How to Make a Commutator (That Actually Works in a Real Motor)

If you care whether the motor survives beyond a lab demo, making a commutator is mostly about controlling geometry, copper, mica and process variation well enough that the brushes behave the way your equations already assume they will. Everything else is decoration.

Table of Contents

What most guides cover — and what they skip

If you search around, you mostly find two kinds of material.

The first kind shows a school-level motor where the “commutator” is foil on a pencil, or a couple of aluminium half-rings taped to foam. It spins, briefly, and teaches the idea. It says little about runout, bar pitch, or brush grade interaction.

The second kind is industrial: notes on segment pitch, mica grades, diameter ratios, undercutting, and maintenance. These are useful, but written as checklists and formulas, not as a story of how you actually get from drawing to reliable production.

This article fills the gap between those two: you already know the theory and the documentation; now you want the judgment calls that sit in the grey space between “designed” and “actually runs”.

Start with the machine, not the copper

It is tempting to open CAD and sketch a commutator around whatever shaft and hub size you inherited. A better order is quieter.

Think about the brush system first: material, number of arms, spring pressure, and allowable current density. The commutator is just the surface that makes those brushes honest.

Design texts will tell you that commutator diameter usually lands around sixty to eighty percent of the armature diameter, with peripheral speed at the working speed kept below roughly fifteen metres per second. Segment pitch is kept above a few millimetres so you have a usable bar width plus mica between bars.

You already know the formulas; the useful move is to start from your worst operating point and ask: at that speed, at that current, with that brush, what is the smallest diameter and segment pitch that still gives a forgiving footprint and acceptable heating margin. That answer, not the prettiest drawing, gives you your first pass geometry.

Geometry that quietly decides if the brushes live or die

A commutator that “looks about right” can still be hostile.

Segment count ties directly to armature coil count and to ripple. You usually do not have full freedom there, but you often have freedom in diameter and axial length. A slightly larger diameter with slightly fewer segments can relax segment pitch constraints, but now the surface speed rises and the brush film behaves differently. A very short axial length keeps the machine compact but pushes you toward higher current density per brush track.

Viewed from the end, each bar is a wedge, thicker at the outside radius, separated by insulation. That wedge shape is not just tradition; it gives you more copper where the brush actually wipes while leaving room for mica at the root.

Skew and staggering matter as well. Small mechanical tricks like staggering brush arms across segments, or choosing a slight skew in the bar stack when manufacturing, can soften commutation for tricky loads. These rarely make it into short documentation; they show up when someone has burned a few sets of brushes and is tired of it.

Materials: copper, mica, plastics, and the real trade-offs

Most serious commutators still use high-conductivity, hard-drawn copper bars separated by mica. Mica appears twice: thin “segment mica” between bars, and separate molded rings or sleeves that insulate the stack from the hub.

In newer semi-plastic designs, you often see a plastic shell that carries the bars, mica sheets between segments, and a metal bushing for the shaft. These architectures respond to higher speed, smaller frame, or more aggressive cost targets.

The engineer’s job is not to repeat “use mica and copper” but to ask: what grade of copper fits our duty and manufacturing flow; what mica thickness keeps the segment pitch within spec and still allows a clean undercut; what shell material can take the press-fit, curing, and operating temperature without creeping.

Even brush grade feeds back into this. A more abrasive brush can tolerate a slightly softer copper and help maintain surface condition, but will eat axial length over time. A soft brush on hard copper might give low wear but be unforgiving of runout.

Key commutator decisions at a glance

Here is a compact way to keep the main knobs in view while you design or review a build.

| Decision area | Typical range or pattern | What it really buys you | Where it hurts you |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diameter versus armature diameter | About 0.6–0.8 of armature diameter with peripheral speed held below roughly 15 m/s at rated speed | Gives a reasonable footprint for brushes and manageable surface speed for film formation and heating | Too small and brush footprint shrinks and heating spikes; too large and surface speed and mechanical stress rise, especially at overspeed |

| Segment pitch and bar width | Segment pitch at least about 4 mm in many industrial designs; bar width chosen to match brush width and mica thickness | Enough copper under the brush to spread current and tolerate slight misalignment; enough mica to stay mechanically robust | Tiny pitch raises insulation difficulty and undercutting risk; excessive pitch limits segment count or forces an oversized diameter |

