What Does a Commutator Do in a DC Generator?

In a DC generator, the commutator takes whatever messy alternating voltage the armature coils produce and quietly flips connections so the output at the terminals always pushes current in one direction. At the same time it limits how big the machine can be, how fast it can spin, how clean the waveform looks, and how much maintenance you’ll be doing. That’s the whole story in one line, even if it sounds too compact.

Table of Contents

Quick answer, without the textbook fluff

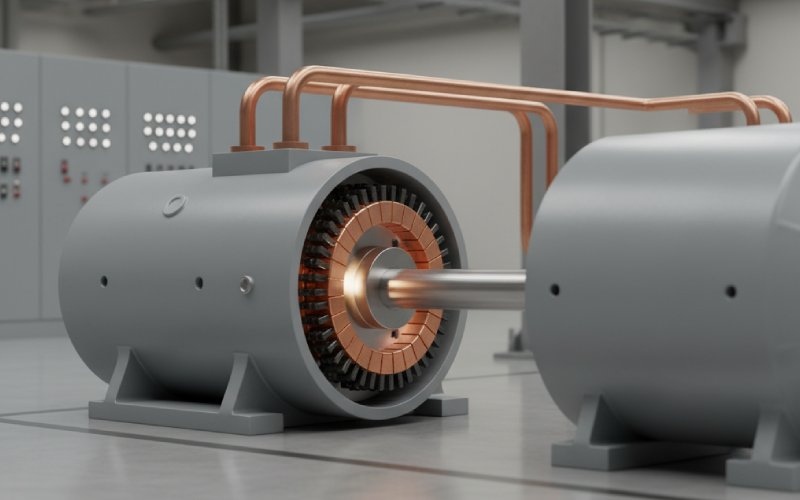

Official documentation usually stops at: “the commutator is a mechanical rectifier that converts internally generated AC into DC at the output.” That’s correct. The copper segments are wired to the armature coils, the brushes sit on top, and as the rotor turns, the segments swap which side of the external circuit each coil is tied to. So the induced voltage in each coil alternates, but the direction of current in the external circuit does not.

That’s the functional core: periodic reversal of coil connections so the external current remains unidirectional, giving you pulsating DC instead of pure AC at the generator terminals.

But that description is only the starting line. The commutator is also the bottleneck, the troublemaker, and the thing that quietly sets half the design rules for a DC generator.

What is really happening during commutation

Think about one active coil sitting under a pole. As it rotates, its induced EMF flips sign when it crosses the neutral zone. Good. Now add a commutator segment for each coil and press a brush against them. For a short angular interval, the brush covers two adjacent segments. During that instant, that particular coil is short-circuited through the brush, and its current must reverse while it is still cutting flux. That brief period is the actual commutation process.

If commutation were ideal, the current in that shorted coil would ramp smoothly from +I to −I during that short time. In reality, the coil has inductance, the armature reaction distorts the field, and the current does not want to change right when you tell it to. That is where sparking comes from. We usually fix it with interpoles and compensating windings, but the root of it is sitting in the commutator geometry and the timing between rotation and brush position.

So the commutator doesn’t only “convert AC to DC.” It imposes a schedule on when each coil is allowed to reverse current, and the rest of the machine is designed around making that schedule survivable.

Why a DC generator without a commutator just becomes an AC machine

Strip the commutator away and replace it with two smooth slip rings. Now each end of the main armature winding goes to one ring, the brushes ride on them, and the external circuit simply sees the same AC that’s induced inside. That’s an alternator. The only big difference is that the commutator chops the winding into many segments and re-routes coil connections every half-turn so the external output is always of one polarity.

From a system level, the commutator is the reason you can directly charge a DC bus or battery from a mechanical shaft without any electronic rectifier. Take it away and you need diodes or power electronics. Add it back and suddenly you’re back to brushes, dust, and regular maintenance.

What the commutator actually does, beyond the one-line definition

The usual one-sentence answer hides several separate jobs that all ride on those copper segments. It’s easier to see them side by side.

| Aspect | Idealized role of the commutator | What really happens in a DC generator | Why it matters in practice |

| Current direction | Keeps external current unidirectional even though each coil sees alternating EMF. | Segment–brush geometry schedules when each coil is flipped into the opposite polarity path. | Determines whether the machine can feed DC loads directly and how “smooth” that DC appears. |

| Waveform shaping | Produces neat stepped DC that averages to a fixed value. | With many segments, the individual pulses overlap and blur into a nearly flat DC with ripple; with few segments, ripple is obvious. | Segment count becomes a design knob for voltage quality versus cost and mechanical complexity. |

| Commutation timing | Reverses current exactly at the magnetic neutral plane. | Armature reaction shifts the neutral plane; brushes are often physically displaced and interpoles are used to restore effective timing. | Incorrect timing gives heating, brush wear, and arcing long before catastrophic failure shows up. |

