Starter Motor Commutator Bad Spot: The Complete, Human-Friendly Guide

If you’ve ever turned the key and gotten nothing… then tried again and it suddenly sprang to life, you’ve already met today’s topic: the starter motor commutator bad spot.

It’s one of those faults that feels almost personal — random, moody, and impossible to show your mechanic because it behaves perfectly the moment you’re at the shop. In reality, there’s a very specific electrical/mechanical reason for that “sometimes it starts, sometimes it doesn’t” behavior.

- This guide will walk you through:

- What the commutator and brushes actually do (in plain language)

- What a “bad spot” or “dead spot” really is inside the starter

- The specific symptoms that point toward a bad commutator spot vs. a bad battery or solenoid

- Simple at-home checks you can do safely

- When you can get away with a minor clean-up… and when you should just replace the starter

- How to avoid cooking another starter the same way

Table of Contents

1. First, what does a starter motor commutator actually do?

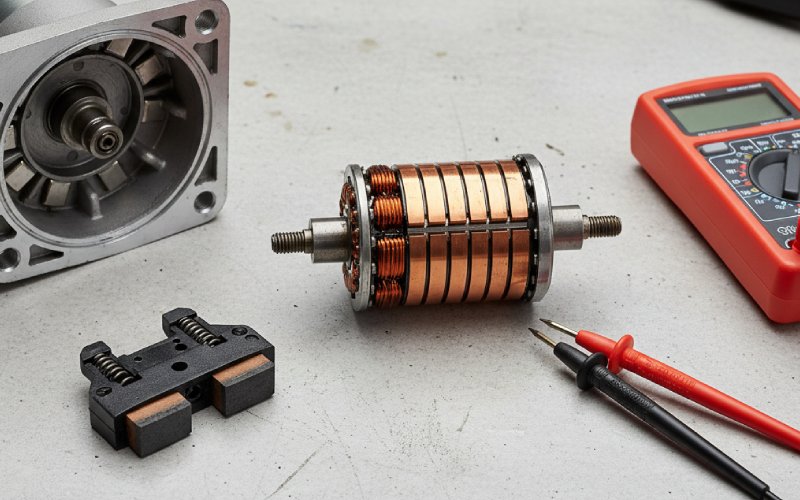

Inside your starter motor is a rotating core called the armature, wound with copper wire. Around the end of that armature is the commutator – a ring made of many copper bars, each insulated from the next. Two or more carbon brushes press against those bars.

As the armature spins, the brushes feed battery power into different windings through those commutator bars, creating a rotating magnetic field that gives the motor its torque. When everything is healthy, this switching happens smoothly and the starter delivers full power every time.

- Key parts involved in a commutator bad spot:

- Battery & cables – supply high current to the starter

- Solenoid – heavy-duty relay that connects the starter to the battery and often moves the pinion gear

- Armature – rotating core inside the starter

- Commutator – segmented copper ring on the armature where brushes contact

- Brushes & brush holders – spring-loaded carbon blocks that ride on the commutator and carry current

- Field windings or permanent magnets – generate the magnetic field that interacts with the armature

2. What is a “bad spot” on a starter commutator?

A bad spot (often called a dead spot) is a localized area on the commutator where the electrical path is damaged or unreliable.

When the starter happens to stop with the brushes sitting on that faulty segment (or pair of segments), the circuit through that part of the armature either opens or shorts in a way that kills torque. The result: you hit the key, everything else may have power, but the starter doesn’t turn at all — until the armature gets bumped off that spot.

This can happen because the commutator bars are worn uneven, burnt, contaminated, slightly lifted from the insulator, or because the internal winding that connects to that bar has gone open or shorted.

- Common causes of a commutator bad spot:

- Worn brushes that no longer press firmly on all commutator bars, especially if the commutator is a bit out-of-round

- Overheated commutator from long cranking or low battery voltage, which can lift bars, carbonize insulation, or pit the copper surface

- Local open or shorted armature winding attached to one commutator segment, causing a dead or weak “zone” as the armature turns

- Heavy dirt, oil, or carbon build-up on a few bars, drastically increasing resistance

- Poor solder joint where the coil connects to the commutator bar, leading to intermittent contact

3. How a bad spot behaves in real life

Unlike a fully dead starter, a commutator bad spot usually shows up as intermittent, maddeningly random no-start events:

Sometimes the motor spins the engine like normal. Other times: nothing. Or just a faint click somewhere under the hood. Try it again… still nothing. Try a few more times… suddenly it cranks strong. That’s the armature finally moving off the faulty segment and landing on healthy ones.

This is why it can be so hard to reproduce in a workshop unless the armature happens to stop in exactly the wrong place.

