Why Commutators Are Still Essential in Modern DC Motors

Even with cheap microcontrollers and very polished brushless drives, the mechanical commutator keeps showing up on real BOMs. It stays because it collapses sensing, switching, and protection into a single rotating part that still wins in a few very specific — but economically large — corners of the market.

Table of Contents

The story everybody tells, and what it hides

If you read recent application notes and marketing pages, the script is familiar: brushless DC motors are more efficient, quieter, longer-lasting, and easier to control precisely, so they “replace” brushed machines almost everywhere.

That’s true if you only look at the motor as a component. It becomes less true once you view the whole system: motor, drive, wiring, software, field service, and the very human way products are specified and used in the field.

Under that wider view, the commutator is not a relic. It is a design pattern: local, analog commutation baked into the rotor, almost totally independent of whatever the rest of the product is doing.

You can replace that pattern with silicon and firmware. Many teams should. Some absolutely shouldn’t.

What the commutator really buys you

You already know the formal definition: a rotary switch that reverses current in the armature to keep torque in one direction, acting as a mechanical rectifier in generators.

What matters in 2025 is what that means for design work.

First, commutation happens exactly where the physics demand it: right at the armature, tied tightly to rotor position, with no encoder cables, no Hall sensors, no resolver, no angle-estimation code. Misalignment exists, but it is bounded by the geometry of the brushes and segments, not by sampling jitter or software latency.

Second, current switching is self-synchronizing. As long as brushes are in roughly the right plane, the machine finds a way to start and keep turning. No start-up state machine. No “did we miss the first Hall edge?” bugs. No corner case where a low battery and a cold motor confuse the sensorless estimator.

Third, the commutator pushes a lot of ugly behavior into the rotor, away from your PCB. High di/dt happens under the brushes instead of in your copper pours. That still radiates noise and causes sparking, but it does so in a mechanically constrained zone that has been understood for a century.

This is not elegance. It is containment.

Why brushed motors keep getting specified anyway

Look at sectors where brushed DC motors remain common: power tools, automotive starters, low-cost pumps, toys, some low-end e-mobility drives, simple actuators. Not because nobody has heard of BLDC, but because the full system optimization ended at a different place.

Often the reasoning quietly looks like this:

The overall device is disposable or has a short, clearly bounded life. Brush wear and commutator resurfacing are not concerns because the product will fail somewhere else first.

Unit cost dominates everything. Moving commutation into electronics means adding a controller, gate drivers, more careful layout, and test effort. On paper, the BLDC motor might be only slightly more expensive than the brushed unit; after you cost the electronics and development time, that gap widens again.

The motion profile is brutal, but brief. High starting torque, frequent stalls, battery sags — places where you want copper, iron, and a simple switch, not a finely tuned vector-control drive.

Regulatory and EMC requirements are modest or well understood. You can live with brush noise and sparking, maybe with a simple RC snubber or some suppression components, instead of going through a full redesign of the drive for lower emissions.

So the commutator survives not despite its imperfections but because they line up with the product’s own limitations.

Comparing the two patterns at system level

Here is a compact way to think about commutator-based DC motors versus electronically commutated motors when you look at the entire product, not just the motor catalog page.

| Design dimension | Mechanical commutator (brushed DC) | Electronic commutation (BLDC and similar) |

|---|---|---|

| Commutation location | On the rotor, via copper segments and brushes | In electronics, via transistors and control firmware |

| Position awareness | Implicit: geometry of armature, segments, and brush plane | Explicit: sensors or estimators feeding a controller |

| Startup behavior | Self-starting over wide conditions, limited by brushes and supply | Depends on sensor strategy; may need special startup sequences |

| Bill of materials | Simple motor plus minimal drive; strong cost advantage in low-end gear | Higher part count in electronics; motor can be cheaper per watt |

| Maintenance | Brushes and commutator wear, dust, occasional resurfacing on large machines | Bearings dominate wear; electronics age rather than consumables |

| Efficiency & thermal | Losses in brush contact and commutation; harder to cool armature | Better copper utilization and cooling; often higher efficiency |

| Noise & EMI | Sparking, brush noise, torque ripple intrinsic to design | Quieter, with emissions shaped by drive algorithms |

| Fault tolerance style | Often robust to dirty power and simple overloads; failure can be mechanical and obvious | Can ride through some faults via control, but failure modes may be sudden and opaque |

Notice how the commutator looks worse on many rows but still attractive in one: the very first engineering constraint on most projects, cost, especially for “good enough” motion.

