Purpose of Commutator in a Motor: A Deep, Human-Friendly Guide

If you’ve ever seen the inside of a brushed DC motor, you’ve probably noticed a shiny segmented cylinder with dark blocks rubbing against it. That little copper-and-carbon drama at the end of the shaft is the commutator, and without it your “motor” would spin a bit, shrug, and then give up.

In this guide, we’ll go past the one-liner (“it reverses current”) and build a real mental model of what the commutator is doing, why motors need it, and how it compares to modern brushless designs.

- In one sentence: The commutator is a mechanical switching system that flips the direction of current in the rotor windings at exactly the right moments so the motor’s torque keeps pushing in the same rotational direction.

- It turns incoming electrical power into properly timed current inside the spinning coil.

- In a DC motor, it keeps the rotor moving instead of stalling when the magnetic fields line up.

- In a DC generator, it acts as a mechanical rectifier, turning internally generated AC into DC at the output.

- It’s also the reason brushed motors need maintenance (brush wear, sparking, dust, etc.).

Table of Contents

1. What is a commutator, physically?

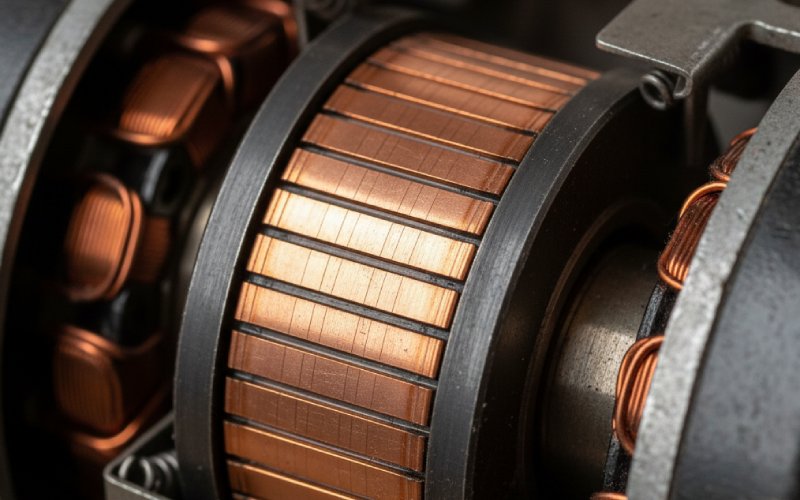

Let’s zoom in on the rotor shaft. On a typical brushed DC motor, the commutator is:

- A cylindrical ring of copper broken into many insulated segments.

- Fixed on the rotor (armature), rotating with it.

- Connected internally so each segment leads to one end of a coil in the rotor winding.

On the stationary side, you have brushes (usually carbon) pressed against the commutator by springs. As the rotor spins, the brushes slide from one segment to the next, maintaining electrical contact with different coils over time.

This sliding contact looks crude compared to a smooth electronic switch, but it’s incredibly clever: the geometry of the segments and brush positions encode the timing of current reversal directly into the mechanics of the motor.

- Core pieces in a brushed DC motor:

- Stator: produces a (roughly) fixed magnetic field.

- Rotor / armature: rotating iron core with coils of wire.

- Commutator: segmented copper ring wired to rotor coils.

- Brushes: stationary conductive blocks that feed current into the commutator.

- Power source: typically DC supply (battery, DC bus, etc.).

2. The core purpose in a DC motor: keep torque pushing the same way

Think of the rotor coil as a tiny bar magnet that appears whenever you run current through it. The stator provides a fixed magnetic field. When you energize the rotor coil, the magnetic forces try to:

- Align the rotor’s magnetic field with the stator’s field (like two bar magnets snapping together).

At first, this alignment force makes the rotor start to turn. But here’s the catch:

- Once the rotor lines up with the stator field, the torque goes to zero — the motor would naturally stall right there.

To avoid that stall, the motor must do something sneaky: flip the direction of current in the rotor coil right as it passes the neutral position. That flips its magnetic polarity, so instead of settling comfortably, it’s again pushed into rotation – over and over.

