What Is a Commutator Skimmer?

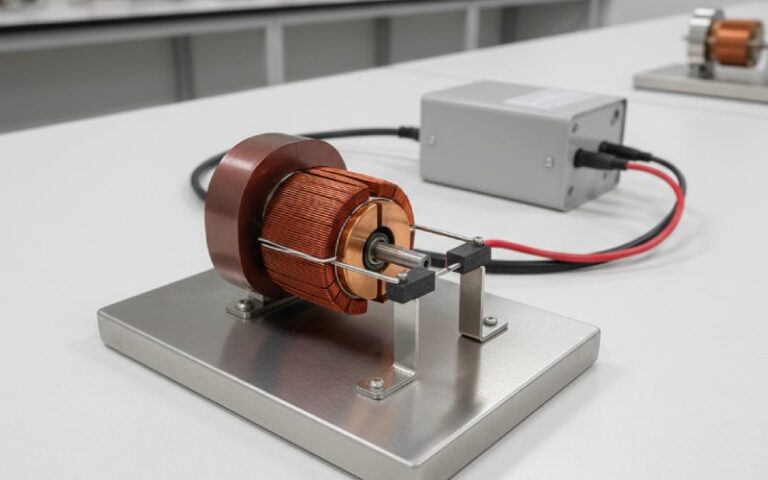

A commutator skimmer is a machine or setup that very precisely re-cuts the working surface of a DC motor commutator so brushes run quietly, current transfers cleanly, and the armature is worth keeping instead of scrapping. That is the short version, and for most maintenance reports, it is enough.

Table of Contents

The quick definition that actually matches workshop reality

In day-to-day shop language, people use “commutator skimming” in two ways. Sometimes they mean the process: mounting an armature, taking very light cuts across the commutator surface, and restoring concentric, smooth copper ready for undercutting and dressing. Sometimes they mean the machine itself: an armature turning lathe built specifically for commutators, marketed as a “commutator skimmer” or “commutator skimmer and finishing lathe.”

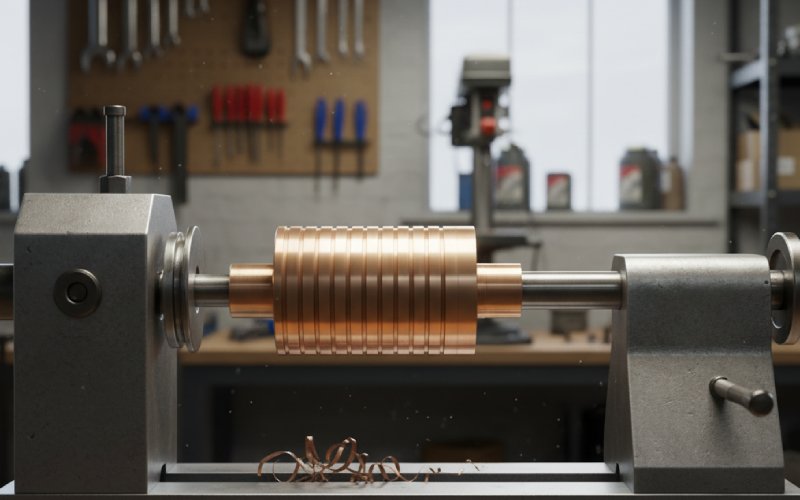

So a commutator skimmer, in the strict equipment sense, is a dedicated turning machine designed around armatures. It grips the shaft between centres or in chucks, drives the rotor, and feeds a cutting tool along the commutator to remove a thin outer layer of copper, often in the order of 0.02–0.2 mm per pass, with surface finishes around a few tenths of a micron when set up correctly.

In the broader maintenance sense, when a service sheet says “commutator skimming,” it usually bundles three actions together: turning the commutator, undercutting the mica, and then finishing or chamfering so the brushes bed in without tearing. Many repair shops and OEM-approved procedures treat those steps as a single maintenance operation, just with internal sub-steps.

You already know what the commutator does electrically. The skimmer does not care about that. It only cares about geometry, surface condition, and how long you can keep that armature in productive use.

Why skimming exists at all

If commutators stayed perfectly round, nothing would be skimmed. They do not. Thermal cycles, brush wear, contamination, vibration, all chew away at bars in an uneven way. The result is out-of-round surfaces, high and low bars, ridges, burn marks, and localised blackening where commutation has gone bad.

At some point, polishing with stones or garnet paper stops being sensible. Maintenance guides state this plainly: if the surface is too rough, eccentric, or badly grooved, you move from “clean and dress” to “turn the commutator,” with quite conservative limits on surface speed and cut depth.

Skimming is the controlled version of that turning. Light cuts. Known tool geometry. Measured diameter before and after. The goal is simple: restore a true cylinder on the commutator that is concentric with the shaft and uniform enough that brushes ride steadily, without trying to correct every minor cosmetic flaw.

