Split Ring Commutator vs Slip Ring: The Clear, Real-World Guide

If you work with rotating machinery long enough, two pieces of jargon will keep poking you in the ribs: slip rings and split-ring commutators. On paper they sound almost the same. In the real world, confusing them can mean a motor that just buzzes instead of turning, or a design that’s noisy, high-maintenance, or simply doesn’t work.

At a human level, here’s the difference:

- A slip ring is like a rotating extension cord that keeps the same polarity all the way through. It’s about continuous connection between stationary and rotating parts.

- A split-ring commutator is like a mechanical polarity flip-switch timed with rotation. It’s about reversing current at exactly the right moments to keep a DC motor or DC generator behaving properly.

Table of Contents

1. First, the 20-second “Split Ring vs Slip Ring” answer

If someone stops you in the lab and asks:

“Quick, what’s the difference between a slip ring and a split ring commutator?”

the simplest truthful answer is:

- Slip ring → Continuous ring that passes power or signals between a stationary and rotating structure without changing polarity. Used in things like AC generators, wind turbines, radar antennas, cable reels, and rotating camera systems.

- Split-ring commutator → Segmented ring (usually two halves) that reverses DC current in a motor or generator winding every half turn, so torque or output stays in one direction. Found in DC motors and DC generators only.

- If you only remember one rule of thumb, make it this:

- Need continuous rotation with unchanged polarity? → Slip ring.

- Need to flip DC polarity in sync with rotation? → Split-ring commutator.

- Need continuous rotation with unchanged polarity? → Slip ring.

2. Visualising what’s going on (without scary math)

Imagine you’re trying to power a rotating carousel with lights on it. If you just ran wires from the floor to the spinning part, they’d twist up, snap, and probably take someone’s hat with them.

A slip ring solves that by giving the carousel a circular “track” of metal. Stationary brushes press on that track and feed power into the rotating structure. Current goes up through the ring, out to the lights, and never swaps direction just because it’s turning.

A split-ring commutator lives a different life. Picture a simple DC motor: a coil inside a magnetic field. For that motor to keep turning the same way, you must reverse the current through the coil every half revolution. The commutator does that by swapping which armature coil terminal connects to which brush as it rotates – like a perfectly choreographed mechanical DJ, cross-fading between “+” and “–” at just the right time.

- In other words:

- Slip rings connect.

- Split-ring commutators switch.

- Slip rings connect.

3. Inside a slip ring: what’s really happening?

At its heart, a slip ring is surprisingly simple:

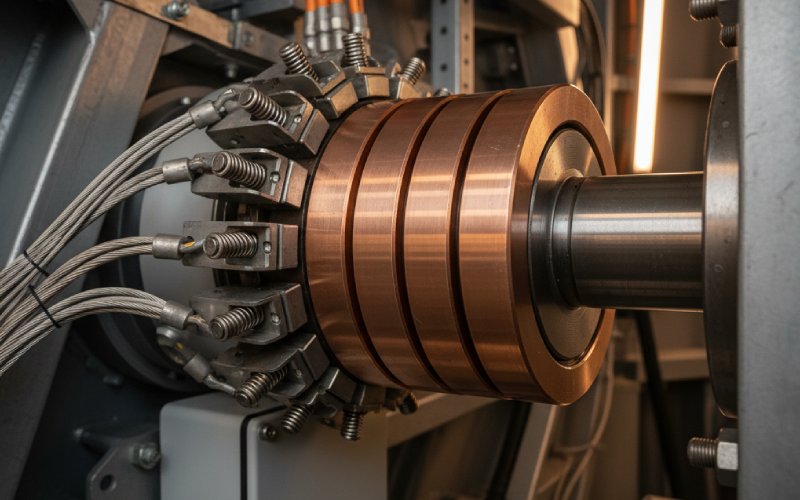

You have one or more conductive rings mounted on a rotating shaft, and stationary brushes that press against those rings. As the shaft spins, the brushes maintain contact, letting current or signals flow across the rotating interface.