That “flip at just the right time” is the commutator’s entire reason for existing. It ensures the torque stays essentially unidirectional (always pushing the rotor around instead of letting it lock in place).

- In a DC motor, the commutator’s purpose can be described as:

- Reversing the current in each rotor coil every half turn.

- Making sure the electromagnetic torque always acts in the same rotational direction.

- Turning a simple DC input into a properly alternating current pattern inside the rotor (from the rotor’s point of view, it actually sees a kind of AC).

- Preventing the rotor from stalling when its magnetic field lines up with the stator field.

3. Motor vs Generator: the commutator’s two personalities

Many sources explain commutators using both motors and generators, which can feel confusing. Let’s align that clearly:

Inside both machines, the armature windings naturally see AC as the rotor spins through a magnetic field. The commutator decides how that looks externally.

Here’s a simple comparison:

| Machine type | What the armature “naturally” produces or sees | What the commutator does | How textbooks often phrase it |

| DC Motor | Rotor windings need their current flipped as they move under alternating poles | Swaps which coil ends connect to + and – every half turn, so current in each active coil reverses | “Maintains unidirectional torque by reversing current in the armature windings.” |

| DC Generator | Coils cutting the magnetic field generate an AC voltage internally | Flips connections so the external terminals see current in one direction only | “Acts as a mechanical rectifier to convert AC to DC at the output.” |

So:

- In a motor, the commutator’s job feels like a “mechanical inverter” (turning external DC into alternating current in the spinning coils).

- In a generator, it behaves like a “mechanical rectifier” (turning internally generated AC into DC at the terminals).

Same hardware, opposite viewpoint, same core idea: timed polarity reversal.

- Mentally, you can think of the commutator as:

- A rotary polarity flipper that’s synced perfectly with rotor position.

- A hard-coded timing system that doesn’t need sensors or microcontrollers.

- A way to get DC at the terminals while still leveraging the natural AC behavior of rotating coils.

4. How the commutator actually works, step by step

Let’s walk through one simple two-pole DC motor with a single active coil:

- The coil sits between north and south poles of the stator.

- The brush on the positive terminal touches a commutator segment connected to one end of the coil; the negative brush touches the opposite segment.

- Current flows through the coil in a certain direction → creates a rotor magnetic field.

- The torque pushes the rotor and the coil starts rotating.

- Just as the coil passes the neutral zone (where torque would drop), the brushes slide onto the next pair of segments.

- That switching reverses which coil end is connected to + and – → current in the coil reverses.

- Because the physical coil also rotated 180°, this polarity flip keeps the direction of torque the same as before.

With more coils and more commutator segments, you get smoother torque and less “cogging” because at any moment several coils are contributing overlapping torque pulses.

- Key outcomes of this switching dance:

- Continuous rotation instead of rocking back and forth.

- Nearly steady torque, especially in multi-segment machines.

- Ability to control speed and torque fairly simply by adjusting supply voltage or armature current.

- The possibility to use the same machine as both motor and generator, just by changing how it’s driven.

5. Why DC motors need commutators (and induction motors don’t)

You might wonder: “AC motors don’t seem to need commutators—what’s different?”

- In a brushed DC motor, the stator field is usually fixed in direction (from permanent magnets or DC field windings). To keep the rotor turning, something must reverse the rotor current – that’s the commutator.

- In an AC induction or synchronous motor, the stator itself creates a rotating magnetic field using AC. The rotor doesn’t need a commutator because the torque direction is handled by the stator’s rotating field rather than by flipping the rotor current with brushes.

There’s also a third family: commutator-type AC motors (universal motors). They still use a commutator, but the current is AC; the field and armature currents reverse together each half-cycle, keeping the torque unidirectional.

- High-level comparison: commutator vs slip rings:

- Commutator

- Segmented copper ring.

- Reverses current direction in the rotor coils at specific angles.

- Used mainly in DC motors/generators and some universal motors.

- Slip rings

- Smooth continuous rings.

- Provide a continuous electrical connection without flipping polarity.

- Used in AC machines (like AC generators) and for transferring power/signals to rotating parts.