| Mica grade and thickness | Segment mica thin between bars, molded mica rings for ground insulation; thickness tuned to forming and undercutting process | Stable insulation at operating temperature and pressure; clean undercut gives a clear path for brushes and helps avoid edge chipping | Too thick and you fight bar clamping and undercutting; too thin and you risk copper-to-copper leakage or mica breakdown |

| Shell / hub design | Steel hub with pressed stack, or plastic shell for semi-plastic designs | Defines mechanical stiffness and how segments are located under load; plastic shells help with weight and integration | Poor shell choice leads to growth, cracking, or bar movement during cure or operation; repair becomes difficult |

| Undercut depth and finish | Mica undercut below bar surface by a fraction of a millimetre with clean walls and a slight bevel on bar edges | Ensures brushes ride entirely on copper and wear evenly, reduces arcing and stray mica slivers | Too shallow and brushes ride on mica; too deep and you weaken support for the bar edges and invite chipping or carbon packing |

You can treat this table almost like a mental pre-flight check: if any column feels extreme for your design, expect to pay for it later in brush wear or commutator maintenance.

Industrial manufacturing flow, without the brochure tone

At production scale, making a commutator is not a single act; it is a chain of small operations that all have ways to go slightly wrong.

Copper strip is punched or machined into L- or V-shaped segments that will form the bars and risers. Insulation sheets are punched to match, usually with deliberate extra length to project slightly on the riser side so the insulation is not flush and vulnerable.

Those segments and mica pieces are stacked into a steel or plastic shell, often in a tool that enforces bar spacing and roundness. The stack is pressed, sometimes molded with resin, and cured so that everything becomes one tight unit around the hub.

After curing, the outer surface is turned to the target diameter on a lathe or dedicated machine. Now you have something that looks like a commutator, but it is not finished. The mica between bars is undercut to a controlled depth so that brushes run only on copper. Documents on maintenance describe several methods for this undercut: saw-type undercutters, flexible shaft tools, and hand methods. All share the same goal of removing mica between bars without chipping the copper and leaving clean, straight slots.

The bar edges are then bevelled slightly, the surface is lightly dressed with fine abrasive, and runout is checked. Practical machinists will remind you to clean out every trace of copper dust between bars after turning and undercutting; leaving conductive dust bridges defeats the whole point.

Throughout this, the subtle skill lies in fixtures, heat treatment, and handling. A theoretically perfect stack that warps during cure or clamps out of round can never be corrected fully; you will chase runout forever.

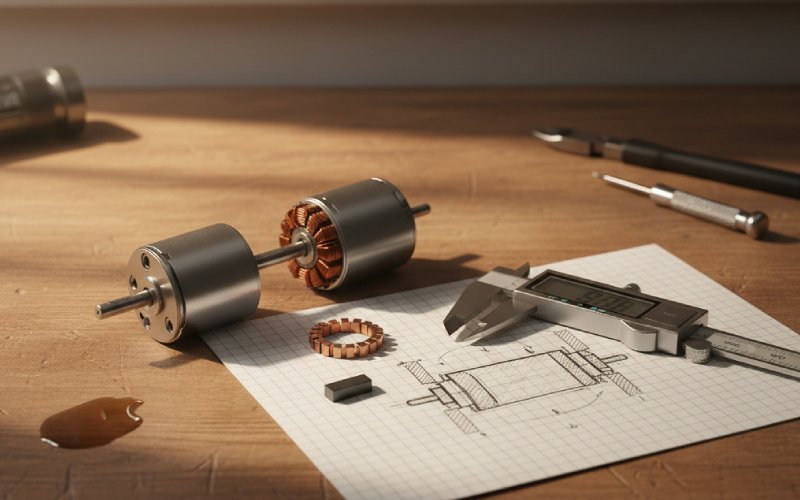

Building a one-off bench commutator (when you are not a factory)

If you are prototyping a small DC motor on the bench, you obviously are not going to set up a full commutator line. You still can borrow its logic.

Simple teaching motors often make the commutator by gluing narrow copper plates around a wooden dowel, each plate bent to follow part of the circumference. As long as the plates never touch electrically and the surface is reasonably round, this works for light duty.

Another common approach uses a short piece of copper pipe or connector, cut, then split into two or more arc pieces that are slid back over an insulated core to form multiple segments. Some school-level builds use aluminium foil half-rings taped to foam or to a pencil as a quick substitute.