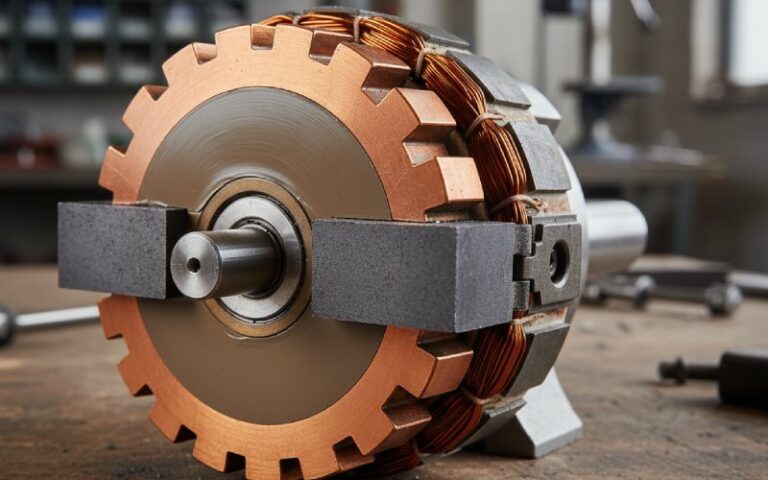

Modern commutators are not museum pieces

It is easy to picture a commutator as a Victorian copper cylinder. Real ones in current production look different.

Manufacturers have pushed the materials: better carbon brush formulations, hybrid metal-graphite mixes, and improved insulators between segments. Large industrial machines still use refillable dovetailed commutators that can be repaired; small motors in consumer equipment use molded, non-repairable commutators that are designed to last exactly as long as the device itself.

Surface treatment, seasoning processes, and balancing have also moved on. Spin seasoning and over-speed testing for traction, aerospace, and similar applications are common where a commutator failure would be more than just inconvenient.

All of this means the commutator you specify today is not a copy of a 1950s drawing. It is a part that has quietly absorbed decades of manufacturing experience and field failures.

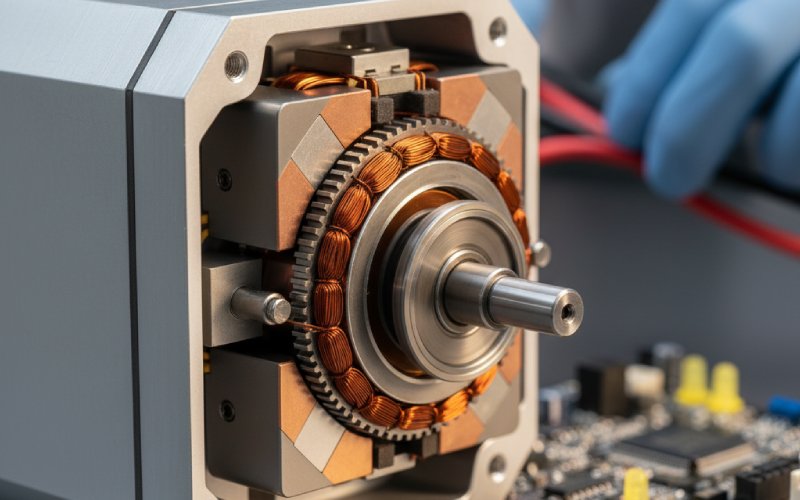

Where electronic commutation correctly dominates

There are also clear spaces where insisting on a commutator is simply mis-engineering.

High-power, high-voltage DC machines do not scale well with mechanical commutators; current density, arcing risk, and brush losses rule them out above a few megawatts. Large machines in power generation and heavy industry have moved decisively toward AC and brushless designs.

Applications with strict EMC limits, very low acoustic noise requirements, or high precision in speed and torque control also lean strongly to BLDC or AC drives. Medical equipment, HVAC systems with tight efficiency regulations, many modern EV platforms, robotics, and automation axes fall into this category.

Here the commutator is not an underdog hero. It is the wrong component.

Practical questions when you are choosing

When your spreadsheet says “DC motor, TBD,” the core question is not brushed versus brushless as an abstract technical debate. It is which commutation pattern matches the rest of the product’s constraints with the least drama.

You can start by asking how long the product truly has to last in real use, not in the brochure. If field data says users upgrade, discard, or mechanically destroy the device after a few hundred hours, commutator wear may never be the limiting factor. If the device will sit in a hospital for ten years, running quietly at all hours, a brushless design aligns with reality.

Next, examine who owns the complexity. A brushed motor pushes complexity into mechanical wear and replacement, tasks that maintenance staff worldwide already understand. A brushless motor pulls that complexity into your PCB and firmware. That is easier to manage at scale in some organizations and much harder in others.

Power supply quality is another filter. If you know your motor will see brownouts, hot-plugging, battery sags, or users who love abusing the on/off switch, a commutator may tolerate those insults more gracefully, even if it does so with more noise and less efficiency.

These are not sentimental reasons. They are about risk, tooling, skills, and the reality of your support organization.

The future role of commutators

Electronic commutation continues to expand. Semiconductor costs drop, integrated motor-control ICs get better, and software libraries hide a lot of complexity. For high-volume, feature-rich products, that path is obvious.

Mechanical commutators, however, are not disappearing; they are retreating into the niches where their odd combination of traits makes sense: low-cost gear, brutal duty cycles, environments where simple field service beats sophisticated diagnostics, and places where motor physics need to be solved locally in copper, not remotely in code.

So when you see a commutator on a new product drawing, it does not necessarily signal conservative thinking. Often it means someone looked at the economics, the maintenance story, the EMC lab schedule, and the organizational skills on hand — and decided that one rotating switch was still the least complicated answer.