- Commutator

6. Real-world design + limitations of commutators

Engineers don’t just throw in a couple of copper chunks and call it a day. Commutators are carefully designed systems:

- A practical commutator has many segments, not just two. That reduces torque ripple and allows smoother operation.

- Brushes are deliberately wider than the insulating gaps between segments so they always touch at least one live segment. This avoids “dead spots” where the motor might not start.

- Segments are insulated with materials like mica or plastics and mechanically locked to the shaft so they survive temperature changes and centrifugal forces.

But the same mechanism that does this beautiful timed switching also introduces compromises:

- Friction: sliding contact means energy is lost as heat at the brush–commutator interface.

- Wear and dust: brushes wear down and produce carbon dust, which can contaminate the machine.

- Voltage drop (“brush drop”): the contact resistance steals a few volts, which matters a lot in low-voltage, high-current applications.

- Sparking and EMI: switching and contact bounce can create arcs and electrical noise, problematic in explosive or sensitive environments.

These issues are exactly why very large or maintenance-critical machines almost always use AC or brushless DC designs instead of big commutated DC machines.

- Typical trade-offs when you choose a commutated motor:

- ✅ Simple speed control with DC voltage.

- ✅ High starting torque, great for tools and appliances.

- ❌ Brush maintenance (limited life, replacement required).

- ❌ Not ideal for dusty-free, sealed, or explosive environments.

- ❌ Efficiency limits due to friction, voltage drop, and sparking.

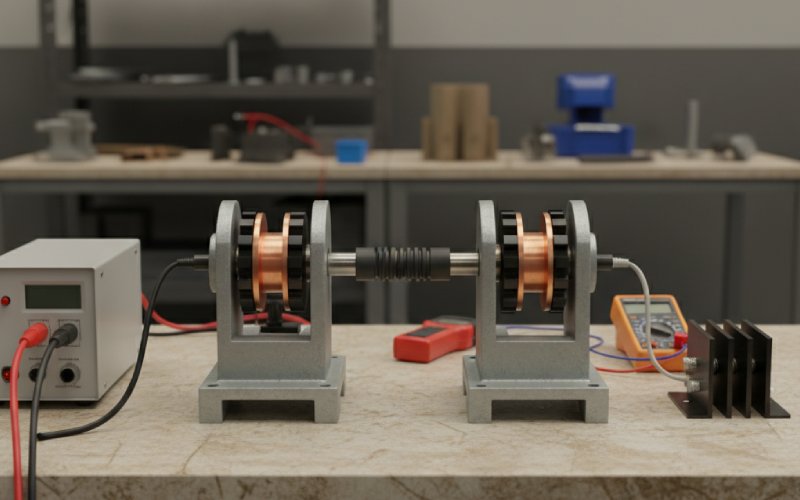

7. Enter brushless DC motors: electronic commutators

Modern systems often replace the mechanical commutator with electronics:

- In a brushless DC (BLDC) motor, the rotor holds permanent magnets and the stator contains the windings.

- Instead of brushes and a copper commutator, we use sensors (or sensorless algorithms) plus power electronics (transistors) to switch currents in the stator at precisely the right rotor angles.

- Functionally, the electronics act as a digital commutator: they still flip currents at specific angles to maintain unidirectional torque, just without sliding contacts.

So the purpose hasn’t disappeared—only the implementation changed.

- Why brushless is displacing brushed commutator motors in many applications:

- Much lower maintenance: no brushes to replace.

- Higher efficiency: reduced losses from friction and brush drop.

- Better control: easy integration with digital control, precise speed/torque regulation.

- Longer life: usually limited by bearings rather than brushes/commutator wear.

8. A clean mental model to keep

If you remember only one picture, use this:

The commutator is a rotating, position-synchronized polarity switch that makes sure the electromagnetic “push” on the rotor never reverses, even though the rotor itself keeps turning through 360°.

In motors, that means continuous torque and rotation. In generators, that means DC at the terminals from inherently AC processes inside.

Everything else—the copper segments, carbon brushes, sparks, and maintenance—are the practical side effects of implementing that one elegant idea in metal instead of code.