What Is a Commutator in a DC Motor?

A commutator is the part that decides whether your DC motor is useful or just a heater with bearings. It keeps the torque pointed in one practical direction, manages current in the armature, and quietly limits how far you can push speed, power, and reliability before things burn, chatter or stall. Everything else is details.

Table of Contents

The short answer engineers actually use

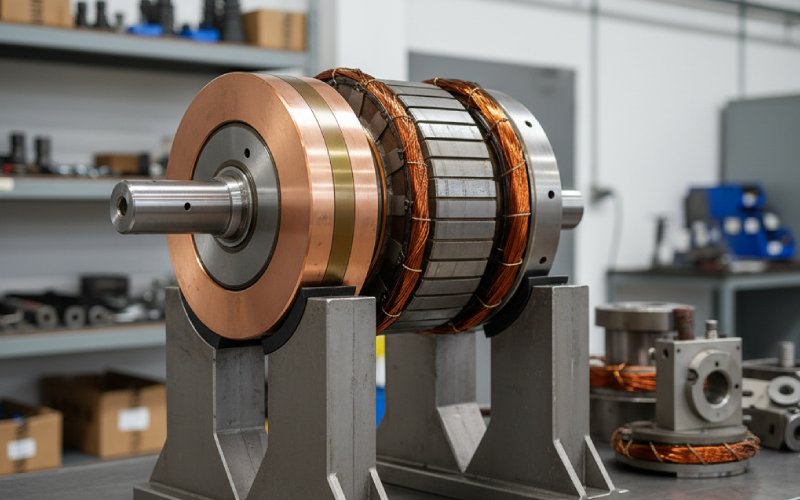

Formally, the commutator is a segmented copper cylinder mounted on the rotor, connected to the armature coils and contacted by carbon brushes. It periodically reverses the current in each coil so that the electromagnetic torque stays in roughly the same direction while the rotor spins.

That’s the line you give in documentation. But in practice you treat it less as “a switch” and more as a constraint engine: it sets the allowable current density, the noise profile, brush material options, and how angry the maintenance team will be after six months of real duty.

You already know the schematic. What matters here is how the commutator behaves when the motor is hot, loaded, misaligned, a bit dirty, and powered from something less ideal than the textbook DC source.

Not just reversing current: shaping torque in time

In the ideal diagram, commutation happens at the instant a coil’s induced voltage crosses zero, so you reverse current with no stress. Real machines miss that perfect instant. Field distortion, inductance and mechanical tolerances all push the current zero-crossing away from the geometric neutral plane.

The commutator lives in that mismatch. Every bar and every brush contributes to how gently or violently the current is forced to change. Wide brushes short two segments for longer, so the transition is spread in time. Narrow brushes shorten that interval and raise the di/dt. More segments mean smaller voltage per segment, which softens the switching but adds manufacturing complexity and more places for faults.

Engineers talk about “good” commutation as if it were obvious, but it is really an optimization: you’re balancing torque ripple, sparking, acoustic noise, allowable brush grade, and cost. Smooth torque often means you’ve accepted more copper and tighter tolerances than the purchasing team wanted.

Geometry and materials: the quiet trade-offs on the rotor

Most references stop after saying “copper segments separated by mica insulation.” The interesting part is why this hasn’t changed much despite decades of materials science. The commutator has to be conductive, hard enough to resist grooving, soft enough to bed with carbon brushes, and stable under high g-forces and thermal cycling.

Mica or similar insulation has a job that looks simple but isn’t. It must avoid tracking, survive repeated arcing events, and keep its mechanical integrity when the rotor experiences centrifugal forces at high speed. Undercutting the mica slightly below the bar surface is one of those odd practices that feels like folklore until you see what happens if you don’t: the brushes ride on a mixed copper–mica surface, contact becomes inconsistent, and commutation worsens.

On the brush side, the carbon mix and density control the compromise between wear, contact drop, and film formation. Pure graphite grades behave differently from copper-graphite blends; some promote a stable low-resistance film on the commutator, others erode it more quickly.

