Sensorless Commutation: Getting BLDC Drives Past The Lab

Sensorless commutation is largely solved on paper. Back-EMF schemes, observers and injection tricks all work. What still kills projects is not lack of theory but measurement details, start-up behavior, and how the algorithm degrades at the edges. Treat those as first-class design problems and almost any modern method will reach your spec. Ignore them and you get random resets, hot MOSFETs, and support tickets.

Table of Contents

What most articles gloss over

If you read typical sensorless control content, you usually get the same pattern: define BLDC, compare sensor vs sensorless, show a neat back-EMF diagram, then point at one or two algorithms. Some app notes go deeper into filtering and virtual neutral points, but still stop where the hardware and firmware start arguing with each other.

Recent work and vendor notes do push further: terminal-voltage commutation without neutral sensing, filterless DC-link schemes, sliding-mode observers, high-frequency injection, even neural-network estimators. But they are usually described as choices on a menu, not as pieces in a production-grade chain that has to share silicon, bandwidth and EMC limits.

So this is not a tutorial. It is a field-biased view of what actually decides whether your sensorless commutation is boringly reliable or permanently “under investigation.”

Two problems hiding under “sensorless commutation”

You never really design “sensorless commutation” as a single block. You design two separate regimes and an arbitration layer that pretends they are the same.

At zero and very low speed, back-EMF is not measurable. Classical zero-cross schemes and most back-EMF observers are blind here. You either run open-loop (forced commutation with an assumed rotor position), you inject a probing signal, or you live with an awkward speed floor.

Once the rotor is moving fast enough, the problem changes character. You are no longer asking “where is the rotor at all?” but “how late is my estimator and how stable is it over current, temperature, and supply?” In this region, almost every sensible algorithm works if the signals are clean. The differentiator is how predictable the delay and failure modes are.

The handover between these regimes is where many systems misbehave. A common anti-pattern is to glue a crude open-loop ramp to a sophisticated high-speed estimator and assume a single speed threshold will keep them out of each other’s way. It tends to work on the bench, then fail at odd combinations of load and supply voltage that your test plan did not cover.

Choosing a method: not just “FOC vs six-step”

Most blog posts frame the choice as a binary: block commutation with simple back-EMF sensing, or full field-oriented control with some observer. Vendors publish clear comparisons on torque ripple, noise and efficiency. Reality is more granular.

Here is a compact view of the main families actually used today, including techniques that appear in recent papers and newer app notes.

| Method | Typical sweet spot | Required signals / hardware | Main practical pain points | Where it tends to win |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple back-EMF zero-cross with virtual neutral | Medium to high speed, trapezoidal motors | Phase voltages, virtual neutral network, comparators or ADC | Poor low-speed performance, sensitive to supply ripple and motor tolerances, tuning of RC filters vs speed | Fans, pumps, low-cost drives where acoustic noise and dynamic response are not strict |

| Filtered back-EMF with digital timing logic | Medium to high speed, wider RPM span | ADC sampling of phase voltages, digital filters, timer capture | Speed-dependent phase delay of filters, calibration across motors, computational budget on small MCUs | Cost-sensitive drives needing better timing accuracy than raw comparator schemes |

| Line-to-line / terminal-voltage commutation | Medium speed, low-voltage BLDC | Two or three terminal voltages referenced to DC bus, usually no neutral reconstruction | Layout-dependent coupling, need for good common-mode rejection, careful timing of measurement windows | Compact low-voltage drives where PCB area and BOM for neutral networks or filters is constrained |

| Filterless DC-link modulation methods | Medium speed, low-voltage systems with noisy PWM | DC-link voltage and current, special modulation pattern | Tied to a specific modulation; retrofit to generic inverter firmware is awkward; interaction with EMI filters | Cases where PWM noise dominates and eliminating analog filters saves both cost and commutation delay variation |

| Sliding-mode or observer-based back-EMF estimation | Wide speed range above some low-speed floor | Phase currents and voltages, computationally heavier estimator | Chattering control, parameter sensitivity, debugging complexity, need for fixed-point care on small MCUs | Higher-end drives needing continuous position estimates, better dynamic response, and FOC compatibility |

| High-frequency injection (HFI) and saliency-based methods | Zero to low speed, especially IPMSM with saliency | High-frequency voltage injection and current measurement, good analog front end | Acoustic noise from injection, parameter dependence on temperature, more math, EMI considerations | Servo-style applications requiring torque at standstill without sensors, or drives that must start under unknown load reliably |

| Data-driven / ML-assisted estimators | Varies; mostly in research and niche products | More memory and compute, training data or adaptation loop | Harder to certify and explain, sensitivity to unseen operating points, maintenance of models | Custom drives where you can collect field data and want to compensate strongly nonlinear effects or manufacturing spread |

