”.

In the school or first-year lab motor, the “commutator” is literally the enamelled copper wire ends of the rotating coil resting in two supports (pins, paper clips, hooks). You scrape the enamel off:

- one end: completely bare where it touches the support

- the other end: bare only over roughly half the circumference, with the other half still insulated

Viewed from the side, each end looks like a circle of copper, but on one of them the copper is exposed only on one semicircle. That half-bare end is the commutator segment. When the bare semicircle faces the support, current flows. When the insulated semicircle faces the support, the circuit opens. Simple, but not random. Tutorials, lab notes, and Q&A threads all describe this 180-degree bare / 180-degree insulated pattern as the key to getting continuous rotation.

So “only half the insulation removed” means: only about 180° of the circumference of one coil end is scraped clean where it rides on the support.

What goes wrong if you strip all the insulation?

Imagine ignoring the instructions and scraping both ends completely clean.

Now the coil is an electromagnet all the time the battery is connected. The direction of the current never changes relative to the coil, so the direction of the magnetic moment never changes either. The torque on the coil in a uniform field is proportional to the sine of the angle between the coil’s magnetic moment and the field.

That means:

- from some starting angle, the torque accelerates the coil toward alignment with the field;

- once it passes alignment, the torque naturally reverses and tries to pull the coil back.

With continuous current, the coil simply hunts for the lowest-energy position and sits there, glued magnetically to the preferred orientation. Several classroom notes say exactly this: if both sides are fully stripped, the coil is “always a magnet” and tends to stay stuck pointing at the permanent magnet rather than spinning.

You might see a momentary twitch when you first connect power, but not a sustained rotation. If friction is low and everything is perfectly symmetric, you might even get a little rocking back and forth. Not what anyone would call a motor.

So removing all the insulation makes the commutator stop being a commutator. You lose the “switching” function entirely.

Half-bare = 180° on, 180° off

The half-bare wire solves that by creating a simple time pattern:

- approximately 180° of rotation with current on;

- approximately 180° with current off.

The idea, as several lab manuals and explanations put it, is that the motor uses current to accelerate itself through the “good” half of the turn, then coasts through the “bad” half on momentum while the circuit is open.

During the powered half-turn the forces on the two sides of the coil both push it in the same rotational sense. Once the coil has swung to where those forces would reverse direction and start braking, the bare patch rotates away from the support, the insulated patch comes under the support, and the current stops. No current, no torque, so there is nothing to pull the coil back. It just keeps moving because it is already in motion.

By the time it has turned another half-turn, the bare patch comes under the support again, the current snaps back on, and the cycle repeats.

So “only half the insulation removed” is really “torch on for half a revolution, off for the other half”.

Why it has to be the right half

Removing any random 180° of insulation would not be enough. The bare half has to be aligned with the coil orientation where you want the current to exist.

In the usual build, you mark the coil in a vertical plane between north and south pole faces. Then you scrape the upper half of one end of the wire, leaving the lower half insulated, making sure both ends expose the same side of the wire relative to that vertical coil orientation. Classroom instructions and lab sheets are very explicit about this orientation, precisely because getting it wrong makes the motor fail in confusing ways.

If you scrape the wrong half, you end up energising the coil mostly when the torque would oppose the direction you’re trying to spin. The result is a strong tendency to park itself or to run only when you flick it in a “lucky” direction.

So the half-insulated commutator is not just about the amount of insulation removed. It is about phase: aligning the conduction window with the angular region where the torque has the sign you want.

Comparing different stripping patterns

Here is a summary of what actually happens for different “how much insulation did we scrape off?” choices in this kind of motor:

| Strip pattern on coil ends | Current over one turn | Torque pattern | Likely behaviour |

|---|---|---|---|

| Both ends fully stripped | Current flows for all angles; coil is always an electromagnet | Torque pulls coil into alignment, then reverses and brakes it after it passes alignment | Coil snaps to a stable angle and stays there; maybe a twitch, no sustained spin |

| One end fully stripped, other end bare over correct 180° | Current flows only over half the turn, timed so torque always helps motion during that half | Powered half gives a push; unpowered half lets the coil coast without braking | Reliable “half-wave” motor; spins in a preferred direction once nudged |

| One end fully stripped, other end bare over wrong 180° | Current flows over half the turn, but mostly in the braking region | Torque fights the motion more than it helps | Motor stalls or runs only intermittently; often just vibrates near one position |

| Tiny bare patch, much less than 180° | Current pulses briefly once per turn | Short torque impulses, large dead zone | Very jerky, may never build enough speed to coast through the off-region; tends to be unreliable in practice |

This is why good lab sheets talk not just about “half the insulation” but also about the angular extent and orientation of that stripped section.