You can look at the rotor and see just a shiny segmented ring. But what you really have is a negotiated truce between mechanical strength, tribology, and transient electromagnetic behavior.

When ideal commutation breaks: armature reaction and its friends

Once you push beyond small teaching motors, armature reaction stops being an exam question and becomes a reliability issue. The armature current produces its own field, distorting the main pole field, so the point where the coil EMF crosses zero shifts away from the geometric neutral.

Now the commutator is switching current in coils that are not magnetically “neutral.” That is where sparking, bar burning, and uneven brush wear start.

A few classic tools show up here:

Brush lead. You physically shift the brushes in the direction of rotation (for a motor) so mechanical commutation lines up with the distorted magnetic neutral. It works, but only at one load point. Change the current, the distortion changes, and your careful brush setting drifts away from optimal.

Interpoles (commutating poles). Small auxiliary poles in series with the armature are placed so that they induce a voltage exactly opposing the coil’s self-inductance during commutation. Done well, they make the process much less fussy with load. Done poorly, they create their own problems.

Resistance and EMF commutation techniques are basically two ways of saying the same thing: either you increase circuit resistance temporarily, or you inject a compensating EMF, to force current to reverse fast enough without large voltage spikes.

So the commutator is not operating against a static field. It is swimming in a field that the armature itself is distorting, and your design choices decide whether that distortion helps or hurts.

Reading the commutator like a log file

You can tell a lot about a DC motor just by looking at its commutator under decent light. Field engineers do this long before anyone opens an oscilloscope case. Patterns on the bars are a physical log of what the current and brushes have been doing.

Here is a practical summary you can keep in the back of your mind:

| Observed commutator / brush condition | Likely electrical or mechanical story | Motor behavior you tend to see | Typical engineering reaction |

| The commutator surface shows a smooth, uniform, slightly brown film with very fine circumferential marks, and brush faces are evenly worn. | Current density is within design limits, brush grade is appropriate, and the supply is reasonably clean, so commutation is happening close to the intended neutral plane. | Torque ripple is moderate, acoustic noise is acceptable, and the unit runs for long periods without attention. | You mostly leave it alone, perhaps log the pattern as a reference image for the “healthy” state of this specific motor type. |

| Alternate bars appear dark and slightly recessed while others look bright, and the brush track is patchy along the circumference. | Segment-to-segment current sharing is uneven, often due to unequal contact pressure, local contamination, or magnetization asymmetries in the field system. | The motor has zones where it sounds rough, vibration varies with load, and brush heating is concentrated in certain regions. | You check spring forces and brush holders, verify field symmetry, and sometimes turn and undercut the commutator to reset the surface condition. |

| Localized burn marks or blue-black spots appear on one region of the commutator, often lining up with one coil group. | There is chronic poor commutation in that coil set, from insulation degradation, high inductance, or mis-set interpoles that fail to assist those coils correctly. | Under load, the motor throws visible sparks at specific angular positions, brushes chip, and you may see radio-frequency interference. | You trace the associated armature circuits, test coil resistance, review interpole polarity and magnitude, and consider partial or full rewinding. |

| The whole commutator looks rough with ridges or grooving, and the brush wear is heavy with lots of carbon dust in the housing. | Brush grade is mismatched to the surface speed or current, contact conditions are abrasive, or the environment is contaminated with particulates. | The unit runs hot, efficiency drops, starting becomes less predictable, and maintenance intervals become very short. | You review the brush material choice, reconsider cooling and filtration, and often re-machine the commutator before introducing a better brush and sealing strategy. |

| The surface looks good but there is persistent light sparking and a high, stable brush voltage drop. | The brushes are forming an overly resistive contact film or the springs are set too lightly, so the effective contact area is low. | There is mild EMI, modest extra heating, and sometimes control electronics misbehave in sensitive systems. | You adjust spring pressure within limits, possibly move to a slightly different brush composition, and recheck the supply quality. |

A surprising amount of “commutator problems” are really brush-holder alignment, spring, contamination or supply issues. The copper bars are just the place where those problems leave marks.