- Classic symptoms of a commutator bad spot:

- Intermittent no-crank with good battery – dash lights and accessories work fine, but the starter doesn’t turn at all on some key turns

- Starts after multiple key tries – you might have to twist the key 3–10 times before it finally cranks

- Responds to tapping the starter body – a gentle tap sometimes “wakes it up” because the armature moves off the dead spot

- Failure is not strongly tied to temperature – it can be random hot or cold, though heat-soaked windings can make an existing problem worse

- No grinding noise – when the problem is the commutator, you usually don’t hear gear grinding; that’s more about the pinion and flywheel teeth

- Problem slowly gets worse over weeks/months, not better

4. Is it really the commutator… or just the battery or solenoid?

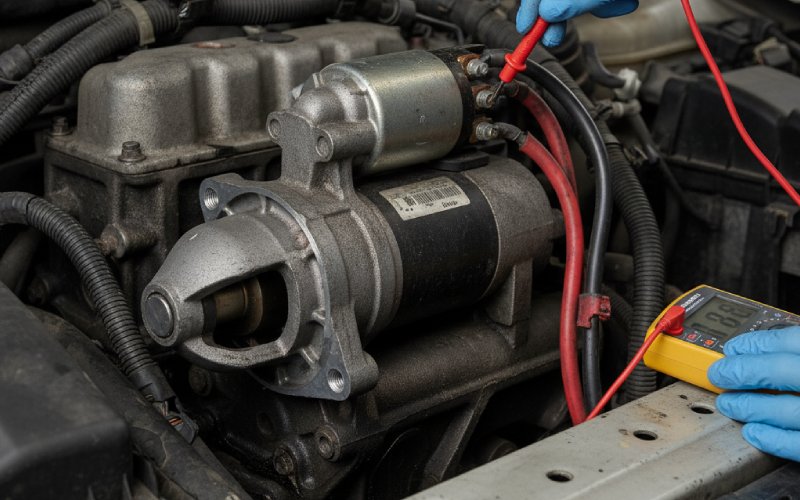

Before blaming the commutator, you want to rule out simpler things. Many “starter problems” turn out to be weak batteries, corroded cables, or faulty solenoids/relays.

Think of it like this: the starter sits at the end of a long chain – battery → cables → ignition switch/relay → solenoid → starter. A break anywhere in that chain can mimic a dead spot.

- Quick driveway checks before you blame the commutator:

- Lights test – do the headlights stay bright while you try to crank? If they dim hard or go out, the battery or connections are suspect.

- Listen for the solenoid click –

- No click at all: may be ignition switch, relay, solenoid coil, or no power to it.

- Loud single click, but no motor: could still be internal starter/commutator, but also solenoid contacts or bad power cable.

- Check battery terminals & grounds – clean off white/green corrosion, make sure clamps are tight.

- Try a jump-start – if a jump pack or another car makes it crank normally every time, low battery or voltage drop is more likely than a commutator issue.

- Scan for codes (on modern cars) – some vehicles log starter circuit or immobilizer issues that can confuse the diagnosis.

5. At-home tests that specifically hint at a commutator bad spot

Once you’re fairly sure the battery and cables are good, you can pay more attention to the starter itself.

What you’re looking for is consistency: does the starter always fail in the same way, or does it seem like it’s playing roulette? A commutator bad spot is, by nature, position-dependent. If the armature just happens to stop in a “good” position, the next start is fine. If it stops on the bad spot, the next start is dead.

Even without tearing the car apart, you can still gather useful clues.

- Tell-tale driveway behaviors:

- Try starting in neutral vs. park (auto) – if it behaves the same, the neutral safety switch is less likely.

- Turn the engine slightly between attempts – on a manual, put it in gear and rock the car an inch; on some engines you can put a wrench on the crank pulley. If it starts immediately after you’ve moved the engine a bit, you may have just rotated the starter off the dead spot.

- Tap test – have a helper hold the key in “start” while you gently tap the side of the starter body with a small rubber mallet or piece of wood (never on plastic or fragile parts). If it suddenly springs to life, that’s classic commutator/brush territory.

- Pattern over time – write down when it fails (cold/hot, first start of day, after short trips). A random scatter of failures with good voltage leans toward internal starter issues.

6. Deeper diagnosis (for the more hands-on)

If you’re comfortable removing the starter (and it’s not buried under an engine bay from hell), you or a rebuilder can run more precise tests. Professional rebuilders do this all the time with growlers, insulation testers, micrometers, and lathes.

On the bench, a bad commutator spot is often obvious: burned or discolored bars, lifted segments, grooves, or an obviously out-of-round commutator. A continuity test across the armature segments can reveal open or shorted coils.

- Typical bench checks for a bad spot (simplified overview):

- Visual inspection

- Look for blue/black burning on a few bars

- Check for raised or loose commutator segments

- Inspect brushes for uneven wear or very short length

- Commutator roundness

- Rotate it next to a fixed pointer or dial indicator

- Notice if some bars “dip” or “stick out” more than others

- Resistance checks

- Measure resistance between adjacent commutator bars; a big jump or near-zero reading on one pair can indicate open or shorted windings

- Insulation tests

- Higher-end shops use a “drop test” or growler to detect shorts between coils or to the core

- Lathe cleanup (if still serviceable)

- Lightly turn the commutator, then undercut the mica insulation between bars, and fit new brushes if needed

- Visual inspection

⚠️ Note: Serious armature testing and commutator machining is best left to someone with the proper tools. A poor DIY cut on the commutator can make problems worse or permanently ruin an otherwise rebuildable armature.