How a commutator skimmer actually works

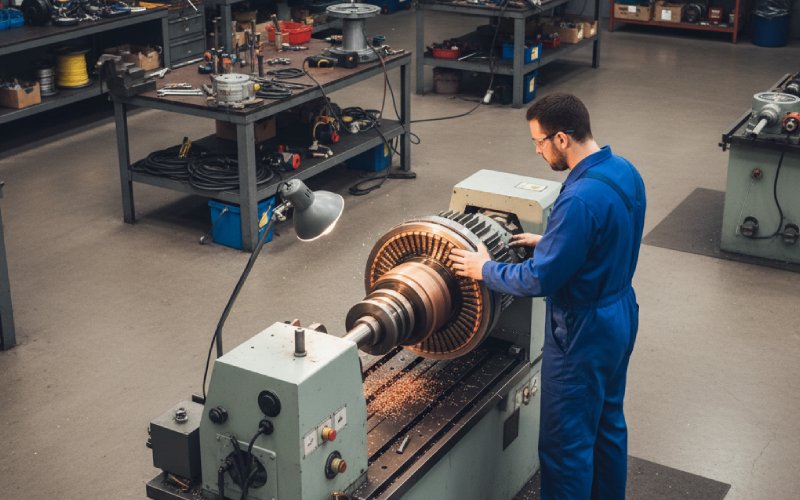

Most commercial commutator skimmers look like compact lathes built around armatures. An operator loads the rotor between centres or into fixtures, clamps it, and the machine’s drive rotates the armature. A cutting head, usually servo-fed, traverses along the commutator while removing a thin layer of copper. Feed and speed are often programmable; belt or servo drives keep surface speed in a safe band while avoiding chatter.

The cutter may be carbide or diamond tipped, depending on the class of machine and finish required. High-end skimmers quote typical roughness values around 0.25 µm on commutators and tight concentricity limits, often within a few microns, which is far better than what a general-purpose engine lathe routinely delivers with improvised setups.

Control is often via a small PLC. Nothing mystical: set armature length range, commutator length, speed, and depth of cut, let the cycle run, then unload manually. Automation is focused on repeatability and shorter cycle times, not on making the machine look clever.

You can perform skimming on a normal lathe, and many small shops still do, but that is a different level of risk for chatter, setup error, and geometry drift. The dedicated skimmer just removes variables that cause callbacks.

Where skimming sits in the DC motor repair workflow

Training material for motor electricians usually lists commutator skimming alongside undercutting and slip-ring work as standard machining operations within an overhaul.

In a typical DC motor rebuild on an armature that is worth keeping, you would see a sequence similar to this, though practices vary. First, inspection and testing: measuring insulation resistance, checking commutation marks, looking for pattern issues on the bars, and verifying shaft run-out.

Then comes armature restoration. If tests justify it, the commutator is skimmed. The armature is dynamically balanced. Any field rewinding or connection repair is carried out, and the commutator is undercut and chamfered after machining. Commercial repair brochures and service descriptions repeatedly pair “commutator skimming and undercutting” as a coupled service, because that is how it is actually sold and delivered.

Finally, brushes are fitted, pre-bedded where procedures call for it, and run-in on test bays. Guidance from older military and industrial documents stresses the link between post-skimming brush bedding and commutator life, which is easy to forget when you focus only on machine capability.

The commutator skimmer is in the middle of all that, not at the start and not at the very end. It is the geometry reset, nothing more and nothing less.

Skimmer vs other methods: what you are really choosing

Here is a compact way to think about a commutator skimmer compared with other ways of rescuing a commutator or avoiding the job entirely.

| Option | What it physically does | When it makes sense | Typical limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dedicated commutator skimmer (automatic or semi-automatic) | Holds the armature in a controlled fixture, turns the commutator at a set surface speed, and removes a uniform, small layer of copper in one or more passes, usually followed by separate undercutting. | Best fit for regular DC motor repair work, where you see enough volume to justify the fixture and you care about predictable finish and minimal metal removal over many cycles. | Capital cost, operator training, and the temptation to skim too often because the machine is sitting there. You also remain constrained by manufacturer minimum-diameter limits. |

| General-purpose lathe plus manual tooling | Uses a standard lathe to rotate the armature while an improvised cutting tool or boring bar is applied. Typical in small workshops and hobby settings. | Works for one-off or low-value motors where the economics do not justify specialist equipment, or for emergency work where a skimmer is not available. | Setup errors, less control over run-out, and a higher risk of surface chatter or non-concentric cuts. Much more dependent on individual skill. |

| Hand dressing, stones, and brush-based cleaning | Uses commutator stones, specialized brush materials, or garnet paper to clean and smooth a surface without cutting new geometry. | Suitable when the commutator is still geometrically sound but contaminated, lightly scored, or has poor film. Good for in-situ work where machining is impractical. | Cannot fix serious eccentricity, deep grooving, or high bars. Overuse of the wrong abrasives can make things worse. |

| Replace or scrap the armature | Throws the problem away and installs a new or fully rebuilt armature or motor. Common in standard-frame low-cost machines. | Logical when the commutator is already near minimum diameter, when there is heavy bar damage, or when labour cost exceeds replacement cost. | Waste of remaining life if you misjudge the condition, and often long lead times for special machines. |

The table is simplified. Real decisions also depend on downtime cost, access to balancing, and whether the asset is critical or just another small drive hidden in a plant corner.

