What Is A Commutator Made Of?

A commutator is mostly copper and carbon, stitched together with mica, steel or plastic, and resin. Copper segments carry current, mica keeps them apart, the hub holds everything on the shaft, and carbon-based brushes slide on the surface to close the circuit. That’s the whole story in one line; the rest is how strongly, how long, and how cleanly it does that job.

Table of Contents

The quick material snapshot

If you strip a typical DC motor or generator down to the commutator, you usually find three main bodies of material.

The working face is a cylinder made of narrow copper segments arranged around the shaft. Each segment is individually insulated from its neighbor, historically by mica but now often by engineered plastics in smaller machines.

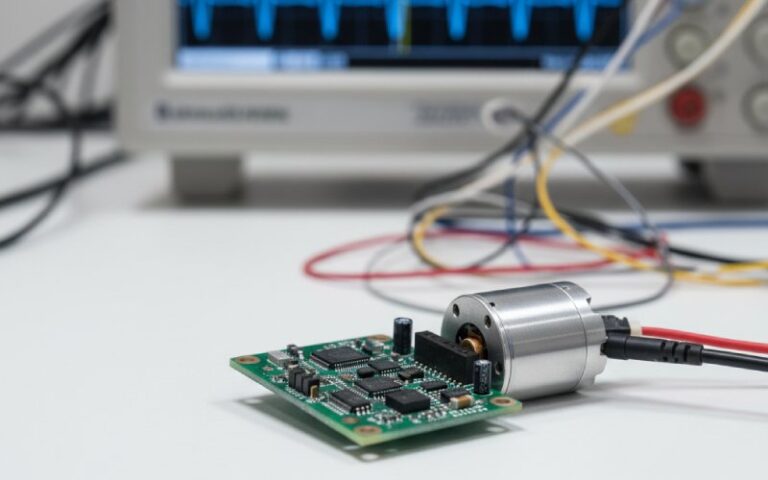

Those segments are locked into some kind of hub or shell. Older and larger machines favor a steel hub; a lot of modern small motors use a molded plastic body with copper bars embedded inside, plus metal bushings to transfer torque to the shaft.

Pressed against the copper surface are the brushes. They are not part of the commutator ring itself, but functionally they live in the same small world, so you cannot talk about “what it’s made of” and ignore them. Most modern brushes are grades of carbon and graphite, sometimes loaded with copper or other metal powders.

That is the basic stack: copper, insulation, hub, brushes. Now the interesting detail is which exact flavors of each you pick and why.

Copper segments: not just “copper”

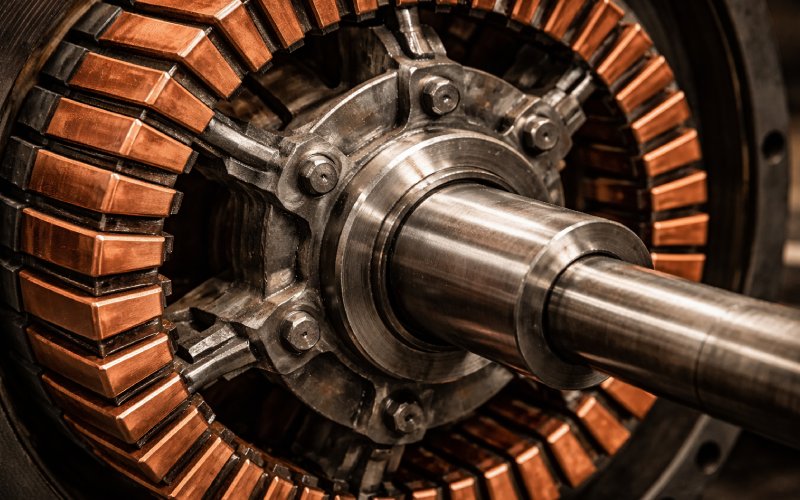

Segment material is usually high-conductivity, hard-drawn copper. Pure copper keeps resistance low so the commutator does not waste power or heat itself unnecessarily; the hardness is pushed up by cold work or small alloy additions so the bars do not smear under brush pressure at speed.

Large industrial machines, with high current density and high peripheral speed, often use carefully specified copper alloys with slightly higher hardness and good wear behavior. The design trade is simple. Softer copper gives a forgiving surface for carbon brushes but wears fast. Harder copper lasts longer and holds geometry better but can increase brush wear and contact noise if the system is not tuned.

The copper bars are wedge-shaped in cross-section, thicker at the outer surface and thinner near the shaft. This geometry lets them lock into the insulating body and resist the centrifugal forces that try to peel them off at speed. A dovetail or similar shape on the underside of each segment is common; it mechanically keys the bar into the hub or molded shell without needing excessive adhesive.

On high-power equipment, individual segments are often replaceable. That pushes material choice toward stable alloys and machining processes that keep the surface clean and straight after multiple refacing cycles.

Insulation between segments: mica and engineered plastics

The copper bars must be electrically separate but mechanically unified. That tension is carried almost entirely by the insulation.

Traditional commutators use thin mica segments between copper bars and often as a cylindrical sleeve between the copper stack and the steel hub. Mica has very high dielectric strength, keeps its properties at elevated temperature, and tolerates the pressure of the clamping and banding operations needed during manufacture.

Modern small motors frequently shift to polymer systems. Semi-plastic commutators embed copper bars into a molded plastic shell, with mica or other insulators still present between bars, and metal bushings molded in for mechanical support. The plastics are usually thermoset or high-temperature thermoplastics that can handle hot spots at the brush track without softening.