The point is not that one row is “best.” It is that most real products end up mixing at least two of these behaviors over speed, sometimes three. For instance, a moderate-end appliance drive may use open-loop alignment and ramp, then a line-to-line commutation scheme, and finally transition into full FOC with a back-EMF observer once the speed and SNR make it worthwhile.

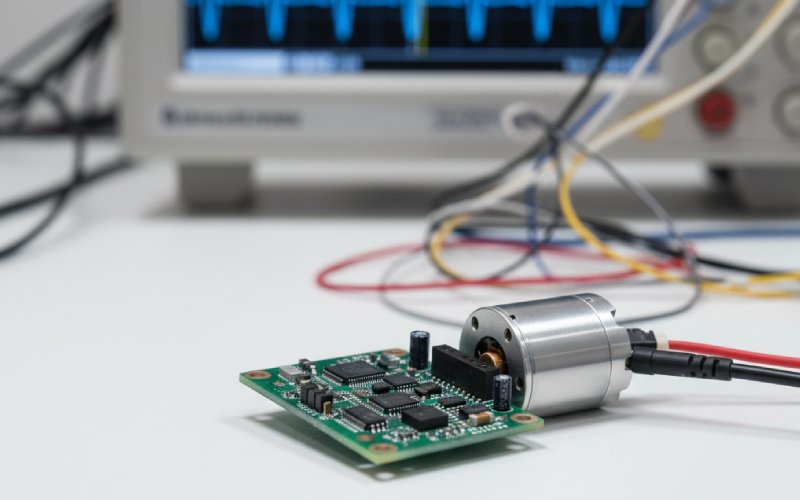

Measurement plumbing decides almost everything

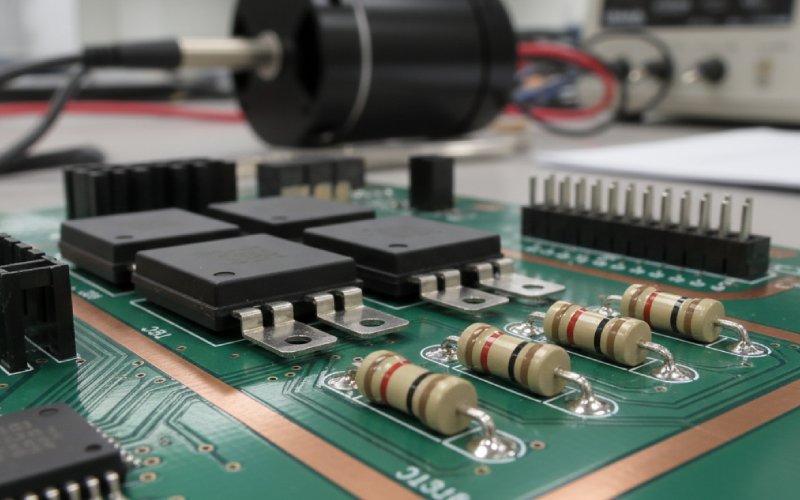

Papers and marketing material usually show clean phase waveforms with polite slopes. Your PCB will not. The whole sensorless stack stands on what the ADC or comparator actually sees after dead time, diode recovery spikes, supply ripple, ground bounce and cheap shunts.

A few patterns show up repeatedly.

If you use comparators for zero-cross detection, hysteresis and blanking times are not minor settings. They directly program how much electrical degrees of timing error you tolerate at different speeds. Too little hysteresis and the comparator chatters on PWM edges. Too much and the effective crossing threshold drifts with current. Blanking that hides switching edges may also hide the true zero crossing at high speed. Vendors hint at this, but tuning still tends to be trial-and-error unless you explicitly budget phase error over your entire speed and current range.

If you rely on ADC sampling of back-EMF, the interaction between sampling instants and PWM patterns becomes the core problem. Center-aligned PWM, edge-aligned PWM and space-vector modulation all create different “clean” windows for measuring a floating phase. Shift the sampling ISR by just a few CPU cycles and you change your estimator bias. Most “it works in one build but not in another” stories trace back to this timing coupling rather than mistakes in the algorithm equations.