Engineers love slip rings because they:

- Allow unlimited rotation (no cable twisting)

- Can carry power, signals, or high-speed data

- Can be customized: from tiny capsule slip rings in pan-tilt cameras to huge multi-ring assemblies in wind turbines and cranes

- Typical slip ring building blocks:

- Rings – copper, brass, or precious-metal plated tracks on a rotor

- Brushes – graphite, metal-graphite, or precious-metal wires on the stator

- Housing – protects from dust, moisture, vibration

- Bearings – ensure smooth rotation and consistent brush pressure

- Optional extras – integrated rotary unions for fluids, fiber-optic joints, high-frequency RF paths, etc.

- Rings – copper, brass, or precious-metal plated tracks on a rotor

4. Inside a split-ring commutator: the mechanical rectifier

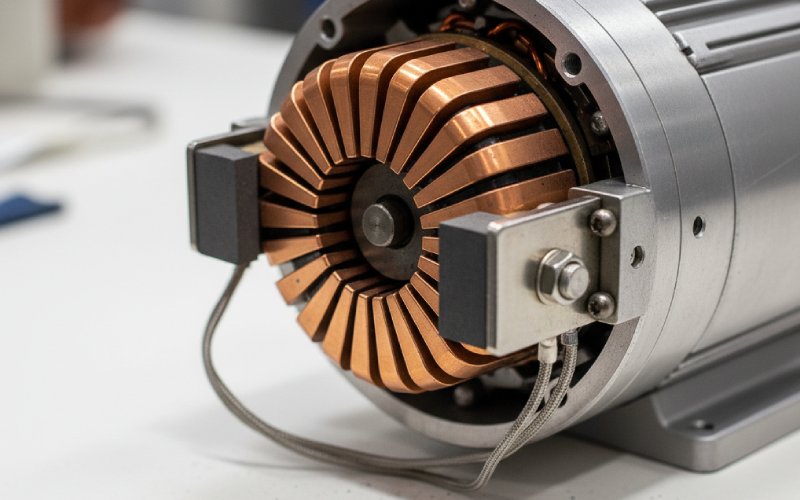

A split-ring commutator looks like someone took a slip ring and sliced it into insulated segments. In the simplest DC motor, you usually see two copper half-rings, each connected to one end of the armature coil.

Here’s what it’s doing while the motor runs:

- As the coil rotates, one side of the commutator is connected to the positive brush, the other to the negative brush.

- When the coil reaches the “flip” position (vertical in many textbook diagrams), the brushes slide onto the opposite segments.

- That swap reverses the current in the coil exactly when the magnetic torque would otherwise change direction.

- The result: torque on the motor shaft keeps pushing in one consistent rotational direction, so the motor doesn’t stall or bounce back.

Engineers sometimes call the commutator a mechanical rectifier: it takes AC-like current in the rotating windings and presents a DC-like output at the brushes in a generator, or vice versa in a motor.

- Key features of a split-ring commutator:

- Made of multiple insulated segments (two in simple school motors, many more in real DC machines)

- Segments are wired to different armature coils

- Brushes are fixed in space; the segments move under them

- Its job is timing, not just connectivity – switching at the exact mechanical angle each turn

- Made of multiple insulated segments (two in simple school motors, many more in real DC machines)

5. Split Ring Commutator vs Slip Ring – comparison table

Here’s a practical side-by-side you can drop straight into design docs or training material:

| Aspect | Slip Ring | Split-Ring Commutator | What it means for you |

| Basic role | Maintain continuous electrical connection between stationary and rotating parts | Periodically reverse current in rotor windings (DC machines) | Choose slip ring when you just need power/data transfer; choose commutator when DC torque or DC output needs polarity flipping |

| Ring construction | Continuous circular rings, no gaps | Segmented rings (usually 2+ insulated segments) | If you see insulation gaps and many segments, you’re almost certainly looking at a commutator |

| Polarity behaviour | Polarity at the rotor side is the same as the supply (ignoring small drops) | Polarity at the rotor side reverses every half turn (or per segment pass) | Wrong choice here = motor that jerks instead of running smoothly |

| Typical current type | AC or DC power, plus analog/digital signals | Mostly DC motors and DC generators | AC alternators use slip rings; classic brushed DC machines use commutators |

| Common applications | AC generators, slip-ring induction motors, wind turbines, cranes, radar, CT scanners, rotating cameras, packaging machines | Brushed DC motors, DC dynamos, small educational motors, some specialty DC drives | Look at your machine type first – that usually tells you which one you need |

| Effect on waveform | Preserves waveform; just adds some noise / contact resistance | Shapes or rectifies waveform (AC in the armature, more DC-like at the brushes) | If you need a smooth DC output from a rotating coil, you need a commutator |

| Maintenance emphasis | Brush wear, contact resistance, noise, environmental sealing | Brush wear plus segment insulation, mica undercut, commutator roundness | Commutators are generally more maintenance-intensive than simple slip rings |

| Design freedom | Many circuits, mixed power/signal, flexible layouts, low or high speed | Strongly constrained by motor geometry and magnetic design | Slip rings are usually more modular; commutators are part of the machine’s heart |

- When explaining to non-electrical colleagues:

- Call a slip ring a “rotating connector”.