You can take these ideas and push them a bit closer to professional practice without making life too hard. Use a good, stable core material instead of random wood. Ensure the segments seat against a consistent diameter so runout is not terrible. Machine or sand the assembled segments in a lathe or a jig until the surface is concentric with the shaft. Leave narrow insulating gaps that you can later clean with a fine saw blade or a thin file to mimic undercutting.

It will not be pretty the first time. That is fine. What matters is that you treat concentricity, segment isolation, and surface condition as non-negotiable, even in a “quick” prototype.

Process control: where most commutators actually fail

Once motors are in service, maintenance guides talk relentlessly about the same themes: undercut condition, surface burnishing, and brush contact pattern.

Undercutting is not a one-time event; mica is harder than copper and does not wear as quickly. If you never re-establish the recess, the brushes eventually ride on mica, arc, and wear badly. Industrial guidance recommends periodic inspection and, when needed, re-undercutting with controlled tools and then re-chamfering the bar edges.

Surface condition also tells a story. A smooth, graphite-tinted surface with even brush tracks suggests your geometry, materials, and process all lined up. Banding, heavy streaks, or copper pulling at the trailing edge of bars suggest poor film, runout, or wrong brush pressure. The point here is simple: if you design and make the commutator well but never look at it under working conditions, you are throwing away most of the effort.

From a manufacturing viewpoint, control the steps that silently introduce variation. Track runout at each critical stage: after pressing, after rough turning, after finish machining, after assembly to the armature. Watch cure temperature and time so the shell and bars do not shift relative to each other. Keep an eye on undercut depth; do not let operators “eyeball” it into a different value every shift.

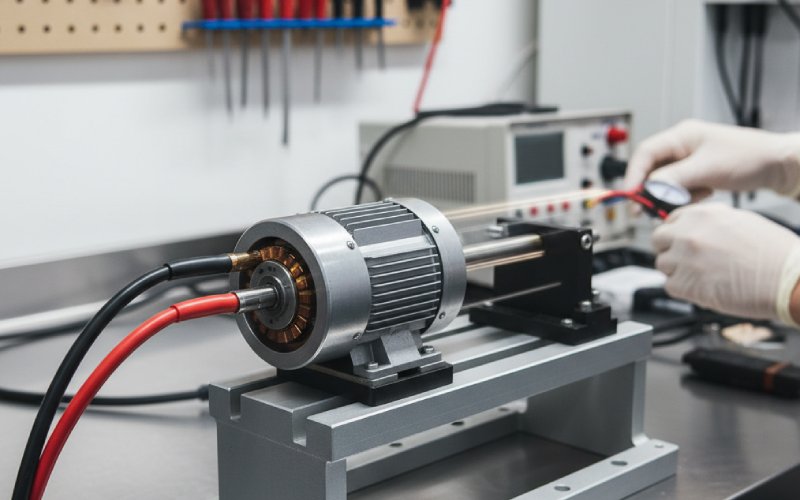

A pragmatic testing loop

When you finally put the motor on test, think less about hero data and more about short feedback loops into your commutator process.

Run at light load first and inspect the contact pattern. If brush marks land across the full intended width of the bar, and there are no obvious high bars, your concentricity is probably good enough. If you see partial contacts, streaks, or bars that take significantly more contact than neighbours, take that back to your geometry and machining.

Follow with thermal checks at the worst realistic duty point. Excessive temperature rise at the commutator compared with the rest of the armature can hint at contact resistance, wrong brush grade, or inadequate copper section in the bars.

Over a longer run, inspect mica condition, undercut sharpness, and any signs of copper drag at bar edges. Maintenance documents show how even a thin mica sliver left behind can cause trouble; this is not theory, it is daily shop practice.

Each of these observations is a lever back into design and manufacture. Adjust brush grade or pressure if the surface film never stabilises. Revisit segment pitch or diameter if arcing persists at specific speeds. Tighten your undercutting and cleaning process if carbon packs into slots or mica protrudes.

The quiet summary

Making a commutator is not about a single clever trick. You choose geometry that respects the brushes you plan to use. You pick copper, mica, and shell materials that stay stable under your mechanical and thermal reality. You build a manufacturing flow that protects roundness, bar spacing, and insulation. Then you watch what actually happens in the motor and feed that information back.

Do that cycle a few times and your commutators stop being classroom hardware and start behaving like parts that belong in serious machines.