What Is A Slip Ring Commutator?

A slip ring commutator is a rotating electrical interface that combines two ideas on one shaft: continuous rings that simply pass power or signals across a moving joint, and segmented copper bars that deliberately switch or reverse current. People argue about the term, but in real machines it usually means “the brush assembly that gives me both continuous feed and controlled switching on a rotating member, in one lump of copper and insulation.”

Table of Contents

Why the term is so messy

If you read textbooks and vendor blogs side by side, you will notice the terminology drift.

Slip rings are described as electromechanical devices that move power, data, or signals from a stationary structure to a rotating one, without twisting cables and while allowing unlimited rotation. They rely on continuous conductive rings and sliding brushes and do not try to reshape the waveform; they just carry it across.

Commutators, on the other hand, show up in DC motors and generators as segmented copper cylinders. Their job is to reverse current in the rotor windings every half turn (motor case) or to mechanically rectify the internal alternating voltage into a unidirectional output (generator case).

Then you open a manufacturer page and see “slip ring commutator assemblies,” or “commutator rings,” or even a blog post literally titled “Slip Ring Commutator” that treats the whole rotating copper package as one concept.

So the phrase often ends up meaning one of three things, depending on who is talking.

First, some people use “slip ring commutator” loosely for any brush-type rotating electrical connector, regardless of whether it actually switches current. Second, in DC machines, they may use it for the commutator itself, because it is made of rings sliced into bars and it does slip under brushes. Third, in more complex machines and industrial gear, the phrase can refer to a hybrid assembly that literally contains both continuous slip rings and a commutator section on the same shaft.

The only way to know which meaning is active is to look at the electrical job it is doing in the circuit, not just the words.

Short functional picture

If you ignore naming for a moment and just think in terms of function, the pattern is clearer.

A pure slip ring assembly gives the rotor whatever waveform you already have outside. AC in, AC out. Digital signals in, the same digital signals out. It does not rectify, modulate, or chop the current. It is simply a rotating terminal block with contact physics behind it.

A pure commutator acts like a mechanical switch array. In a DC motor, it keeps the torque mostly in one direction by reversing current in each armature coil as that coil passes through the neutral zone of the stator field. In a DC generator, it converts the alternating internal voltage into something that looks like DC at the terminals.

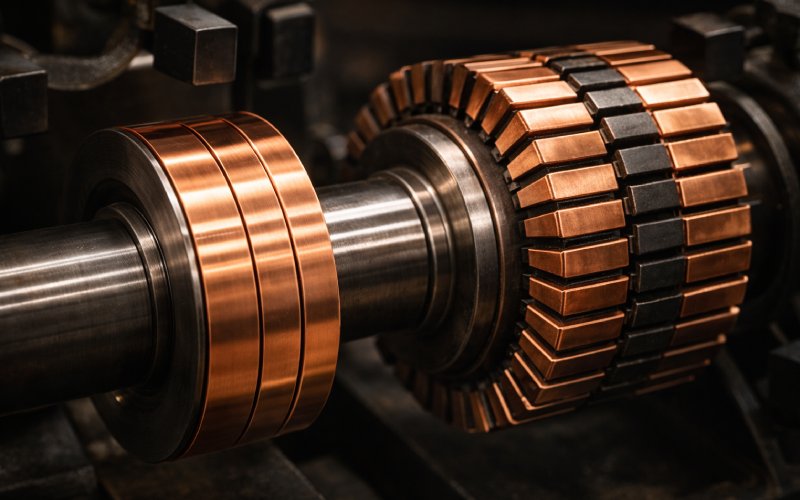

A slip ring commutator, in the more careful sense, is an assembly that does at least one of these functions plus provides through-connection for other circuits. You see continuous rings feeding excitation or signals, and segmented bars driving or sampling armature coils, all in one mechanical module. The brushes sit over both regions, some doing “just pass it through,” others doing “switch it at the right angle.”

Same shaft. Same bearing set. Mixed behavior.

Quick comparison in one table

The contrast is easier to hold in your head when you stack it side by side. This table uses “Slip ring commutator” in the hybrid sense: an assembly that actually includes both continuous rings and segmented commutator bars.

| Aspect | Slip Ring | Commutator | Slip Ring Commutator (Hybrid Assembly) |

| Primary job | It provides continuous electrical connection between stationary and rotating parts without changing the waveform. | It periodically reverses or rectifies current between rotor windings and the external circuit. | It combines continuous transmission for some circuits with controlled switching for others in one rotating unit. |

| Physical geometry | It uses one or more continuous rings with smooth circumferential surfaces. | It uses many insulated copper segments arranged around a cylinder or disk. | It places smooth rings and segmented bars on the same shaft or in one housing, often in adjacent axial sections. |

| External circuit view | The outside sees almost exactly the same voltage and current waveforms as if there were a flexible cable instead of the rotating joint. | The outside sees a largely unidirectional DC output or input, even though the rotor windings themselves experience an alternating current. | Some external terminals see “simple pass-through” behavior, while others see switched or rectified behavior from the commutated part. |

