What Is a Split Ring Commutator?

A split ring commutator is a segmented copper ring on a rotating shaft that quietly does one job: it flips current direction at just the right times so that a DC motor or generator behaves the way you expect, not the way raw physics would prefer. Everything else is detail and compromise around that one job.

Table of Contents

Quick answer, without the fluff

In a simple DC motor or generator, the armature windings live on a rotor inside a magnetic field. Left alone, the induced currents would naturally alternate. The split ring commutator interrupts that natural behaviour and re-routes the connections every half turn.

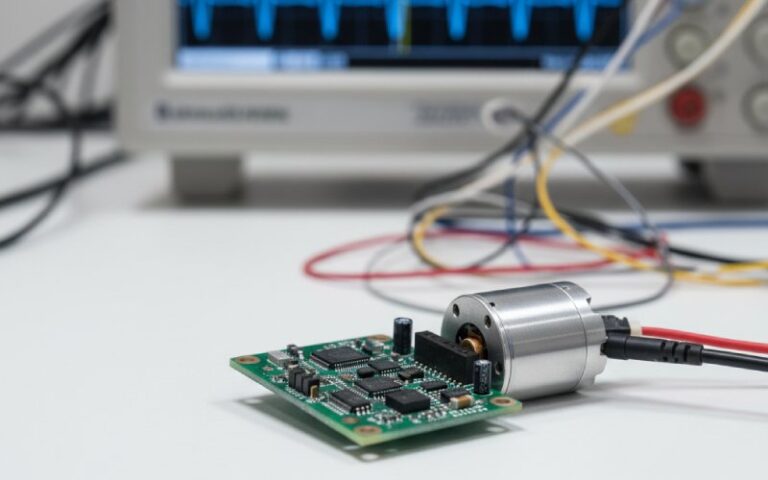

Mechanically, it is a copper ring cut into two insulated halves, mounted on the shaft, with carbon brushes pressing on the outer surface. As the rotor turns, each brush slides from one half to the other. Electrically, that sliding action swaps which side of the coil is connected to which supply terminal. The field stays the same, the current in the conductors keeps getting flipped, and the torque on the rotor keeps pointing roughly in one direction instead of fighting itself.

That is the core idea. Most of the interesting engineering is about making this crude mechanical switch survive heat, vibration, high current, exam questions, and occasionally neglect.

How it actually lives inside a motor

On drawings, the commutator looks like a neat pair of semicircles. On an actual machine it is a cylindrical stack of copper segments, separated by thin wedges of mica or another insulating material, shrunk or pressed onto the shaft. The “split ring” in textbook motors is just the two-segment extreme of the same idea.

Each segment is hard-connected to an armature coil. The carbon brushes, held in spring-loaded holders, press against the cylindrical surface. When the rotor spins, the brushes see a sequence of segments. Timing is everything here: the transition between segments is arranged to occur as the coil passes through the magnetic neutral zone, when the induced voltage in that particular coil is minimal. This reduces sparking and heating at the brush–commutator interface.

In real machines, that “neutral” position can drift with load, brush wear, and manufacturing tolerances. So the design often includes a way to shift brush position a little. Not elegant, but it works. You end up with a mechanical compromise between maximum torque, acceptable commutation, brush life, and noise.

Split ring vs slip ring: not just a vocabulary test

A lot of online explanations stop at “split ring for DC, slip ring for AC.” Technically true, but it hides the tradeoffs that actually matter when you are choosing hardware or trying to debug a motor.

Here is a compact comparison.

| Aspect | Split Ring Commutator | Slip Ring |

| Structure | Copper ring cut into two or more insulated segments, usually with mica between segments | One or more continuous conductive rings with no intentional gaps |

| Main role | Periodically reverses current in rotor windings, acting as a mechanical rectifier | Provides continuous electrical connection between stationary and rotating parts |

| Typical machines | DC motors and DC generators, small brushed DC drives, teaching rigs | AC generators, wound-rotor induction motors, signal and power transfer in rotating platforms |

| Current behaviour at brushes | Output can be made effectively unidirectional even though the rotor sees alternating currents | Current at brushes follows the actual waveform in the rotating circuit (often AC) |

| Maintenance pattern | Sensitive to brush seating, segment wear, undercut depth, and arcing | More tolerant, usually less sparking, but still brush and ring wear over time |

So when you say “split ring commutator,” you are really talking about a slip-ring-like interface that has been deliberately broken and re-wired so that mechanical motion reshapes the circuit.

Why the ring is split at all

Imagine replacing the split ring in a DC motor with a pair of smooth slip rings that never swap connections. The rotor sits in a fixed magnetic field. Current direction in each conductor stays tied to one brush. The torque flips direction every half turn. You get a twitch, maybe a half rotation due to inertia, and then the system tries to settle into a reluctant equilibrium where forces prefer to hold the rotor, not keep it spinning.