7. Repair vs. replace: what’s realistic?

Modern automotive starters are often treated as complete units – when something internal fails, most shops simply replace the entire starter with a new or remanufactured assembly instead of rebuilding it piece-by-piece.

That said, for some vehicles (especially older cars, tractors, motorcycles, and marine engines), rebuilding is still common. In those cases, a bad commutator spot might be correctable with cleanup, machining, and new brushes – depending on how severe the damage is.

Here’s a comparison to help you think it through:

| Option | What it involves | Pros | Cons | Best for |

| Replace starter with new OE or quality aftermarket | Swap entire unit | Highest reliability, fresh bushings/solenoid/armature, warranty | More expensive than a simple clean-up | Daily drivers, hard-to-access starters, modern cars |

| Replace with remanufactured starter | Professionally rebuilt unit | Cheaper than new, often tested and warranted | Quality varies by rebuilder; may reuse some old parts | Most budget-conscious repairs where you still want reliability |

| Professional rebuild of your starter | Shop re-machines commutator, replaces brushes & wear parts, repairs windings if feasible | Keeps original housing/mounting, great for rare/obsolete models | Labor intensive, can approach cost of reman; not every shop offers it | Classics, marine, industrial gear, rare vehicles |

| DIY clean & brush replacement | Disassemble, clean commutator & internals, fit new brushes | Cheapest, satisfying if you’re handy, good learning experience | Risk of misassembly; may not fix underlying bad winding/segment; no warranty | Hobbyists, backup vehicles, experimentation |

- Factors that push you toward full replacement instead of repair:

- Starter is extremely difficult to access (you only want to do this once)

- Commutator shows severe burning, cracks, or loose/lifted bars

- Multiple symptoms: noisy bearings, grinding engagement, plus intermittent no-start

- Vehicle is your only transport and downtime is costly

- Rebuild parts or local specialists are hard to find

8. “Tapping the starter” and other roadside tricks (use with care)

Let’s talk about that advice: “Just whack the starter with a hammer.”

This trick exists for a reason. A gentle tap can indeed vibrate the armature just enough to move the brushes off a dead commutator segment, and the starter will suddenly come back to life. Many techs use this as a quick test for worn brushes or a bad commutator segment.

But it’s a temporary workaround, not a fix. And it can cause damage if done carelessly.

- If you absolutely must try the “tap trick”:

- Use a small rubber mallet or piece of wood, not a big steel hammer.

- Tap the sturdy metal body of the starter, not the solenoid terminals, plastic end caps, or wiring.

- Have a helper hold the key in “start” while you tap once or twice; do not go to town beating on it.

- Treat success as a diagnostic clue, not permission to ignore the problem.

- Remember: if it responds to tapping, internal starter service or replacement is due soon.

9. How to avoid another bad spot in the future

Starters don’t live forever, but you can greatly extend their life – and reduce the odds of another commutator bad spot – by treating them kindly. A lot of commutator damage comes from overheating, low voltage, or repeated abuse.

- Starter-friendly habits:

- Limit crank time – don’t hold the key in “start” for more than 10–15 seconds at a time; let it cool for 30–60 seconds between attempts.

- Fix hard-starting engines quickly – if it’s cranking a long time due to fuel/ignition issues, the starter is just collateral damage.

- Keep the battery healthy – low voltage makes the starter draw more current, which overheats windings and commutator bars.

- Inspect cables and grounds yearly – clean and tighten major power and ground connections; bad grounds cook starters.

- Listen to early warning signs – intermittent clicks, slow cranking, or needing multiple key turns are your cue to test and fix, not something to ignore.

10. When should you stop driving and fix it?

If your starter occasionally hesitates but always eventually cranks, it’s tempting to shrug and keep rolling. The problem is that commutator bad spots almost never “heal.” They usually get worse until you’re completely stranded.

For most people, the smart time to act is as soon as you can reproduce the failure at least a couple of times and you’ve ruled out the battery and cables. If tapping the starter or rocking the car makes it suddenly work, that’s your starter pleading for retirement.

- Good rules of thumb:

- Plan repair soon if:

- You’ve had more than 2–3 no-crank events in a week

- A gentle tap or rocking the vehicle makes it start

- You see obvious corrosion or damage when you peek at the starter

- Tow it or avoid driving if:

- It now fails more often than it works

- You’re about to take a long trip or travel somewhere remote

- The starter is making new noises (screeching, grinding, high-pitched whine) in addition to the intermittent no-start

- Plan repair soon if:

11. Wrapping up: making sense of the “random” no-start

A starter motor commutator bad spot feels random from the driver’s seat, but inside the motor it’s very logical: a damaged or poorly contacting segment of copper that occasionally breaks the current path right when you need it.

By understanding how the commutator and brushes work, paying attention to the exact symptoms, and doing a few simple tests, you can tell the difference between:

- a weak battery,

- a bad solenoid or cable,

- and a starter whose commutator has simply reached the end of its life.

If you’re already at the “tap it to make it start” stage, that starter is living on borrowed time. The kindest thing you can do for yourself (and your future self on a rainy night) is to plan a proper fix — whether that’s a quality replacement starter or a professional rebuild.