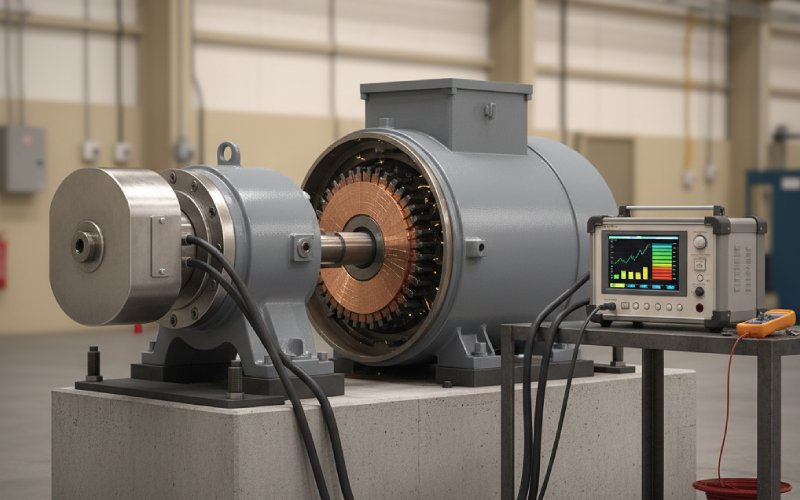

| Mechanical interface | Simple way to couple rotating coils to a fixed external circuit. | Sliding contact with real pressure, dust, and vibration; brush material, spring force, and surface finish all become delicate design choices. | Limits maximum speed, voltage per segment, and total power rating of the machine. |

| Protection against coil open-circuits | Just “connects things.” | A single bad segment or open coil shows up as a periodic notch, vibration, or spark when that segment passes under the brush. | Maintenance teams often diagnose armature faults by watching how symptoms sync with commutator position. |

Once you look at the machine through that table, the commutator stops being a small copper detail and turns into the central constraint.

Design choices around the commutator that rarely get discussed

In theory, you can keep adding segments and coils and get smoother and smoother DC. The limiter is not the mathematics; it is the copper, insulation, and air.

First, there is a maximum allowable voltage per segment. Too much and you get flashover between adjacent bars, especially when the surface is dirty or the air is humid. Designers divide the desired terminal voltage by a safe volts-per-segment number and end up with a minimum number of bars. This is why high-voltage DC generators quickly become awkward; the commutator grows wide, brush rigs multiply, and cost follows.

Second, brush width versus segment pitch sets the commutation window. The brush typically spans more than one segment so that as one coil is coming off, another is coming on, giving overlap. Too narrow and you get dead zones and poor contact; too wide and you short too many segments at once and overload the short-circuited coils.

Third, surface speed makes or breaks the entire idea. At high shaft speed, the relative speed between brush and copper plate increases the rate of wear and intensifies any arcing. That is one main reason the biggest modern machines standardize on AC designs or on brushless DC with semiconductor commutation. The mechanical switch simply does not scale nicely.

All of those decisions fall under “what the commutator does” because its geometry enforces them.

How the commutator shapes the output DC

Imagine a very simple, two-segment commutator. The output voltage is basically a rectified sine wave, positive only, with deep gaps. Add more coils and more segments distributed around the circumference and something different happens: while one coil’s output is falling, another’s is rising, and the commutator stitches those instantaneous voltages together into a stepped pattern with smaller gaps.

This is why small hobby generators have visible ripple, while carefully designed industrial DC generators approach a pretty steady line on a meter, even without filters. The commutator, by coordinating which coils are connected at each moment, is acting almost like a crude analog multiplexer.

So when we say the commutator “converts AC to DC,” we are hiding the fact that it also performs a kind of time-division averaging of many small alternating sources distributed around the rotor.

Commutator, brushes, and the neutral plane

You already know the rule: brushes should sit on the magnetic neutral axis so that during commutation the shorted coil ideally cuts no net flux, minimizing induced EMF and simplifying current reversal. On a real loaded generator, armature reaction pushes that neutral axis over. Leaving the brushes in the theoretical position produces sparking.

Most modern machines fix this with interpoles: small auxiliary poles wired in series with the armature that produce a corrective field just in the commutation region. That extra field cancels the armature reaction locally, dragging the effective neutral plane back where the brushes actually sit.

It looks like a magnetic detail on a drawing, but it’s really another part of “what the commutator does.” It forces you to pay attention to where, in space, you are allowed to reverse current without excessive stress on the copper and carbon.

Commutator vs slip rings in one view

From the outside, both components are just shiny rings with brushes. Inside the machine, their roles are quite different.

A slip ring is continuous, unsegmented metal. It simply carries AC (or DC) from a rotating member to a stationary circuit without changing its waveform. A commutator is intentionally broken into insulated segments and wired to different parts of the armature winding so that rotation automatically re-routes those connections.

So if you ask, “why not use slip rings in a DC generator and then sort the rest out electronically,” you are essentially describing a modern alternator plus rectifier. Industry has already answered that question: for larger ratings and higher speeds, replacing the commutator with smooth rings and letting solid-state devices do the switching is usually simpler.

The legacy DC generator keeps the switching mechanical. That is its defining trait.

Failure modes: what they say about the commutator’s job

Look at common field problems and you can kind of read the commutator’s responsibilities backward.

Heavy sparking and burned bars often mean commutation is taking too long or happening in the wrong magnetic zone. Maybe the brushes have worn into an odd shape, maybe the interpoles are mis-set, maybe there is a shorted turn increasing inductance in a local coil.

Grooved or ridged copper usually traces back to brush material and pressure. Too hard and the copper wears. Too soft and the brush itself erodes quickly, filling the machine with carbon dust. In both cases, the sliding interface that makes commutation possible is being eaten.

Uneven coloring or patina on the segments sometimes indicates non-uniform current sharing among parallel paths. That points back to how the armature coils are connected to the commutator bars and how the magnetic circuit is distributing flux.

In other words, every maintenance symptom is really a small report card on how comfortably the commutator is performing its switching and current-collecting role.

Where commutators still make sense

Despite the rise of brushless machines and semiconductor rectifiers, commutated DC generators still show up in niches: low-voltage portable units, legacy industrial systems, some training labs, specialized applications where a simple mechanical DC source is adequate and the drawbacks are accepted.

Their competitive edge is not sophistication. It is directness. Shaft in, mechanical rectification at the commutator, DC out. No electronics on the power path. Just copper, carbon, and steel timed so that every coil hands off its current at the right angle.