For observers used with FOC, current sensing quality quietly sets your commutation quality too. Offset drift in shunts, poor reconstruction in single-shunt designs, or saturated amplifiers during current spikes all leak straight into the estimated rotor position. That then looks like torque ripple or acoustic noise and easily gets misattributed to the modulation strategy.

So if you want a practical rule: treat the analog front end and sampling schedule as part of the commutation algorithm, not as plumbing. Draw them on the same diagram. Write down their delays in electrical degrees at several speeds and currents. Adjust code until the numbers are explicit, not guessed.

Start-up and low speed: choosing your fiction

At standstill you must make a decision: either you assume a rotor position and enforce a pattern, or you disturb the motor and read its response. Both are approximations. The question is which approximation fails more gracefully in your application.

Open-loop alignment and ramp is simple and cheap. You energize a known vector long enough to pull the rotor into alignment, then accelerate commutation at a fixed profile until back-EMF or an observer has enough signal to take over. This works well when the load torque is predictable and the inertia is known. It becomes fragile when the load can block, reverse, or apply a step torque at start. In that case, the rotor may not follow the assumed trajectory and you have no way to know until you either hit current limits or the estimator suddenly disagrees.

High-frequency injection methods deliberately avoid that fiction by treating the low-speed motor as a quasi-static magnetic system. A small probing signal reveals rotor saliency or anisotropy, which gives you a position estimate even with zero average speed. This improves low-speed torque control and start-up robustness but adds a constant background of injected energy and algorithm complexity. You also need to accept that acoustic and EMI signatures change; sometimes that is fine, sometimes marketing will call it a problem.

A hybrid design often works best: short deterministic alignment, minimal open-loop ramp, then HFI only in the narrow region where back-EMF based estimation is not yet comfortable. Discontinuous use of injection reduces acoustic impact and computation, yet still gives the estimator something to hold onto through awkward transients like slow cranking or partial stalls.

Timing error, not algorithm name, drives losses and noise

Discussions around efficiency and acoustic performance often compare six-step control to FOC as if commutation style alone set the outcome. In practice, the dominant factor is phase alignment error between rotor flux and current, not whether your code writes three duty cycles or two plus a zero vector.

With basic block commutation, any consistent timing error on the commutation instants pushes the torque ripple and increases copper and core losses. Under-advanced commutation wastes potential torque and produces a characteristic growl at certain speeds and loads. Over-advance increases current for the same load and can heat the motor and inverter disproportionately. The same logic applies in continuous FOC, just expressed as an angle error in the observer or encoder.

That is why the specifics of your sensorless estimator matter less than their variance and bias across operating points. A crude zero-cross scheme with carefully characterized delay and a simple speed-dependent advance table can deliver better real efficiency than a sophisticated observer that shifts by several degrees whenever the DC bus jumps because a compressor kicked in.

So one concrete target is to quantify your electrical angle error over load, speed, and bus voltage. If you can keep it within a narrow band that you know, you can compensate. If you cannot even measure it, you are just swapping algorithms and hoping.

Using newer ideas without rebuilding the whole stack

Recent publications on sensorless commutation bring techniques that can be used incrementally rather than as total replacements.

Filterless DC-link modulation methods show that you can avoid classic RC filters and still achieve clean commutation instants by shaping the inverter switching to simplify what you measure. You do not have to copy the modulation exactly to learn from this; even modest constraints on switching patterns in certain sectors can make your measurement windows more predictable and reduce dependence on analog filters.

Terminal-voltage based commutation, including schemes that only use two terminal voltages relative to a virtual neutral, can reduce component count and sometimes improve tolerance to common-mode disturbances. It also forces you to think of the motor and inverter as a single distributed network, because layout-dependent capacitances suddenly affect your sensing directly. That is less comfortable but gives you a more honest model.

Sliding-mode observers and similar robust techniques are often presented as all-or-nothing components, yet they can coexist with simpler estimators. One pragmatic pattern is to run a basic back-EMF estimator and a more advanced observer in parallel, then use confidence logic to pick which one feeds the commutation angle at each operating point. This is especially useful when your advanced estimator is strong under dynamic load but less trustworthy near specific combinations of speed and DC bus ripple.

Machine-learning based estimators are still young in this area, but some work already combines terminal voltages and DC-link variables to drive neural models for commutation timing. Even if you never ship a neural estimator, offline models trained on lab data can help you understand the structure of your phase errors and design better rule-based compensation.

