Purpose of a Commutator in a DC Motor: The Tiny Switch That Makes Everything Spin

If you stripped a DC motor down to its bones and asked, “What’s the one part that quietly makes this whole thing work?” — the commutator would raise its little copper hand.

Most textbook-style articles will tell you, “The commutator reverses current to keep torque in one direction.” That’s true… but it’s like saying, “Lungs are for breathing” and stopping there. In this guide, we’ll go a lot deeper — into what a commutator really does, why it’s designed the way it is, and how it shapes the behavior, control, and lifespan of a DC motor.

Table of Contents

At a glance: what the commutator does (in plain English)

- Feeds current from a stationary DC source into a spinning rotor

- Flips the direction of current in the rotor coils at just the right moments

- Keeps torque pushing in one direction instead of making the shaft jerk back and forth

- Helps the motor deliver smooth speed, neatly controlled by voltage and load

- Acts as an electromechanical “wave-shaper”, turning a simple DC supply into the alternating current pattern the armature actually experiences

What is a commutator, really?

Imagine a tiny, automatic electrician riding on the motor shaft, constantly swapping wires over as the rotor spins, making sure each coil is always “pushed” the right way by the magnetic field. That’s the commutator’s job.

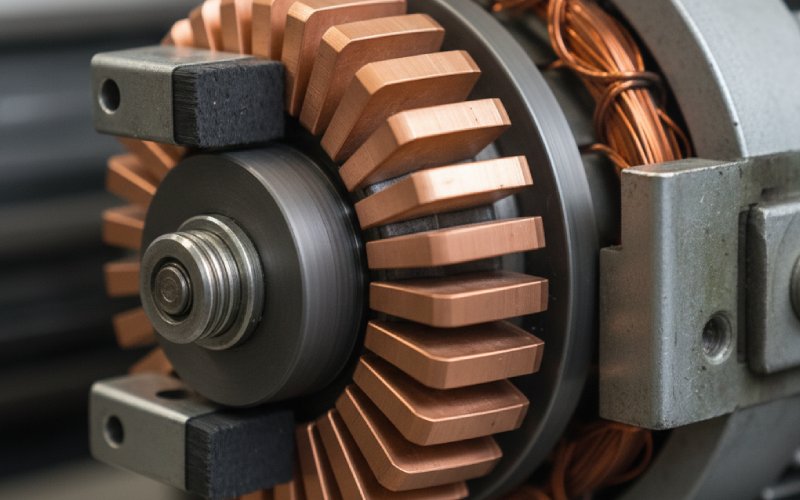

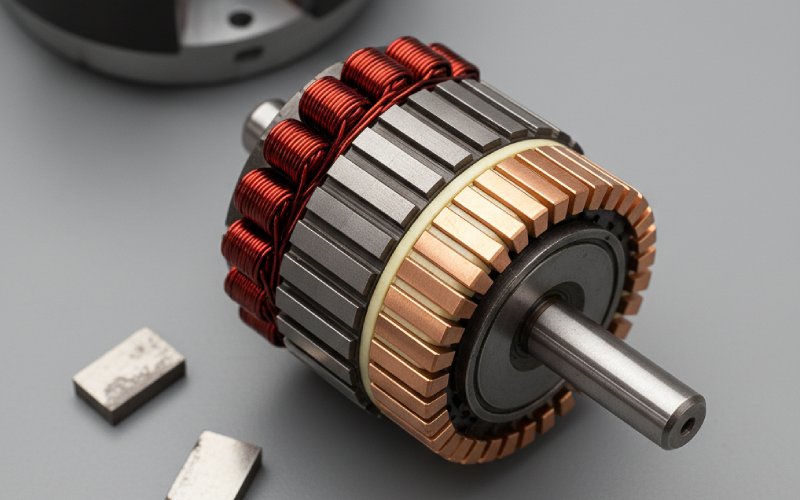

Technically, a commutator is a rotary electrical switch made of multiple copper segments arranged around the rotor shaft. Each segment is connected to specific armature (rotor) windings and insulated from its neighbors (typically by mica). Fixed carbon brushes press against these segments to bring power in from the outside world.