| Typical machine examples | AC generators with separate excitation, wind turbines, medical imaging gantries, rotating antennas, industrial slip-ring motors. | DC motors, DC generators, universal motors in tools and appliances, older traction drives. | Specialized generators, test rigs, machines needing both DC armature circuits and additional rotating services like sensors, heaters, or field supplies on the same shaft. |

| Key design worry | Contact resistance, signal integrity, and wear under continuous rotation. | Commutation quality, sparking control, and segment insulation under switching stress. | Mechanical integration of both functions, brush layout, thermal management, and cross-talk between the “plain” rings and the switched segments. |

| When a vendor says it | They usually mean a standard slip ring product family, especially in automation or wind. | They often mean classic DC machine hardware, sometimes called “commutator rings.” | They often mean a custom or semi-custom module providing both slip rings and commutator in one assembly. |

This is not universal. But it matches what you will see across technical notes and modern product pages.

Anatomy, once, without over-teaching it

You already know the basic parts: rotor, stator, rings or segments, brushes, insulation, end bells. No need to walk slowly through that.

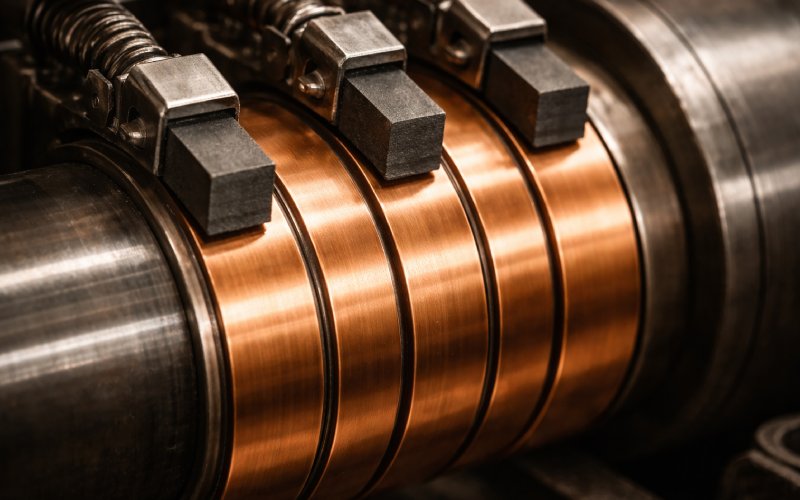

The interesting part is how the copper is cut and grouped. In a slip ring, each ring is one circuit. You might have a power ring, a return ring, a CAN bus pair, a fiber channel path aided by an optical rotary joint nearby. The brushes map cleanly onto them, with one or more brush per ring, often doubled up for redundancy or current capacity.

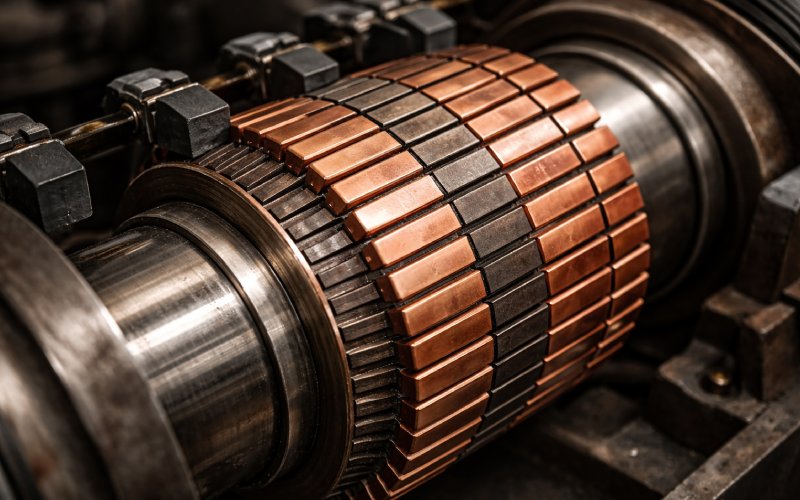

In a commutator, the copper is sliced into many segments, each tied into a coil group. The brush width spans more than one segment so that it never loses contact, and the geometry ensures that the current in a given coil changes direction around the moment it crosses the magnetic neutral axis. The physical slotting is not decoration; it encodes the winding scheme itself.

In a slip ring commutator assembly, you simply get both of these geometries in one place. You may have a set of continuous rings close to the bearing and a commutator stack closer to the active part of the rotor. Or the other way around, depending on ease of maintenance and stray field concerns. The brushes and holders then have to coexist, with different contact pressures, materials, and cabling styles occupying the same cramped end housing.

Mechanically it is still just copper, insulation, steel, and carbon, spinning. Electrically it is two different behaviors hiding in one casting.

Where you actually see them

You rarely see the phrase “slip ring commutator” stamped on a datasheet for mass-market gear. What you see instead is the outcome of the design decision.

In wind turbines, the “slip ring” discussion is mostly about how to get power and signals to blade pitch actuators and sensors while the nacelle and hub rotate freely. Contact technology, corrosion, temperature swings, and long service intervals dominate that conversation.

