How to Clean an Electric Motor Commutator (Without Wrecking It)

If your electric motor has started sparking, losing torque, or sounding rough, there’s a good chance the commutator needs attention. Cleaning it sounds simple… right up until you realize you’re about to scrub the part that carries all the current in and out of the rotor.

Done badly, commutator “cleaning” can do more harm than the original dirt: accelerated brush wear, arcing, or even a ruined armature. Done well, it can bring a tired motor back to life and add years to its service.

- In this guide, you’ll learn:

- What a commutator actually does (in human language, not textbook jargon)

- How to tell if it really needs cleaning (or something more serious)

- Safe, step-by-step cleaning methods — from quick touch-ups to deeper work

- What tools and materials to use (and which ones quietly destroy motors)

- A simple maintenance routine so you don’t end up here again in six months

Table of Contents

1. First, what exactly are you cleaning?

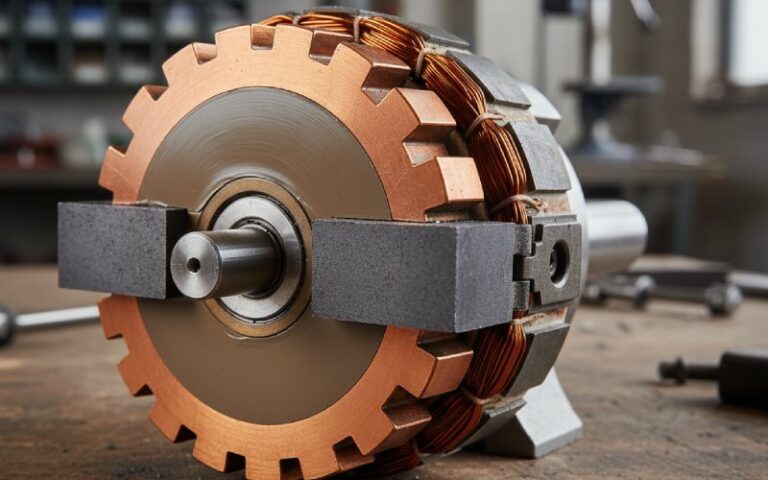

On a brushed DC or universal motor, the commutator is the copper cylinder with segmented bars that the carbon brushes ride on. Its job is to act like a rotary switch, constantly flipping current direction so the motor keeps turning.

Over time, a few things build up on that copper surface:

- Carbon dust from the brushes

- Oil mist and grease vapor from bearings or the environment

- Tiny copper particles from normal wear

- Occasionally, burnt spots from arcing

A thin, even dark film of carbon on the commutator is actually normal and even beneficial — it helps the brushes slide smoothly. The problem is uneven buildup, ridges, grooves, or contamination that interrupts good contact.

- You’re probably dealing with a dirty or damaged commutator if you notice:

- Excessive sparking at the brushes

- A sizzling, crackling, or “fizzy” sound from the brush area under load

- Uneven wear on brushes (one side chipped, ridged, or burnt)

- Visible grooves, pits, or burnt spots on the copper bars

- Intermittent loss of power, especially under higher load

- A strong burnt smell around the motor when it runs

2. Safety before screwdrivers

Before you touch anything, remind yourself: this is a powered, rotating, electrically live device when running. Even a “small” tool motor can give a serious shock, and industrial motors can be lethal.

Always start by fully isolating the motor:

Unplug portable tools, disconnect battery packs, and lock out/tag out larger motors so they cannot be energized while you’re working. Let the motor fully stop and cool down, especially if it has been running hot.

- Minimum safety checklist:

- Cut power: unplug, open the breaker, and apply lockout/tagout where applicable.

- Discharge: for systems with capacitors (inverters, drives), wait for discharge per manufacturer instructions.

- PPE: wear safety glasses, dust mask/respirator (carbon dust is not a vitamin), and gloves when using solvents.

- Ventilation: work in a well-ventilated area if you’re using contact cleaner or isopropyl alcohol.

- No jewelry: remove metal rings and watches that can short live terminals if someone accidentally energizes the system.

- Respect your limits: on large or high-voltage motors, involve a qualified motor shop.