Key construction features (and why they matter)

- Segmented copper cylinder

- Each segment connects to one or more armature coils

- Segmentation is what allows the “switching” of current direction as the rotor turns

- Insulation between segments (often mica)

- Prevents short-circuits between segments

- Withstands heat and mechanical stress over long runs

- Mounted on the rotor shaft

- Spins with the armature so the connections change relative to the brushes

- Carbon brushes pressed against the commutator

- Provide a sliding electrical contact from stationary terminals to rotating segments

- Carbon is used because it’s conductive yet sacrificial and self-lubricating

All of that “plumbing” is in service of one big goal: control the current in the rotor windings so that the magnetic forces always produce useful rotation.

The physics story: why do we need current reversal?

In a DC motor, the rotor coils sit in the magnetic field of the stator (either permanent magnets or field windings). When current flows through these coils, each becomes a tiny electromagnet. The stator field pushes and pulls on these electromagnets, producing torque that tries to turn the rotor.

But here’s the catch:

As each coil rotates, the direction of the force it experiences changes. If we didn’t do anything clever, the torque would reverse direction every half turn, and the rotor would just rock back and forth instead of spinning continuously.

That’s where the commutator steps in: it reverses the current in each coil exactly when that coil passes the “neutral” position, so the torque keeps pointing in the same rotational direction.

How the commutator “flips” current each half turn

- The armature coil ends are connected to two opposite commutator segments

- Two brushes press on the commutator, connected to the DC supply

- As the rotor spins, each brush slides from one segment to the next

- Just as a coil passes through the neutral plane, its connections swap from “+” to “–” (or vice versa)

- The coil’s current direction reverses in sync with its position, so the torque on that coil does not reverse

Think of it like flipping the polarity of each electromagnet right when it would otherwise start pulling the wrong way.

Core purposes of the commutator in a DC motor

1. Maintain unidirectional torque (keep the shaft spinning, not rocking)

The primary purpose of the commutator is to ensure that the motor’s torque always pushes in the same rotational direction. By reversing the current in each armature coil at the right time, the commutator guarantees that the electromagnetic forces always “line up” to turn the rotor forward.

Without that timed reversal, a DC motor would behave more like a fussy pendulum than a smooth drive.

- Reduces torque ripple, making rotation smoother

- Avoids “dead spots” where the net torque would otherwise fall close to zero

- Enables reliable starting torque from standstill (with correct brush positioning)

2. Act as the electrical interface between static and rotating parts

You can’t bolt wires directly onto a spinning rotor — they’d twist off in a few seconds. The commutator solves this elegantly: it acts as a rotating terminal block, and the brushes act as sliding connectors from your DC supply to the rotor windings.

In practice, this means:

- You can feed steady DC into a machine whose core current pattern is actually constantly changing

- You get a clean path for current into many different coils, with the commutator controlling which coils are energized at each angle

- You can safely mount power electronics, controllers, and wiring in the stationary housing while the rotor spins freely

Why this interface matters day-to-day

- Allows compact, high-torque motors in tools, toys, actuators, and automotive systems

- Simplifies wiring and control — just apply a DC voltage at the terminals and the commutator + brushes handle the rest

- Enables easy direction reversal: swap supply polarity, and the commutator simply “mirrors” that change in the armature

3. Shape the hidden “AC world” inside a DC motor

From the outside, you feed a DC voltage into the motor. But inside, thanks to the commutator, the current in each coil actually alternates as the rotor turns. To the armature windings, the commutator is effectively:

A mechanical AC generator and rectifier rolled into one, shaping how current flows in time.

In DC generators, the commutator’s role is to rectify the AC induced in the armature into DC at the terminals. In DC motors, it does the complementary job: it takes DC at the brushes and produces a sequence of current reversals in the rotating coils.

- This waveform-shaping is critical for efficient electromagnetic interaction

- It keeps the magnetic fields properly oriented for maximum torque

- It allows relatively simple, low-frequency control (change DC voltage → change speed)

4. Enable speed and torque control in real applications

One of the big selling points of DC motors is that they’re easy to control: speed roughly tracks applied voltage, and torque follows current. The commutator quietly supports that simplicity.