- Call a split-ring commutator a “rotating polarity switch”.

- Call a slip ring a “rotating connector”.

6. How a slip ring works – step-by-step

Let’s zoom in on a single circuit passing through a slip ring:

- Stationary side

A cable from your power supply or controller is bolted or soldered to a brush holder. - Brush contact

A brush (graphite block, wire bundle, or precious-metal finger) presses gently against a rotating metal ring. - Rotating ring

As the shaft spins, the ring slides under the brush. The contact patch moves, but the electrical path remains continuous. - Rotating load

On the other side of the ring, a cable runs into the rotating equipment: motor rotor, sensor, heater, encoder, camera, etc.

Because the rings are continuous, the polarity is preserved: what you call “+” on the stator is still “+” on the rotor for that circuit. If your application ever needs long-term rotation without polarity reversal, slip ring is your safe default.

- Practical design knobs for slip rings:

- Number of rings – how many independent circuits you need

- Current per ring – from mA for sensors to kA for large motors

- Voltage rating – clearance/creepage distance between rings

- Signal integrity – shielding, twisted pairs, controlled impedance for data

- Environment – temperature, dust, moisture, vibration, hazardous areas

- Number of rings – how many independent circuits you need

7. How a split-ring commutator works – step-by-step

Take the classic school-lab DC motor as an example:

- A coil of wire sits in a magnetic field between north and south poles.

- Each end of the coil is connected to a different commutator segment.

- Two fixed brushes press on those segments and connect to a DC supply.

- As current flows, one side of the coil experiences a magnetic force upward, the other downward – so the coil starts to rotate.

- After half a turn, if the current direction stayed the same, the torque would reverse and the motor would try to turn back.

- Instead, at that half-turn position the brushes now touch the opposite segments, so the current in the coil flips.

- Torque stays in the same rotational direction, and the motor keeps spinning.

This timing is everything. If the commutator is badly aligned, worn, or contaminated, your torque ripples, the motor may spark heavily, and efficiency nosedives.

- In a real industrial DC motor the commutator:

- Has many segments, each tied to different armature coils

- Reduces torque ripple by distributing switching events

- Is carefully machined round and undercut between segments

- Needs regular inspection for pitting, burning, and uneven wear

- Has many segments, each tied to different armature coils

8. When to use slip ring vs split-ring commutator (decision guide)

Most of the time, the right choice falls out of just a few questions.

Question 1 – Is your machine fundamentally AC or DC on the rotating side?

If the rotating windings or loads are fed with AC (like an alternator or slip-ring induction motor), you almost always use slip rings. The job is to let AC power go in or out without getting twisted, not to flip polarity.

If you’re dealing with DC motors or DC generators, you’re in commutator territory. The physics of DC torque and DC generation demand that periodic reversal.

- Quick decision bullets:

- Rotating sensors, data, camera, heater, LED ring? → Slip ring.

- AC alternator rotor excitation? → Slip ring.

- Brushed DC motor, classic dynamo? → Split-ring commutator.

- You want to convert rotation-induced AC into usable DC mechanically? → Commutator.

- You just want to feed whatever the controller gives you through a rotating joint? → Slip ring.

- Rotating sensors, data, camera, heater, LED ring? → Slip ring.

9. Pros and cons in real projects

From the outside, both components look like “some rings and brushes”. From a lifecycle and maintenance perspective, they behave very differently.

Slip ring – strengths

Slip rings shine when you care about:

- Low design friction – you can route power, control, and data all through one device

- Flexibility – standard modular designs scale from a few circuits to hundreds

- Unlimited rotation – ideal for continuous 360° motion

- Compatibility with modern control systems – Ethernet, fieldbus, encoder signals, video, RF, etc.