3. Tools and materials: what to use (and what to avoid)

There’s a lot of conflicting advice online about “just use sandpaper” or “only a pencil eraser.” Let’s decode it using what motor manufacturers and repair pros actually recommend.

For light to moderate cleaning, common best practices include:

- A soft brush and vacuum to remove loose carbon dust and dry debris, instead of blowing it deeper into the windings.

- A lint-free cloth, dry or very slightly dampened with a suitable solvent like isopropyl alcohol or residue-free contact cleaner (if the motor’s documentation allows solvents).

- For heavier film, a commutator stone or fine, non-conductive abrasive used sparingly to refresh the surface.

At the same time, some technical bulletins explicitly warn against solvents on commutators and brush gear because they can carry conductive dirt deeper into insulation or leave residues.

So the “grown-up” rule is:

Follow the motor manufacturer’s maintenance recommendations first. If there’s any conflict, the manual wins.

- Common tools & supplies (pick based on how bad yours is):

- Soft brush + vacuum cleaner (ideally with a brush attachment)

- Lint-free cloths or shop wipes

- Isopropyl alcohol (IPA) or dedicated contact cleaner (non-residue)

- Plastic or wooden picks for cleaning the mica slots

- Commutator stone or very fine, non-emery abrasive (e.g. garnet paper, 600–1000 grit)

- Small screwdriver set and pullers (for disassembly if needed)

- New brushes (if your old ones are worn short or cracked)

4. Quick reference: how bad is it?

Use this table as a mental “triage” chart before you decide how deep you need to go.

| Condition | What you see | Recommended cleaning | Likely repair level |

| Light dust / normal film | Even dark ring, minimal sparking | Vacuum + soft brush, quick wipe with cloth | Basic maintenance |

| Oily or greasy contamination | Shiny patches, dust stuck in sludge | Careful solvent wipe (if allowed) + vacuum | Basic to intermediate |

| Heavy carbon build-up / streaks | Dark streaks, uneven film, more sparking | Commutator stone or fine abrasive, then thorough clean | Intermediate; check brushes closely |

| Grooves or stepping between bars | Visible ridges, brushes “tick” over surface | Light stone only if shallow; otherwise machine in shop | Professional resurfacing recommended |

| Burnt, pitted, or blue-black copper | Craters, melted spots, burnt smell, severe sparking | No DIY sanding – send armature to a motor repair shop | Professional repair / possible replacement |

This table alone will already put you ahead of a lot of generic “wipe it with sandpaper” advice.

- Situations where you should strongly consider a motor shop:

- The motor is critical to production or safety (e.g. hoists, cranes, elevators).

- Voltage is high or you’re not confident working around power systems.

- The commutator is badly grooved, oval, or has deep burns/pits.

- There is evidence of insulation breakdown or serious overheating.

- The motor is under warranty and you’re not following the official procedure.

5. Step-by-step: basic commutator cleaning (no full teardown)

This is the “gentle” method for motors that only have dust, light film, or mild contamination — think power tools, small DC drives, sewing machines, or hobby motors that still run but show extra sparking or noise.

The goal here is to clean without grinding away copper. You’re removing contaminants, not trying to make the commutator look like a mirror-finished showpiece.

- Basic cleaning steps:

- Isolate power and remove covers

- Unplug / disconnect and remove the outer shroud or end bell to expose the brushes and commutator. Take photos as you go so you can reassemble everything correctly.

- Inspect brushes and commutator

- Check that brushes still have adequate length and move freely in their holders. Look at the commutator for evenness: a smooth, even band is good; streaks or spots indicate where to focus.

- Vacuum loose dust

- Use a soft brush and vacuum to remove loose carbon dust and debris. Avoid blasting with high-pressure air; it can drive conductive dust deeper into windings and insulation.