The split ring changes that story. Each time the coil crosses the neutral position, the brush leaves one segment and lands on the other. Now the conductor that was previously “left to right” relative to the field becomes “right to left” in current while its physical orientation has also swapped. Two sign changes cancel, so the torque direction stays roughly consistent.

In a DC generator, the same trick works in reverse. The armature windings see an alternating induced voltage as they spin through the field. The commutator swaps which coil side connects to which output terminal just as the induced EMF would have changed sign. So the external circuit sees a pulsating direct voltage instead of a clean sine wave that keeps changing polarity.

In both cases, the split is not ornamental. It is the mechanical stand-in for an H-bridge or rectifier.

Design variables that actually matter

Real commutators rarely stop at two segments. As you add more armature coils, you add more segments. This spreads the current and reduces ripple in torque or output voltage. The two-segment split ring that appears in school diagrams is just the simplest case. In industrial DC machines, the “ring” becomes a many-bar assembly, but the logic stays the same: conductors that need to swap connections do so as they cross the neutral zone.

Brush material sits at the centre of the reliability equation. Graphite and carbon-graphite brushes are soft enough to conform to the commutator surface, conducting while also lubricating. They wear instead of the copper, which is usually what you want. Pick them too soft and they vanish quickly and create dust. Too hard and they gouge the segments.

Brush pressure is another knob. Too light and contact becomes intermittent, causing sparking and heating. Too heavy and mechanical wear accelerates and the commutator runs hotter from friction. On large machines this can be tuned with spring arrangements; on small hobby motors it is baked into cheap stamped parts, which is why they can sound harsh and wear out in odd ways.

Insulation between segments is not just “there or not.” The mica is usually undercut slightly below the copper surface so that brushes ride only on metal, not on the harder insulating material. If the mica rises due to uneven wear or poor manufacturing, the brushes bounce more, arcs form more easily, and commutation worsens.

Real-world problems: wear, sparking, and failure modes

From a maintenance viewpoint, the split ring commutator is both clever and vulnerable. Every reversal happens through sliding contact at the brushes. That means metal, carbon, heat, and arcing in the same small region.

High current or poor timing gives visible sparking at the brush face. That erodes copper from some segments and deposits it on others, producing dark stripes, uneven bars, and a rough surface. Once the surface loses its slight cylindrical smoothness, brushes stop bedding properly. Contact area shrinks, local current density rises, and the cycle accelerates.

At the same time, contaminants and brush dust can build conductive tracks in the insulating gaps. Then you get partial shorts between segments. The motor still runs, just poorly, drawing more current, running hotter, and producing a sound that has more hiss than usual. Technicians sometimes skim the commutator, re-true the cylinder, undercut the mica again, and run in new brushes to restore reasonable operation.

For small disposable motors, none of this happens. The unit just seems weak one day, then fails and gets replaced. It is still the same commutator physics, just with no maintenance loop in the story.

Where you still see split ring commutators

Textbooks love the simple rectangular coil in a uniform field. Real devices are less tidy but not exotic. Split ring commutators show up in:

Small brushed DC motors in toys, fans, hand tools, and automotive actuators. Teaching rigs and lab benches where the current needs to look “DC” on a meter even though the rotor windings are not. Legacy DC drives for hoists, rolling mills, and traction systems that have not yet been switched to solid-state solutions.

In many new designs, the role of the split ring has migrated into electronics. Brushless DC motors and stepper motors rely on semiconductor switches and rotor position sensing instead of physical commutation. The underlying requirement is the same: current in the conductors must be in the “right” direction relative to the magnetic field. The difference is that the device doing the switching is no longer a pair of copper segments passing under a carbon brush.

How to think about it in exams and in design reviews

When you need a one-line definition, you can treat the split ring commutator as a rotating switch on the rotor of a DC machine that reverses connections every half turn so that torque or output voltage stays one-sided instead of alternating. Any marking scheme or data sheet is usually satisfied with that.

For deeper reasoning, imagine the commutator plus brushes as a physical H-bridge glued onto the rotor. The geometry of the segments encodes the switching pattern. The magnet and armature just respond to whichever conductors end up with current at any instant. This mental model makes questions about “what happens if you replace it with slip rings?” or “why does brush shift matter?” almost routine: you are just asking when and how the connections swap.

Final notes

A split ring commutator is simple enough to sketch on a napkin, but subtle once you care about efficiency, lifetime, noise, or electromagnetic performance. The cut in the ring, the exact position of the brushes, the texture of the copper, and the properties of the carbon decide whether that small rotating switch behaves like a quiet rectifier inside a dependable motor or like a short-lived spark machine hiding behind a plastic housing. The physics is basic; the engineering is where most of the interest actually sits.