Mechanical commutator vs electronic/magnetic commutation in DC motors

If you are choosing a commutation method today, mechanical commutators are usually a cost hack, not a performance feature. Electronic or magnetic commutation gives better efficiency, cleaner signals, longer life and more control options, and you only stay with brushes when the electronics budget, life expectations or regulatory environment are very forgiving.

Table of Contents

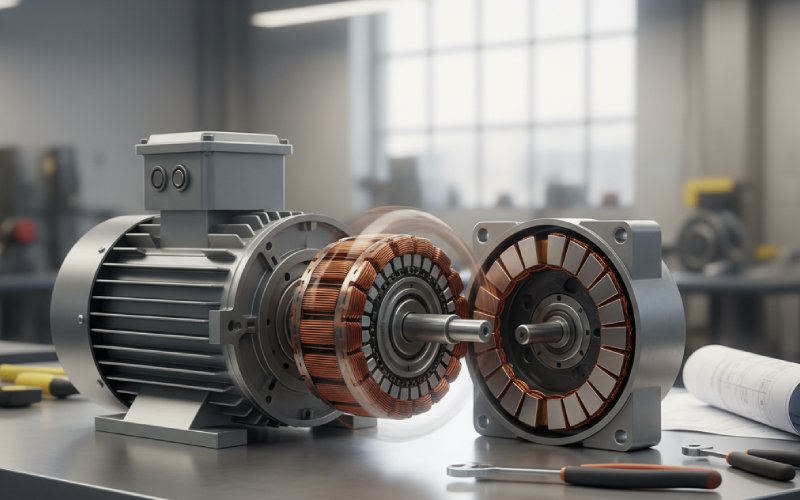

What actually changes when you remove the mechanical commutator

Both approaches chase the same objective: keep the torque-producing magnetic fields in a useful relative angle as the rotor spins. The difference is where you pay for the switching and where the wear and risk live.

In a mechanically commutated DC motor, copper segments and carbon or graphite brushes switch the rotor current directly on the shaft. The commutator sits on the rotor, brushes ride on it, and physical contact does the timing. This brings sliding friction, brush wear, copper dust, sparking and broad-spectrum EMI as a package deal.

In electronically or magnetically commutated designs (BLDC, EC motors, PMSMs used with DC supplies), the switching moves into the stator. Power semiconductors in an inverter or driver energise fixed windings based on rotor position, inferred from Hall sensors, resolvers or estimation algorithms. There is no sliding contact in the current path, so there is no brush wear, almost no commutation arcing, and much lower parasitic friction.

Mechanically, the trade is simple: more copper and carbon on the rotor versus more silicon and logic on the stator. Electrically, it is about letting software and gate drivers reshape current instead of relying on discrete copper bars.

Torque quality and control freedom

With a mechanical commutator, the current waveform is baked into geometry. Segment count, brush width and winding scheme give you a particular pattern of current steps as the rotor turns. You can tweak supply voltage and maybe add some external filtering, but the motor decides how sharp the current transitions look. That sets a floor for torque ripple and acoustic noise.

Electronic or magnetic commutation breaks that constraint. For a BLDC or EC motor, the driver can use trapezoidal, sinusoidal or field-oriented control. Same iron, very different behaviour. Trapezoidal current favours simpler drivers and respectable efficiency, at the cost of more torque ripple. Sinusoidal or FOC reduces ripple and acoustic artefacts, allows field-weakening at high speed, and gives you finer control of torque per ampere. None of that is available if the commutator is locked into the rotor metalwork.

There is a catch. Once you move to electronic commutation, you must track rotor position accurately enough, under all operating conditions that matter. That means sensors and wiring, or sensorless estimation with its own failure modes, particularly at very low speed or under stalled conditions. With a mechanical commutator, position tracking is implicit and almost embarrassingly robust.

Reliability, noise and environment

The weak point of a mechanical commutator is obvious: the sliding contact. Brushes wear, commutator bars erode or become fouled, and the dust is both conductive and abrasive. Arcing during commutation creates wideband EMI and obvious sparks, which restricts use in explosive or very noise-sensitive environments. Maintenance intervals and life ratings are dominated by brush and commutator condition, especially under high current or frequent start–stop cycles.

Electronic and magnetic commutation shift the dominant wear item to the bearings. There is no brush dust, almost no internal arcing, and the motor can be sealed tightly. These motors usually run quieter, especially at higher speed, and they naturally fit safety-critical or regulated applications where sparking is not acceptable, such as some electric vehicles, drones in dense RF environments, and equipment around volatile gases.

Reliability is not free though. Semiconductors, position sensors, connectors and firmware create new failure paths: latch-up, ESD, software glitches, sensor misalignment and connector corrosion. The difference is that these failures tend to be abrupt rather than slowly degrading, while mechanical commutation often gives you audible and visible warning before complete failure.