With a good commutator:

- Speed can be smoothly regulated over a broad range just by adjusting voltage

- Direction can be reversed by swapping polarity, and the commutator keeps the internal current pattern consistent with that change

- Motors can deliver steady torque under varying load, because the commutator keeps refreshing which coils are doing work at each angle

In practice, this is why DC motors with commutators are used in:

- Power tools (drills, saws, grinders)

- Automotive systems (wipers, seat motors, window lifts, starters in older designs)

- Industrial drives and small actuators that need good low-speed torque and simple control

5. Commutator vs. “no commutator”: what actually changes?

Here’s a side-by-side view of what the commutator is really buying you:

| Aspect / Purpose | Without a Commutator | With a Commutator |

| Torque direction | Reverses every half turn → shaft rocks, not spins | Kept effectively unidirectional → continuous rotation |

| Current in rotor coils | Fixed direction relative to supply | Reversed in sync with rotor angle |

| External supply type | Needs more complex switching or AC linkage | Simple DC supply at brushes |

| Interface between stator and rotor | Twisted wires or complex slip arrangements | Robust brush–commutator system |

| Motor speed control | Harder; needs external electronics for commutation | Change DC voltage, motor speed follows relatively smoothly |

| Generator operation (same hardware) | Outputs AC directly | Commutator rectifies internal AC into DC at terminals |

| Maintenance | Less mechanical wear but more electronic complexity | Some wear at brushes/segments; simpler electronics |

| Typical applications | Brushless DC, induction, synchronous machines | Brushed DC motors, universal motors, many legacy machines |

The commutator is essentially a trade-off: more mechanical complexity and wear, in exchange for simpler electronics and very intuitive control.

6. How the commutator differs in DC motors vs DC generators

Even though DC motors and DC generators can often be built from almost the same physical machine, the commutator’s role is viewed slightly differently:

- In a DC motor

- Feeds DC into the brushes

- Commutator ensures armature coils see alternating current direction appropriate for continuous torque

- Seen as providing current to armature conductors and “converting” the external DC into the internal AC pattern

- In a DC generator

- Armature conductors generate AC as they cut the magnetic field

- Commutator acts as a rectifier, flipping connections so output at the brushes is DC

- Collects the current from the armature and delivers it as a usable DC output

Same copper cylinder, different viewpoint: in one case it’s “feeding” the armature; in the other, it’s “harvesting” from it.

7. Commutator vs slip rings: why DC motors don’t use slip rings

Slip rings and commutators both let you connect to spinning parts, but they aren’t interchangeable.

- Slip rings

- Smooth, continuous rings

- Provide a constant connection (no switching)

- Common in AC machines where the rotor current need not be reversed by mechanical means

- Commutators

- Segmented rings

- Intentionally switch which segment is connected to which brush

- Used in DC motors to reverse the polarity of current in rotor windings and maintain unidirectional torque

If you replaced a commutator with slip rings in a DC motor, you’d lose the timed current reversal and the motor would no longer produce sustained unidirectional rotation without extra electronics.

8. How the commutator’s purpose shapes its design and maintenance

Because the commutator is doing high-stakes work — switching significant current at high surface speed — its design and condition have a huge impact on motor performance.

A few practical consequences of its role:

- Segment geometry and material

- Copper segments must handle high current density and stay smooth to avoid arcing and excess wear

- Insulation (often mica) must endure both heat and mechanical abrasion

- Brush material and pressure

- Brushes must make solid electrical contact without destroying the commutator surface

- Too little pressure → sparking and poor commutation

- Too much pressure → overheating and rapid wear of both brushes and commutator

- Commutation quality

- The timing of reversal (brush position vs magnetic neutral plane) affects sparking

- Poor commutation can cause:

- Visible sparking

- Excessive brush wear

- Radio interference

- Local overheating of segments

- Maintenance philosophy

- Regular inspection, brush replacement, and commutator resurfacing (turning/polishing) extend motor life

- Design choices (more segments, higher-quality materials) reduce stress on each switching event, improving performance at higher speeds and loads

9. Bringing it all together

The commutator isn’t just “that copper thing with brushes.” In a DC motor, it is:

- The mechanical brain that decides which rotor coils are energized and in which direction

- The bridge between a quiet, steady DC supply and a violently spinning electromagnetic machine

- The timing mechanism that keeps torque marching in a single direction, turning jerky forces into smooth rotation

It reverses current at precisely the right moments, maintains contact between the stationary and rotating parts, shapes the internal current waveforms, and enables straightforward speed and torque control — all at once.