Why half a turn is a sweet spot

Assuming the reader is comfortable with torque-versus-angle curves, there is a nice way to visualise why “about half” is attractive.

Take a simple rectangular coil, one turn, N = 1, area A, in a uniform field B. The instantaneous electromagnetic torque magnitude is proportional to IAB sin θ, where θ is the angle between the coil normal and the field. If you allowed current to flow all the time with a fixed direction, the average torque over one revolution is zero, as expected; the positive part cancels the negative part.

Now clip the current waveform so it exists only for 180° centred on the angles where sin θ has the sign you want, and is zero elsewhere. The average torque over a turn becomes non-zero, and the negative-torque region is trimmed away. That “windowing” of the torque is exactly what the half-insulated commutator is doing, just with very crude timing.

If you made the window much longer than 180°, you start letting current flow again in part of the region where torque would oppose motion. If you make it much shorter, you reduce average torque and force the rotor to rely heavily on inertia and low friction. Around 180° is a practical compromise for a motor built from a battery, a magnet, and whatever wire and paper clips happened to be in the drawer. Lab notes that discuss this carefully often quote “conduction prevented over 180° of the rotation” as the design target.

The half-insulated construction gives that 50% electrical duty cycle without requiring any extra parts beyond a knife or sandpaper.

The “dead” half-turn is not wasted

People sometimes worry that the non-powered half of the cycle is wasted. In a lab motor you are not chasing efficiency. You are chasing a clear demonstration of torque direction and of commutation.

During the off half-turn:

- the stored kinetic energy of the spinning coil carries it through the region where the magnetic torque would have opposed motion;

- the absence of current means no extra heating of the coil or the contacts during that interval;

- mechanically, the brushes (wire supports) see less average contact current, which limits burning and pitting in a construction that is already very marginal.

Several teaching resources explicitly describe that phase as a coasting interval “once every revolution” where the coil is not attracting the magnet and just continues in the same general direction.

So the motor is trading continuous torque for stable direction and simplicity.