Whatever the exact recipe, the machining step always ends with undercut mica or plastic between the bars at the working surface. If the insulating material is flush with the copper, brushes will ride on both and lose stable contact; undercutting lets the brush material bridge the gap and keeps the current path concentrated into the copper.

Hub, shell, and mechanical backbone

The commutator needs a backbone that pins the copper and insulation to the rotor shaft.

Big DC machines often use a forged or machined steel hub. The copper and mica stack is assembled around this hub and clamped, banded, or shrink-fitted. Steel gives the required stiffness and allows fairly high peripheral speeds without excessive growth under centrifugal load.

Smaller and medium-power motors increasingly use molded semi-plastic designs. A plastic shell captures copper bars and mica sheets, and a metal bushing is inserted in the center for the shaft fit. This cuts cost and assembly time, at the price of lower maximum speed and a bit more sensitivity to heat cycling.

Resins and adhesives tie everything together. Phenolic or epoxy systems are common, chosen less for “magic properties” and more for the familiar trio: adequate temperature resistance, predictable shrinkage on cure, and good adhesion to both copper and insulation.

Brushes: the “other half” of the material system

If you only specify commutator materials and ignore brush composition, you are only doing half the job. The material pair is what matters.

Most DC machines today use carbon brushes. The base material is mixtures of natural and artificial graphite, with binders that carbonize during high-temperature treatment. These mixes produce a material that conducts enough for motor currents, but is soft and lubricious enough to slide on copper without tearing it up.

Different brush families exist:

Electrographite grades are graphitic materials treated at very high temperature. They tolerate higher temperature, shed less dust, and run well on hard copper at higher speeds.

Metal-graphite brushes mix graphite with copper or sometimes silver powder. These grades have lower electrical resistance and suit high-current, low-voltage duty; they leave a slightly more metallic film on the copper which alters friction and contact drop.

On very small or intermittent-duty motors, you still find pure metallic brushes, often copper or copper mesh, because cost and compact size matter more than long-term wear.

If the commutator uses very soft copper or a plastic-heavy structure, brush grades tend to shift to softer, more graphitic types. Hard commutators with robust hubs can run harder, more metal-rich brushes without structural risk. The matching is deliberate, not an afterthought.

A compact material cheat sheet

Here is a simplified view of what the main pieces are made from and why.

| Component part | Typical materials | Key reasons these are used |

| Copper segments | High-conductivity hard-drawn copper; copper alloys with small additions for hardness | Low resistance for current transfer, enough hardness to keep surface form under brush load, good machinability and balance at speed |

| Inter-segment insulation | Mica sheets; engineered plastics in small machines | High dielectric strength, thermal stability near the brush track, ability to withstand clamping pressure and machining without cracking |

| Hub / shell | Steel hub on larger machines; molded thermoset or high-temp thermoplastic shells with metal bushings on small motors | Structural backbone, torque transfer to shaft, dimensional stability under centrifugal forces and heat cycles |

| Bonding system | Phenolic or epoxy resins, sometimes glass or steel bands | Locking of copper and insulation stack, control of shrink fit, mechanical damping at high speed |

| Brushes | Carbon / graphite, electrographite, metal-graphite, metallic copper in small toys | Sliding contact with acceptable wear, controlled contact voltage drop, arc behavior matched to copper and duty cycle |

How commutator materials shift with size and duty

Once you know the basic material menu, the patterns by application come into view.

Small appliance and tool motors, which often run at very high speed and are cheap to replace, lean toward molded commutators with embedded copper bars and plastic shells. The brushes are often metal-graphite or graphitic grades aimed at short, intense operating periods. Motor failure usually means motor replacement, not commutator repair, so long repairability is not a design goal.

Industrial DC motors and DC generators, with ratings from a few kilowatts upward, still rely on more traditional copper-and-mica stacks keyed to steel hubs. Segments are refillable and mica can be replaced and undercut again. The brushes are carefully graded carbon materials, often with detailed supplier data on current density, film behavior, and voltage drop. Correct material pairing and maintenance can keep such commutators running for many years with periodic resurfacing.

Special cases exist. High-precision servo motors and some traction applications may specify quite particular copper alloys and brush grades to control radio-frequency noise, or to handle unusually high current ripple from power electronics.

Material choice and failure signatures

If a commutator smears, ridges, burns, or throws segments, the failure pattern usually points back to material choice or limits.

Smearing and excessive grooving on the copper bars often indicate a surface that is too soft relative to the brush grade and load. Harder copper or softer brushes, or both, are the levers to pull.

Mica high-spots or lifted wedges signal issues with the insulation system. Either the mica is not undercut correctly, or the resin and mechanical clamping do not hold the stack under thermal cycling. The solution is less a mystery material and more correct machining and assembly around the mica’s known properties.

Brush dust packing between segments or across the surface points at an unhappy brush / commutator pairing: maybe too much metal in the brush, or surface temperature in a region where the binder behaves poorly. Here the material change is usually on the brush side rather than the copper.

Cracked plastic shells in semi-plastic commutators show up in overload or high-temperature service beyond the intended envelope. Once the shell fractures, segment alignment goes, and no brush grade will save the geometry. That is where the simpler steel-hub, copper-and-mica designs still earn their place.

Stepping back

So when someone asks what a commutator is made of, you can answer in one sentence and still be accurate: copper segments, separated by mica or engineered insulation, mounted on a steel or plastic hub, and working against carbon-based brushes. The interesting work for designers and maintainers lies underneath that short answer, in choosing specific alloys, graphite mixes, plastics, and resins that survive the exact duty the machine will see.