In older DC traction drives or heavy DC cranes, the “commutator” discussion is about current density, arcing, brush dust, and the maintenance schedule. The assembly is large, loud, and very visible.

Hybrid slip ring commutator assemblies appear in more niche roles. Think of test machines where you need DC excitation of a rotor, high-current armature circuits, and at the same time a handful of high-speed signal channels on the same spinning element. Or generator shafts where designers chose to run both rectified outputs and auxiliary services through one integrated unit instead of splitting it into two separate interfaces.

From the outside, plant technicians usually call the whole end assembly “the slip ring” or “the commutator” regardless. Naming discipline fades under real-world time pressure, but the underlying physics does not.

What really matters in design, beyond the label

The difference between a decent slip ring commutator assembly and a bad one is almost never about the textbook definition. It is about all the quiet, unglamorous trade-offs the designer made.

First, contact material choices. Silver-graphite, copper-graphite, pure graphite, or precious metal systems each lean toward certain current densities, speeds, and signal qualities. A hybrid assembly might even mix brush grades: relatively soft, low-noise brushes for the signal rings, and more robust, higher-friction brushes for the commutator part that has to carry armature current and tolerate switching.

Second, contact pressure and surface speed. Too little pressure and you get sporadic contact, micro-arcs, and ugly noise on sensors. Too much and you grind the rings down quickly, generate heat, and load the bearings. Surface speed increases wear and affects how lubrication films form or fail. A hybrid unit usually has the same shaft speed across both regions, but the acceptable pressure window is not the same for all the circuits sharing that shaft.

Third, environment. Moisture, dust, vibration, and chemical vapors rewrite all the material tables. The wind turbine design articles are full of very practical notes on sealing, purge systems, and choice of contact technology specifically to deal with salt fog, ice, and long idle periods.

Fourth, maintenance philosophy. Some assemblies are sized and mounted so that a technician can change brushes in an hour with basic tools. Others are buried deep inside a machine, effectively making the assembly “lifetime” hardware, so designers oversize everything and bias toward conservative current densities and benign contact chemistry.

None of these care that much about whether you insist on calling it “a slip ring,” “a commutator,” or “a slip ring commutator.” But all of them dictate whether your machine stays online.

Failure patterns and what they hint at

When a slip ring commutator assembly ages, it leaves clues. Engineers who spend years with these machines read those clues the way power-electronics people read oscilloscope traces.

A dark, uniform band of wear on the slip rings, with relatively clean brush faces and low dust, usually indicates that contact pressure, alignment, and material pairing are in the right zone. Sudden streaks, localized overheating, and patchy deposits suggest vibration, misalignment, or contamination. If only certain rings show this, you can map the problem back to specific circuits or loads.

At the commutator part, you see banding, grooving, and “bar burning” where individual segments overheat due to uneven current sharing or poor commutation timing. The brush face pattern reflects that, with chipped or glazed spots rather than smooth matte contact surfaces. Adjusting brush position relative to the neutral plane, changing brush grade, or tweaking the armature winding details are common response patterns there.

In a hybrid assembly, the two regions talk to each other indirectly. Excess heat from poor commutation can elevate ring temperatures and accelerate wear on the “plain” slip-ring circuits. On the other side, a dirty or leaky slip-ring compartment can feed conductive dust or moisture toward the commutator, raising the risk of tracking and flashover. So when you see one side misbehaving, the other side deserves inspection too, even if its own measurements still look fine.

Selecting or specifying one without getting lost in wording

If you have to choose or specify a slip ring commutator for a project, the safest way is to forget the label for a moment and write down two separate things.

First, specify all circuits that must cross the rotating interface. For each, capture voltage range, current, waveform type, frequency or data rate, isolation needs, and any special shielding or noise constraints. Power to a motor winding, Ethernet, resolver signals, thermocouple lines, DC excitation, low-level analog sensing: each of these likes a different treatment in copper and carbon.

Second, specify what the interface must actually do to those circuits. Some circuits just need continuous path continuity. Others must be switched or rectified in a very controlled way, synchronized with rotor angle or magnetic field position. That second group is where the commutator behavior appears by design, not by accident.

Once you hand this description to a vendor, they will usually map it to one of three answers. They might solve it with a standard slip ring plus external electronics and no mechanical commutator at all. They might solve it with a classic commutated DC machine where no additional rotating circuits are needed. Or they might propose the hybrid “slip ring commutator” assembly you were asking about, integrating both behaviors into a single mechanical unit.

The last option tends to show up when shaft count, space, or mechanical complexity rule out separate interfaces.

Short wrap-up

So, what is a slip ring commutator, really? It is not a mystical third category of hardware. It is either a loose name for any brush-type rotating connector, or more helpfully, a hybrid assembly that provides both continuous slip-ring style connections and commutated switching on the same rotating structure.

Slip rings move energy and information across a rotating boundary without changing its shape. Commutators intentionally reshape current with segmented copper and timed contact. A slip ring commutator is simply where those two needs collide in the same machine, and the designer decides to solve them with one rotating assembly instead of two.

The terminology may drift, but if you keep your eye on what the external circuit sees, the picture stays stable.