Design features that matter more than brochure phrases

If you compare catalog pages for commutator skimmers, you will see a familiar checklist: specified armature diameter range, shaft length range, maximum cutting length, cutter speed, quoted surface roughness, and concentricity figures.

The important pieces are quieter than the marketing text. One is rigidity. A skimmer with a solid bed, well-aligned centres, and a stable tailstock will give you consistent results across different armatures. Another is control of vibration: some designs use servo and pneumatic systems to keep feed smooth and belt pressure consistent so the cutting force stays predictable instead of varying with every defect on the surface.

Integration with undercutting matters as well. Many shops pair a skimmer with a separate undercutting machine that mills the mica insulation between bars, sometimes using dedicated bench-mounted undercutters with precise positioning. The commutator skimmer sets the geometry; the undercutter restores the slot depth and profile so brushes do not ride on mica that has become proud after turning.

On higher power machines, in-situ skimming on installed units appears in service offerings too. Portable rigs clamp around large commutators and machine them without removing the rotor from the machine, which can cut downtime dramatically for big DC drives or slip-ring rotors.

So, when you evaluate a skimmer, you are really asking three questions. How stiff is the setup. How consistent is the feed and speed control. How well does it sit inside your existing undercutting and balancing process.

What good skimming actually looks like on the commutator

Maintenance documents are surprisingly consistent about what counts as quality in commutator machining. They recommend low cutting speeds, light depths of cut, and avoiding axial movement of the commutator relative to the armature during turning.

After skimming, the mica is undercut back to a modest depth, often around a millimetre or so depending on commutator size, with careful removal of copper particles between the bars. Both workshop guidance and hands-on machinist notes emphasise this cleanup step, because stray copper in the slots is a fast route to renewed arcing.

The surface finish should be smooth and even, but not polished into a mirror with abrasive that leaves conductive residue. Industry guidance warns specifically against aluminium-oxide emery cloth on commutators and slip rings, steering users instead towards stones, garnet paper, or brush-based cleaning solutions that avoid embedding conductive grit.

Well-machined commutators end up with a uniform copper colour that will quickly form the familiar chocolate-coloured film once brushes run at load. That film is not dirt; it is part of normal operation and should not be stripped away every time you see it.

So good skimming is not only about the cut. It is about respecting the minimum diameter, not chasing cosmetic perfection, and letting the machine develop its own stable film again.

Practical rules of thumb, written as straight talk

If your inspection shows deep grooves, heavy ridging, or eccentricity and the commutator is still comfortably above the manufacturer’s minimum diameter, skimming is usually worth considering before you think about replacement. Skipping machining and relying only on stones in those conditions often pushes problems downstream into brush wear and erratic commutation.

If you are already near the minimum diameter, skimming becomes a last-resort salvage method, not routine maintenance. One more cut buys you some running hours but may also be the final use of that armature; planning needs to reflect that instead of assuming endless refurbishment.

If your shop sees only the occasional small DC motor, a dedicated commutator skimmer is probably overkill. A competent machinist with a good engine lathe, the right tooling, and patience can get serviceable results, though it will take longer and depend heavily on their skill.

If you are running a rewind and repair facility handling multiple DC motors, slip-ring machines, or large drives, the economics change. Many such shops bring skimming and undercutting fully in-house, both to control quality and to avoid shipping delays, and advertise that capability explicitly as part of their value.

Those are generalisations, of course. But they map closely to what service providers, training materials, and OEM-related documents describe as normal practice.

When a commutator skimmer is the wrong answer

Sometimes the commutator skimmer is the wrong tool even if you own one. If the shaft is badly bent, the core is damaged, or bars are mechanically loose, you are treating symptoms instead of cause by machining the surface. You can get a clean cut and still have a motor that will not run satisfactorily.

If the asset is safety critical, buried in a lift system or essential production line, documents from owners and insurers often push you towards full overhaul or replacement once commutator condition crosses certain thresholds. You see this in tender specifications that list commutator skimming and undercutting explicitly as part of broader repair and maintenance packages rather than as isolated work items.

Even with a perfect skimmer, the decision is still an engineering trade-off: residual life, downtime, spare availability, and risk tolerance. The machine only cuts copper. It does not answer those questions for you.

A compact answer for spec sheets and reports

If you need a one-sentence definition for documentation, you can safely write something like this: a commutator skimmer is specialised machinery used to machine and restore the working surface of DC motor commutators, typically as part of a combined skimming, undercutting, and dressing operation during overhaul. That line aligns with how service providers, training syllabi, and equipment catalogs use the term.

Behind that neat sentence sits the real story: the decision to keep or replace an armature, the physics of commutation quality, the economics of downtime, and the geometry discipline that a commutator skimmer helps you maintain. You know the theory already. The skimmer is just the tool that enforces it on the copper.