Design choices hidden inside “just a commutator”

When you choose a DC motor or design one, the commutator forces several quiet decisions.

Segment count versus voltage. Higher terminal voltage usually drives you toward more segments, because each bar-to-bar transition carries less voltage and is easier to switch without excessive sparking. But more segments mean tighter tolerances, more risk of eccentricity, and more time in machining and inspection.

Brush grade versus duty cycle. Intermittent tools can live with aggressive copper-graphite grades that give low drop and accept higher wear. Continuous-duty machines want brushes that can maintain a stable film for thousands of hours without dramatic dimensional change. The same motor, used differently, may deserve a different commutator–brush pairing.

Environment versus safety. Sliding contacts generate carbon and copper dust. In explosive atmospheres or sealed clean systems, this is a problem. There is also the persistent sparking risk. That is why large high-power drives in industry moved away from commutated DC machines toward AC induction or synchronous machines, and more recently to brushless DC with electronic commutation.

Manufacturability versus performance. Molded one-piece commutators dominate in small appliances; they are not designed to be repaired. Refillable dovetail constructions show up in larger machinery where resurfacing and segment replacement are economical.

Each of these levers shows up eventually in the cost of downtime, not just in the bill of materials.

Mechanical commutation vs electronic commutation

Modern drives keep pushing electronics harder, so it is natural to compare the commutator to solid-state switching in a brushless DC motor. Both are answering the same question: “How do we ensure the armature current stays aligned with the useful torque-producing field?”

The mechanical commutator uses rings, segments and brushes. Position sensing is implicit: conductors are connected to different segments purely by rotation. Timing is locked to the geometry, which is beautifully simple until you want arbitrary current waveforms, field weakening profiles, or sensorless control tricks. Efficiency losses appear as brush drop, friction, and wear.

Electronic commutation uses sensors (or estimators) with semiconductor switches. You replace brush and commutator copper losses with switching and conduction losses in the power stage. Thermal management moves from rotating copper to static silicon and busbars. The upside is that current shape, torque control, and protection can all be done in software and control hardware; the downside is that you have more components and a different failure pattern.

For small, very cost-sensitive devices where control needs are modest, the old mechanical commutator is still used because it avoids controllers and position sensors. For almost everything requiring high life, low maintenance, or sophisticated control, electronic commutation has taken over.

Where commutator research is still alive

It might feel like brushed DC technology is frozen, but there is ongoing work. Recent studies explore improved brush materials, including carbon structures doped with metals or even nanotube-based composites, to reduce wear and stabilize contact resistance.

There is also interest in monitoring commutator condition via vibration and electrical signatures. With low-cost sensing and embedded processing, it becomes possible to detect evolving defects from subtle changes in brush noise or bar-to-bar voltage patterns before there is visible damage.

These directions keep the technology relevant where replacing a whole drive system is not practical, even as new projects default to brushless architectures.

A practical way to think about the commutator

If you already know the textbook diagrams, it can help to mentally reframe the commutator as three overlapping things.

It is a time-variant connection matrix between armature coils and the external circuit. At each rotor angle, it decides which coils are in circuit and with what polarity.

It is an analog switch that must force current in inductive coils to reverse on a tight schedule without wasting too much energy as heat and arcs.

It is a mechanical surface that has to survive sliding contact at high speed with a controlled amount of wear and debris, under sometimes harsh thermal and environmental conditions.

Once you see it that way, faults stop looking mysterious. Most issues fall into one of three categories: the connection sequence is wrong (geometry, magnetics, wiring), the switching is stressed (inductance, supply, interpoles), or the surface mechanics are unhappy (brushes, springs, contamination). And the DC motor stops being “just a motor” and becomes a system where the commutator is the quiet, rotating contract between all those constraints.