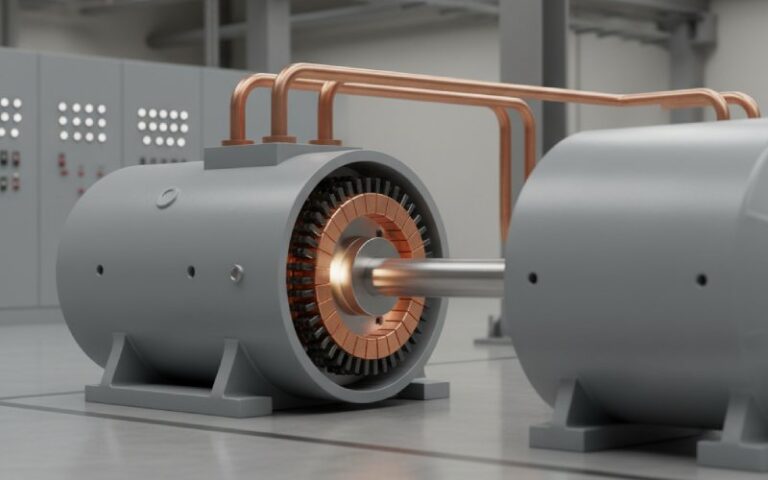

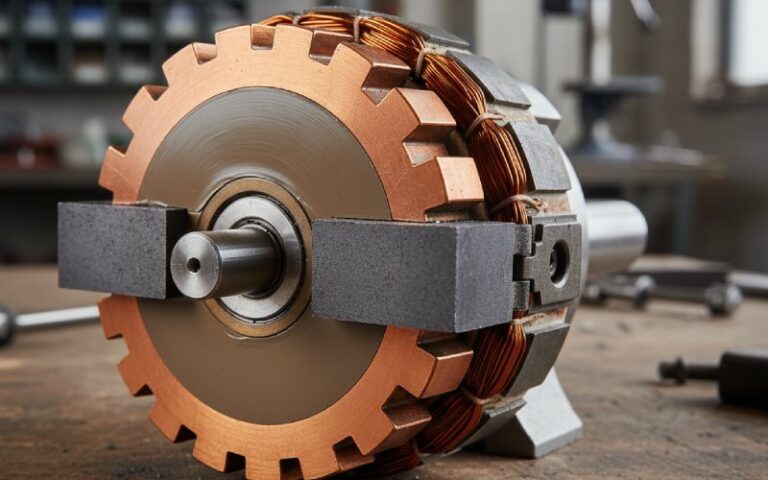

Connection to real DC commutators and partial insulation removal

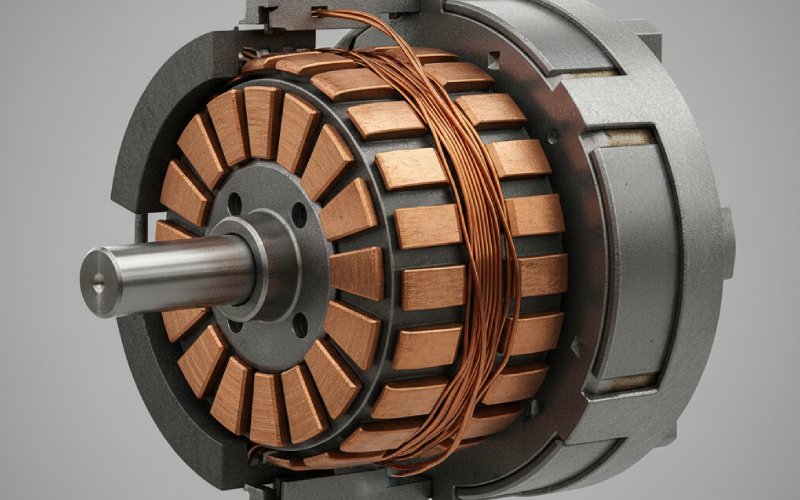

The half-insulated wire trick is a toy-level echo of what large DC machines do with proper copper-segment commutators.

In a real DC motor or generator:

- the commutator is built from many copper bars, separated by thin mica or similar insulation;

- the mica is machined or “undercut” a little below the level of the copper segments, so the brushes only rub on copper, not on the insulating material;

- the geometry and brush width are chosen so that, while a segment is under a brush, the associated armature coil is being switched from one polarity to the opposite.

Maintenance guides emphasise that you do not remove all of the mica between segments. You only recess it by roughly a millimetre or so (typical values like 1/32″ to 1/16″ are quoted), just enough to keep it from scraping the carbon brushes and to prevent mica “ridges” from lifting the brushes and causing arcing. The remaining mica still holds the structure together and keeps adjacent bars from shorting.

So in the industrial world, “insulation removal” usually means:

- slightly sinking the insulator below the copper to control mechanical contact and sparking;

- never completely removing the insulating barrier between segments.

In the bench-top motor, “only half the insulation removed” means:

- keeping insulation on half the circumference of one coil end to control the timing of when the circuit closes.

In both cases the theme repeats: you remove just enough insulation to shape the current in time or space, while keeping enough to preserve electrical separation and mechanical integrity.

Why this simple trick still matters when you “know the theory”

If you already know DC machine theory, it is tempting to treat the classroom half-insulated commutator as a toy hack. But it quietly contains several ideas that carry straight into serious design work.

First, it shows that you do not actually need continuous current to get continuous rotation. You need current that is correctly phased with respect to the mechanical angle. Everything else is details of smoothness and efficiency.

Second, it forces you to think about what the motor does when the torque goes to zero. Does your system have enough inertia and low enough friction to coast through the dead band? If not, you need more poles, proper multi-segment commutation, or some kind of feedback control.

Third, it reminds you that any commutator, no matter how elaborate, is really just a repetitive arrangement of three jobs: connect, disconnect, reconnect with reversed polarity. The school motor collapses all of that into one scraped patch of copper.

Once you see the half-insulated wire that way, the original question almost answers itself. Only half the insulation is removed because that is the minimum surgery that still lets the commutator do its job: give the coil current exactly when its magnetic torque would push in the desired direction, and stay out of the way for the rest of the turn.