Cost and system-level complexity

If you only look at the motor can, mechanically commutated designs usually win on acquisition cost. No inverter, no gate drivers, no position sensors, simpler PCB, simpler EMC strategy. Two wires and a supply, maybe a simple PWM drive, and the motor spins. For toys, cheap fans, very basic pumps and low-duty mechanisms, that is often enough.

System cost tells a different story once you include maintenance, downtime and regulatory overhead. Electronic or magnetic commutation brings higher motor-plus-driver BOM, but you recover some of that through higher efficiency, reduced cooling needs, less maintenance labour, and the ability to consolidate functions like speed control, diagnostics and protection in firmware instead of separate hardware. Over a multi-year life, particularly in continuous-duty equipment, the total cost often favours the electronically commutated option.

There is also an integration angle. If you already have a reasonably capable microcontroller and power stage on board, hanging a few half-bridges and Hall sensors to run a BLDC can be cheap. If your product is entirely analogue and cost-squeezed, that same move may feel excessive.

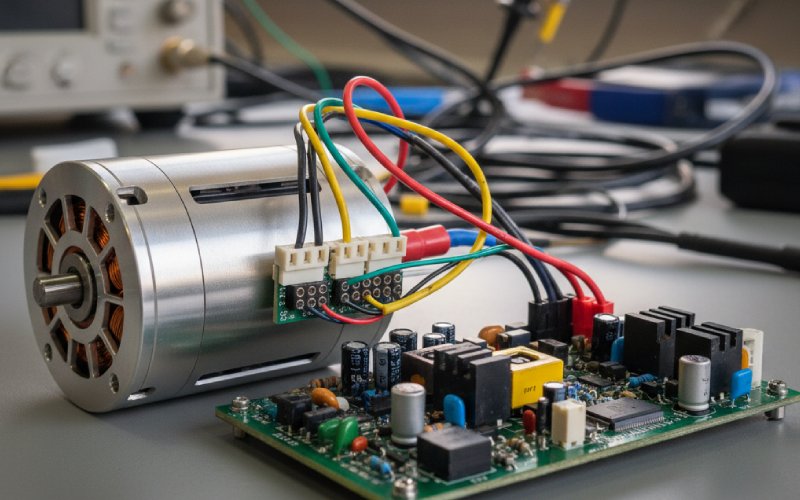

Magnetic and electronic commutation in practice

In many datasheets, “electronically commutated” and “magnetically commutated” motors are essentially brushless DC motors with permanent magnets in the rotor and electronic switching in the stator. The current path does not rotate; the magnetic field pattern does, synthesised by switching the stator phases in sync with rotor position.

The timing can come from discrete Hall sensors, integrated encoder feedback, or sensorless methods that monitor back-EMF, saliency or other signatures. The controller code decides when to switch phases, by how much, and how aggressively to regulate current. That means torque limits, soft-start profiles, speed ramps and protection functions all become adjustable.

From a mechanical point of view, electronic/magnetic commutation also reshapes inertia distribution. With no rotor commutator, it is easier to push copper and magnets into configurations that reduce rotor inertia or move mass outward for outrunners. That matters for dynamic response, especially for applications like gimbals, drones and precision actuators.

Where mechanical commutators still make sense

Despite the clear trend, mechanically commutated DC motors are not going away soon. There are situations where the simplicity is valuable enough to offset the drawbacks.

One example is ultra-low-end motion where cost dominates everything else. Think disposable devices, very low duty appliances and mechanisms that run intermittently at modest currents. The cost of adding an inverter and control logic cannot be justified, and replacing the entire motor after some years is acceptable.

Another case is environments where advanced electronics would be at least as vulnerable as brushes: severe radiation, extreme temperature cycles, or very harsh electrical noise. A simple brushed motor driven by a sturdy relay sometimes survives where microcontrollers and gate drivers struggle, especially when there is no budget for hardened silicon.

Also, in fault-tolerant systems, the behaviour of a brushed DC motor under degraded conditions can be easier to predict. If a brush chip breaks or resistance rises, you get reduced torque or intermittent operation but often still some motion. An electronic commutation stage, when it fails, may stop completely or behave in less graceful ways unless carefully designed.

Quick comparison table

The table below summarises the practical differences in a form you can scan when choosing between mechanical and electronic/magnetic commutation. It is intentionally simplified; real projects will sit somewhere between the extremes.