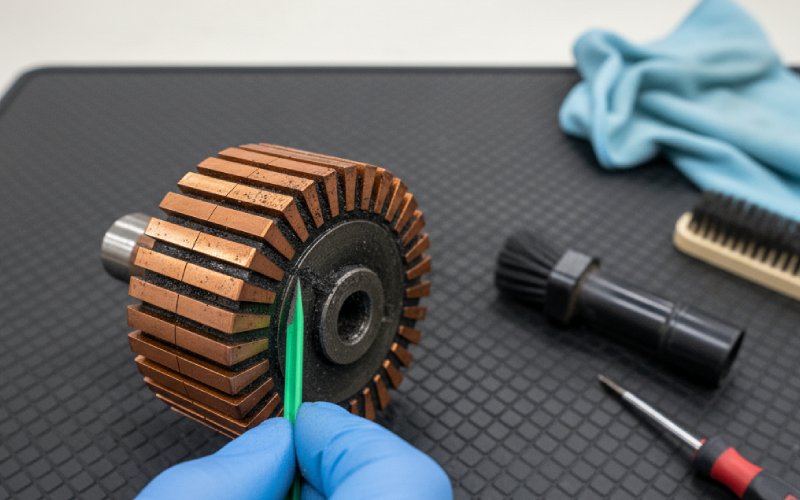

- Wipe the commutator surface

- Rotate the armature by hand while gently wiping the copper with a lint-free cloth. If needed, very lightly dampen the cloth with IPA or non-residue contact cleaner, making sure it doesn’t puddle or drip into the windings.

- Clean the brush faces (if allowed)

- Some techs lightly rub the brush face on clean paper or a commutator stone to remove glazing. Do not radically reshape the brush; you’re just refreshing the surface.

- Clean between the bars (lightly)

- If there’s visible debris or carbon packed between commutator segments, gently clear it with a plastic or wooden pick, then vacuum again. This helps prevent tracking and cross-shorts between bars.

- Reassemble, seat brushes, and test

- Reinstall covers, make sure brushes sit properly and springs apply sensible pressure. Run at no-load first, listening for abnormal sparking or noise.

- Isolate power and remove covers

6. Intermediate cleaning: using a commutator stone or fine abrasive

Sometimes wiping isn’t enough. If the commutator has light ridges, mild streaking, or uneven film, you may need a bit of controlled abrasion. Many motor maintenance guides recommend commutator stones or fine, non-conductive abrasives for this.

The key phrase is controlled. You’re aiming to restore a smooth, concentric surface — not to “polish” the life out of the commutator.

- Guidelines for abrasive cleaning:

- Prefer a commutator stone or garnet paper over generic sandpaper:

- Never use emery cloth with aluminum oxide; conductive particles can embed in the surface and cause arcing and further damage.

- Use a very fine grit (e.g. 600–1000) if you must use paper, and only enough pressure to kiss the surface.

- Support the abrasive on a rigid backing so it stays flat against the commutator.

- Rotate the armature by hand while holding the stone/paper gently, keeping it steady and not rocking.

- After abrasion, thoroughly vacuum the area and wipe the commutator to remove all dust and abrasive residue.

- Recheck the mica undercut and brush contact pattern when you’re done.

- Prefer a commutator stone or garnet paper over generic sandpaper:

7. Cleaning the mica undercut (between commutator bars)

Between each copper bar is an insulating material (often mica). In many DC motors, this mica is machined slightly lower than the copper surface so the brushes ride only on copper. If dirt, copper, or carbon builds up in those slots, or if the mica is flush with the copper, the brushes can “ride up,” resulting in arcing and poor commutation.

As a DIYer or technician, you generally do not want to deepen the undercut aggressively unless you know the original spec. But you can safely:

- Remove packed dust and debris.

- Ensure there are no conductive bridges between bars.

- Light mica slot cleaning steps:

- Use a plastic, fiber, or wooden tool (never a steel screwdriver) sized to fit the gap.

- Gently scrape out compacted carbon or debris between bars, following the slot, not cutting deeper into insulation.

- Rotate the armature and repeat for every segment, keeping pressure light and controlled.

- Vacuum the entire commutator area thoroughly afterward.

- Inspect visually with good lighting; you should see clean, distinct gaps with no shiny copper smear bridging between segments.

8. What you should not do (ever, if you can help it)

Some “shop tricks” are popular because they’re fast, not because they’re good for the motor’s long-term health. A lot of damage comes from enthusiastic over-cleaning.