A practical tuning path that does not chase ghosts forever

On a new design, it is tempting to bring up the full sensorless stack at once. That usually masks problems rather than saving time. A calmer route uses staged complexity and hard logging.

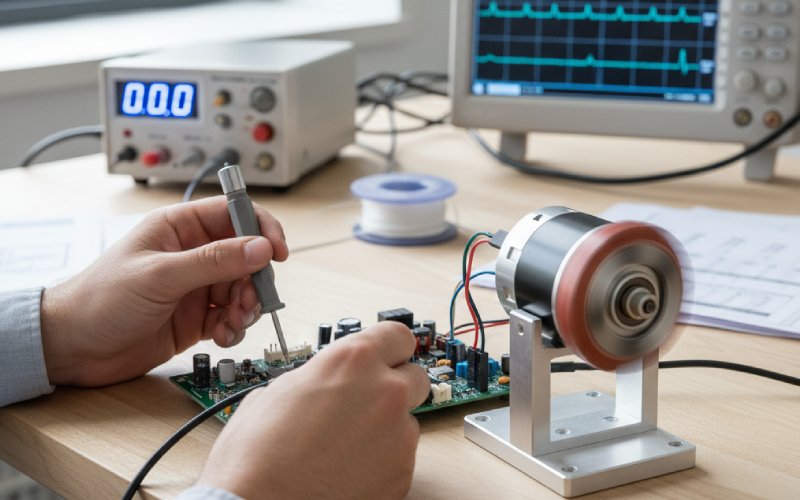

First, make the inverter and current sensing boring with sensored control or a known good open-loop pattern. Verify that current readings, temperatures, and EMI behavior match expectations. If this step is weak, any sensorless method will inherit that weakness and amplify it.

Second, implement the simplest possible commutation detection method that can run on your hardware, even if you know it will not meet the final requirements. For many systems, that is raw comparator zero-cross detection with fixed delays. For others, it might be a basic back-EMF ADC estimator with no fancy filtering. Use it to collect angle error data against an external reference such as an encoder or a temporary Hall sensor ring.

Third, from that data, build speed-dependent and load-dependent correction tables or compact models. Only after you can explain the shape of those corrections does it make sense to introduce observers, digital filters, or hybrid schemes. Otherwise you are just stacking compensators blindly.

Finally, treat transitions as first-class features. Define exactly at which speed and conditions you switch from open-loop to estimator A, from estimator A to estimator B, or from six-step to FOC. Log those transitions explicitly and stress them in testing: bus jumps, sudden load steps, reverse commands, brown-outs.

None of this is exotic. It is just methodical. And it tends to produce drives that behave the same on Monday and Friday, on hot and cold units, across production spread.

Debugging by symptoms instead of by theory

In practice, you usually start from motor behavior, not from equations. Certain symptoms map strongly to certain classes of sensorless commutation issues. A few examples illustrate the mindset.

If the motor starts reliably when cold but refuses when warm, suspect temperature-dependent shifts in comparator thresholds, shunt offsets, or motor parameters used in observers. You can verify this by logging estimated angle against an encoder as the system warms from ambient to its steady state.

If the drive is quiet and efficient at low and high speed but has a narrow noisy band in the mid-range, suspect speed-dependent filter delays, timer quantization, or PWM interaction. Back-EMF based methods that rely on RC networks and timers often show such “noisy bands” where their fixed delay assumptions line up badly with motor electrical frequency.

If the drive behaves well under steady load but misfires during rapid torque steps, look at observer bandwidth and current sensing saturation. Many sliding-mode or PLL-based estimators assume current signals stay within linear ranges and that sampling jitter is modest. When those assumptions break, the estimator lags, and commutation angle can jump several degrees.

Having a catalog of such symptom-to-mechanism pairs inside your team often shortens debugging more than yet another new estimator.

Closing notes

Sensorless commutation does not need another generic explanation of back-EMF. It needs an honest view of what really decides whether the drive is stable, efficient, and reproducible across a production line. Algorithms matter, but the combination of measurement chain, start-up strategy, transition logic, and explicit timing error budgets matters more.

If you design those parts as deliberately as you pick the estimator, most of the classic debates about six-step versus FOC, or back-EMF versus observers, become much less dramatic. You end up with a system whose commutation behavior is predictable, explainable, and only as complex as your application actually needs.