| Dimension | Mechanical commutator (brushed DC) | Electronic / magnetic commutation (BLDC / EC) |

|---|---|---|

| Commutation element | Rotor-mounted copper segments and brushes | Stator-mounted windings switched by semiconductors |

| Wear and maintenance | Brush and commutator wear, periodic servicing, dust generation | Bearings only in normal use, long service intervals |

| Efficiency band | Lower, with losses in brush contact and commutator friction | Higher, with reduced friction and optimised current waveforms |

| Torque ripple and noise | Set mostly by commutator geometry; limited tuning | Strongly adjustable via control strategy and current shaping |

| EMI and sparking | Arcing at brushes, broad EMI, not ideal for explosive atmospheres | Minimal internal sparking, easier to meet strict EMC and safety rules |

| Speed range | Good at low to moderate speed; practical limits from commutator stresses | Very wide; high speed limited mainly by rotor mechanics and bearings |

| Control features | Basic voltage or PWM control; limited feedback options | Rich control: speed, torque, position, diagnostics and protections in firmware |

| Upfront system cost | Low motor and drive electronics cost | Higher motor plus controller cost, often integrated in modules |

| Total cost over life | Attractive for short-life or low-duty products | Often lower over multi-year continuous duty due to efficiency and reduced maintenance |

| Typical use cases | Toys, small pumps, basic fans, simple actuators | Drones, EVs, HVAC, robotics, precision drives, industrial automation |

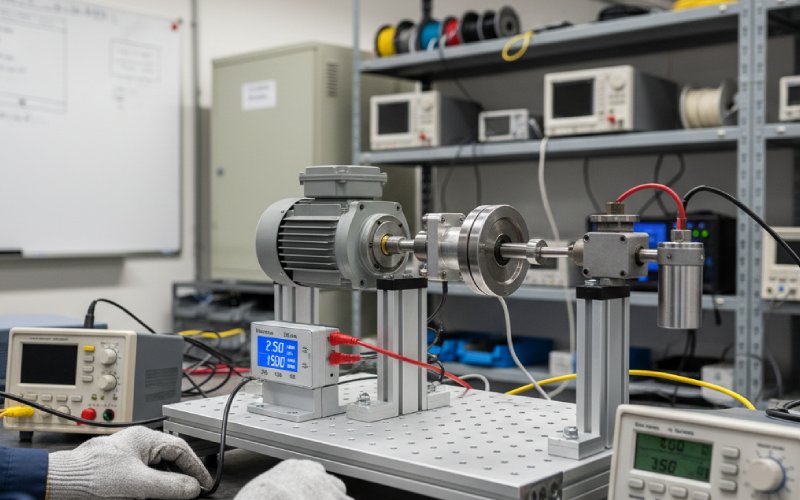

Subtleties that show up late in projects

Two motors that look equivalent on a drawing can behave very differently in the field because of their commutation method. Several effects tend to surprise teams if they were not considered up front.

First, current ripple and supply interaction. A mechanically commutated motor presents abrupt current steps right at the terminals. The commutator geometry sets the pattern, but your wiring inductance and source impedance decide how that plays with the rest of the system. Filters can help, yet there is only so much you can do without changing the motor. With electronic commutation, the same switching happens in the inverter, and you get more freedom to control how current is drawn from the supply. That can simplify compliance with EMC and conducted noise standards.

Second, starting and stall behaviour. Brushed DC motors naturally produce high starting torque with simple drive circuitry, which is useful for loads with static friction or stick–slip issues. Brushless designs can match or exceed that, but only if the controller has a starting strategy that handles unknown rotor position and high load. Otherwise you see twitching, mis-starts or long spin-up times.

Third, diagnostics. Mechanical commutation degrades in visible ways: increased sparking, audible noise, rising current draw. Technicians can often diagnose issues with simple tools. Electronic commutation hides more of its behaviour inside silicon and code, but compensates with self-test, telemetry and logged fault codes if your firmware supports them. That trade changes how you structure service procedures and field support.

How to decide in practice

If you strip away branding and marketing language, the choice usually comes down to a small set of questions.

How long must the product run before any human touches it. If the answer is “years of continuous use” or “maintenance is expensive,” electronic or magnetic commutation tends to win quickly.

How hard is the environment on moving contacts versus electronics. Dust, moisture and explosive atmospheres push you towards brushless designs. Intense radiation or extremes where only very simple electronics survive might still favour a brushed motor with rugged switching.

How much precision you need over speed and torque. If rough speed control via voltage or simple PWM is sufficient, a brushed motor can be fine. If you need tight speed regulation, torque limiting, soft starts, integrated safety and remote monitoring, running those features without an electronically commutated drive becomes awkward.

Finally, how many units you will ship. For very small runs with strict cost caps, the design and software effort for electronic commutation may not pay back. Once volumes grow, the ability to tune control behaviour in firmware and reuse platforms across products usually shifts the economics toward brushless solutions.

Closing remarks

Mechanical commutators gave DC motors their early reach: simple wiring, direct control, no complex electronics. Electronic and magnetic commutation moved the switching problem into silicon and code, and in doing so, quietly changed what designers can ask of a motor in terms of life, control and integration with the rest of the system.

If you think in terms of torque, losses, maintenance and regulatory constraints rather than motor marketing labels, the decision becomes clearer. Brushes are a reasonable answer when you accept wear and noise to keep the system very simple. Electronic or magnetic commutation is the answer when you want the motor to be just another controlled, observable node in a larger system rather than a separate piece of rotating hardware you have to babysit.