Their weaknesses mainly show up as:

- Brush wear and contact noise at high speeds or in dirty environments

- Slight resistance and noise that may need filtering for sensitive analog signals

- The need for sealing and sometimes heaters in harsh outdoor or marine conditions

- Split-ring commutator – strengths vs weaknesses:

- Strengths

- Essential for classic brushed DC machines

- Provides simple mechanical rectification (no power electronics needed)

- Good starting torque characteristics in DC motors

- Essential for classic brushed DC machines

- Weaknesses

- More sparking/arcing, especially under high load or poor maintenance

- More complex geometry → harder and more expensive to manufacture well

- Typically higher maintenance: undercutting, resurfacing, brush optimization

- More sparking/arcing, especially under high load or poor maintenance

- Strengths

10. Common misconceptions (and how to avoid them)

Because the words sound so similar, it’s easy to bump into misleading statements – even in textbooks or marketing blurbs.

One common mistake: people say “commutator ring” when they mean “slip ring”, or they’ll call any ring-and-brush arrangement a “commutator”. In strict electrical engineering terms, that’s not correct:

- Slip ring → continuous ring, doesn’t inherently change current direction

- Commutator (split-ring or multi-segment) → explicitly designed to periodically reverse current in DC machines

Another trap is assuming that split rings are just “two slip rings stuck together”. They are:

- Segmented and insulated from each other

- Oriented relative to the field so switching happens at precise angles

- Mechanically and magnetically integrated into the machine design

If you swap a real commutator for two plain slip rings in a DC motor, the motor will likely:

- Turn a little

- Stutter

- Then sit there humming with reversing torque cancelling itself out

- A quick sanity check when you see a drawing:

- No gaps, one continuous smooth ring per circuit? → Slip ring.

- Visible segments with insulation between them? → Commutator.

- Arrows showing current reversing every half turn? → Definitely a commutator diagram.

- No gaps, one continuous smooth ring per circuit? → Slip ring.

11. Practical design & selection tips

When you’re choosing or specifying these parts, think beyond “does it fit on the shaft?”.

For slip rings, focus on:

- Signal integrity – Is this carrying high-speed data or just power?

- Current density – Brush material and ring width must support your amps.

- Environment – Is it in a wind turbine nacelle, medical scanner, or clean lab?

- Maintenance strategy – Do you have access for brush replacement, or do you want “fit-and-forget” with precious-metal contacts?

For split-ring commutators, focus on:

- Compatibility with brush grade – Wrong combination = excessive sparking.

- Segment count and pitch – Tied directly to torque ripple and performance.

- Surface quality – Out-of-round commutators wreck brushes and produce noise.

- Cooling – Large DC machines can waste serious heat in the commutator region.

- A useful rule when in doubt:

- If a modern electronic drive can easily do the polarity-changing for you, consider a brushless design and a slip ring or even wireless link instead of a commutator.

- If your application is constrained to simple, robust DC motors or generators without sophisticated electronics, you’ll be living with a commutator – so design for easy service.

- If a modern electronic drive can easily do the polarity-changing for you, consider a brushless design and a slip ring or even wireless link instead of a commutator.

12. Quick FAQ

Q: Can I replace a split-ring commutator with slip rings plus an electronic inverter?

In principle, yes. That’s exactly what brushless DC motors and many modern AC drive systems do: use electronics to handle commutation instead of a mechanical commutator. But that’s not a drop-in replacement – it’s a redesign of the entire machine and control strategy.

Q: Do slip rings always handle AC and commutators always handle DC?

Not exactly. Slip rings can carry AC or DC just fine; they don’t care about waveform. Commutators are about reversing current in DC machines – they can “see” AC-like waveforms in the rotating frame, but what you get at the terminals is more DC-like.

Q: Why do commutators spark more than slip rings?

Because they switch current: every time the brushes cross a segment gap, current is broken or redirected while inductive windings fight the change, which encourages arcing. Slip rings, by contrast, ideally maintain continuous contact without intentional breaking.

Q: In an AC generator drawing, I see two rings and two brushes. Are those split rings?

No – those are almost always slip rings, because an AC generator wants the full sinusoidal output, not rectified DC. If you see many segments instead of two smooth rings, then you’re likely looking at an AC machine feeding a commutator to deliver DC externally.