In particular, driving solvents or abrasive dust into insulation and windings can shorten the motor’s life even if it looks great right after you’re done.

- Biggest commutator-cleaning mistakes:

- Using emery cloth or aluminum-oxide abrasives on the commutator → Conductive particles can embed in copper and cause chronic arcing.

- Soaking or flooding the motor with solvent → Liquid can wash conductive dust deep into crevices and insulation, causing tracking and eventual failure.

- Grinding away large amounts of copper just to make it “look new” → You shorten commutator life and may change its geometry; serious reshaping belongs in a machine shop.

- Aggressively cutting mica deeper without specs → Over-undercutting can weaken the structure and alter brush dynamics.

- Ignoring brush condition while obsessing over the commutator → Worn, wrong-grade, or stuck brushes can cause problems that no amount of cleaning will fix.

- Trying to “clean” a motor that’s clearly burnt → Heavy blue/black discoloration, melted solder, or strong burnt smell is a sign to send it to a professional, not just scrub it.

9. Aftercare: seating brushes and running-in

Once you’ve cleaned the commutator and ensured brushes move freely, you want the contact between brushes and copper to be as even as possible. A brush that only touches on a small area will run hot and wear fast.

Some setups use seating stones or special sandpaper to shape new brushes to the commutator radius, but even without that, a gentle run-in helps:

Run the motor at light load first, observing sparking and temperature. A small, even ring of contact should gradually appear on the brush face, and sparking should reduce as the contact improves.

- Post-cleaning checklist:

- Brushes move freely and are above the minimum recommended length.

- Brush springs apply firm but not excessive pressure.

- Commutator surface is smooth, with no loose debris or embedded grit.

- Slots between bars are clean and not bridged by copper smear or compacted carbon.

- Motor runs quietly at no-load, with only minimal, uniform brush sparking.

- After a short loaded test run, the commutator is warm but not excessively hot or discolored.

10. Simple maintenance schedule to keep it clean

Like changing engine oil, light, regular maintenance beats heroic rescue missions. For many industrial DC motors, guides suggest inspection intervals in the hundreds of operating hours; for hobby tools, you might think in months of usage instead.

If you note how your motor behaves when it’s healthy, you’ll be much faster at spotting when it starts to drift.

- Practical routine (adjust for your use case):

- Every few weeks / 20–50 hours (light use):

- Quick visual check of brushes and commutator through access ports if available.

- Listen for new noises or changes in sparking.

- Every 3–6 months / 200–500 hours:

- Isolate power, remove covers, vacuum dust, and check brush freedom and length.

- Wipe commutator if there’s any visible contamination.

- Every 500–1000 hours or at major service intervals:

- Full inspection of brush grade, spring pressure, and commutator condition.

- Light stone/abrasive clean only if necessary, plus mica slot inspection.

- Replace brushes nearing their minimum length and re-seat.

- Every few weeks / 20–50 hours (light use):

11. Quick FAQs (so you don’t have to Google them later)

Q: Can I always use isopropyl alcohol or contact cleaner?

Not always. Some technical documents explicitly advise against solvents on commutators and brush gear, while others recommend gentle solvent wiping. Treat the motor’s own manual as the deciding vote. When in doubt, keep things dry and minimal.

Q: Is sandpaper automatically bad?

The real villain is emery or aluminum-oxide abrasives that leave conductive particles. Very fine garnet or similar non-conductive paper used sparingly can be acceptable in many repair practices, but commutator stones are safer and purpose-made.

Q: Do brushless motors need commutator cleaning?

No. Brushless DC (BLDC) motors use electronic commutation and don’t have a mechanical commutator. If you don’t see brushes and copper bars, you’re in a different world (still needs maintenance, but not this kind).

Q: How do I know it’s too far gone for DIY?

If the commutator is badly grooved, oval, severely pitted, or the motor shows signs of insulation failure or heavy overheating, a motor rewinding/repair shop is the right move. No amount of sanding will fix burnt copper or damaged insulation safely.

12. Bringing it all together

Cleaning an electric motor commutator isn’t magic — it’s a careful balance between doing enough to restore clean, even contact and not doing so much that you chew away copper or damage insulation.