How Does a Commutator Work?

If you’ve ever looked at a DC motor or generator diagram and thought, “Okay, I see this copper cylinder called a commutator… but what is it really doing?” — you’re in the right place.

At its core, a commutator is a clever mechanical switch that keeps electrical and magnetic forces lined up so a motor keeps spinning in one direction or a generator delivers usable DC power. It’s the unsung little device that turns back-and-forth physics into one-way useful motion or current.

- In one sentence: A commutator is a rotating copper “switch” on the rotor that reverses the direction of current in each coil at just the right time so that torque (in motors) or output current (in generators) stays in a single, useful direction.

Table of Contents

1. What is a commutator, really?

Imagine you’re pushing someone on a swing. If you kept randomly switching directions, the swing would just jerk around. But if you time your pushes so you’re always pushing forward at the right moment, the swing goes higher and higher.

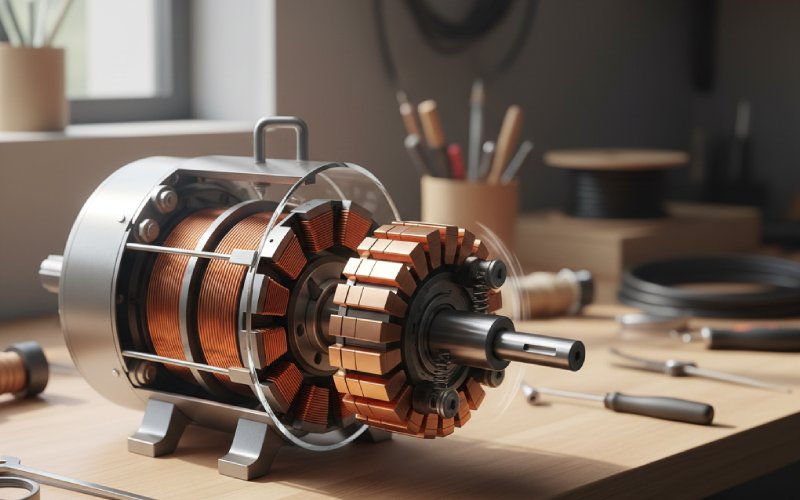

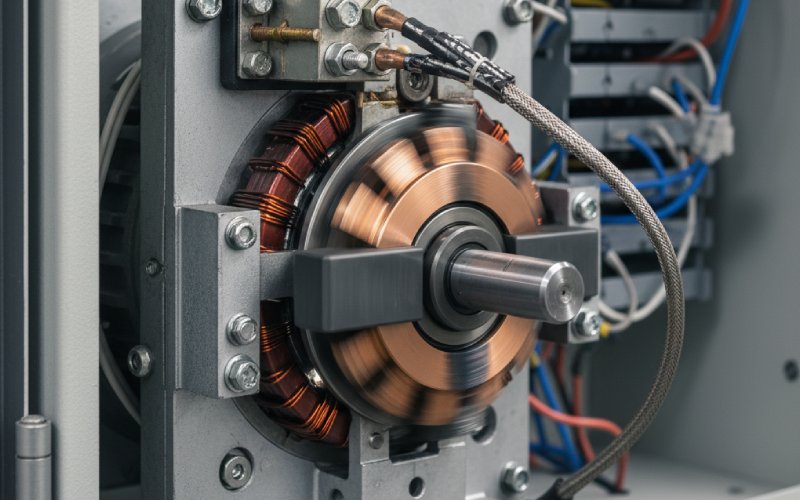

The commutator is the timing genius inside a DC machine. It sits on the rotating shaft (armature) and is made from many copper segments insulated from each other. As the shaft spins, stationary carbon or copper brushes rest on the commutator and naturally connect to different segments over time. That simple sliding contact is what silently “rewires” the motor or generator every fraction of a turn.

- You can think of the commutator as:

- A rotary electrical switch mounted on the rotor.

- Made of multiple copper segments, separated by insulating material (often mica).

- Connected internally to the armature windings (each coil ends on a pair of segments).

- Touched by spring-loaded brushes that carry current between the spinning armature and the stationary world.

- A rotary electrical switch mounted on the rotor.

2. Why do we even need a commutator in a DC motor?

When current flows through a conductor placed in a magnetic field, it experiences a force (hello, Fleming’s Left-Hand Rule). Inside a DC motor:

- The armature has coils wound on an iron core.

- Those coils sit in the magnetic field of the stator (permanent magnets or field windings).

- Current flows in opposite directions on opposite sides of the coil, giving forces that create torque.

Here’s the catch: as the rotor turns, the sides of the coil move to the opposite magnetic poles. If the current direction stayed the same relative to the coil, the torque would flip direction every half-turn, and the rotor would just rock back and forth instead of spinning continuously. That’s useless for a motor.

The commutator solves this by reversing the current in each armature coil exactly when it passes through the neutral position, keeping torque always pushing in the same rotational direction.

- In a DC motor, the commutator’s job is to:

- Feed DC power from the external circuit into the rotating armature via the brushes.

- Reverse the current in each coil every half-turn (or at the correct angular interval for multipole machines).

- Keep the electromagnetic torque unidirectional, so the rotor spins smoothly instead of oscillating.

- Act as a mechanical inverter of coil currents, synchronized naturally with rotor position.

- Feed DC power from the external circuit into the rotating armature via the brushes.

3. Step-by-step: a simple 2-pole motor with a commutator

Picture the simplest possible DC motor:

- One rectangular coil.

- A two-segment split-ring commutator.

- Two brushes connected to a DC supply.

- A north and south stator pole.

As the coil turns, the commutator keeps flipping which side of the coil connects to which brush. That’s the magic.

- Oversimplified flow of events in one revolution:

- Start position: One side of the coil is under the north pole, the other under the south pole. Forces act to start rotation.

- Approaching 90°: Torque is maximum; the coil is horizontal, still being pushed in the same rotational direction.

- At 90° (neutral plane): The coil sides momentarily cut no flux; induced EMF is near zero. At this very convenient instant, each brush moves onto the next segment, which effectively reverses the current in the coil.

- Beyond 90°: The coil sides have swapped poles, but because the current reversed, forces still push in the same rotational direction as before.

- Repeat: Every half-turn, the commutator repeats this trick, keeping the motor spinning smoothly.

- Start position: One side of the coil is under the north pole, the other under the south pole. Forces act to start rotation.

4. In a DC generator: commutator as a “mechanical rectifier”

Flip the story: instead of feeding electrical power in and getting rotation out , you push the shaft mechanically and want electrical power out (generator).

- As the armature coils spin in the magnetic field, they generate an alternating EMF in each coil (first positive, then negative as the coil moves through the field).

- Without a commutator, the terminals would deliver AC.

- The commutator reverses the connections of each coil with the external circuit every half-turn, so the external terminals always see current in the same direction — effectively converting internally generated AC into external DC.

You’ll often see it described as a mechanical rectifier — doing the same conceptual job as a diode bridge, but with sliding copper and carbon instead of silicon.

- Key roles of the commutator in a DC generator:

- Collects current from the rotating armature coils through the brushes.

- Flips the coil connections to the external circuit every half-turn.

- Turns the alternating induced voltage in each coil into pulsating DC at the terminals.

- Simplifies the external circuit: no electronics needed in classic designs, just copper and carbon.

- Collects current from the rotating armature coils through the brushes.

5. Motor vs Generator: what changes for the commutator?

The hardware looks almost the same in a DC motor and a DC generator, but the “story direction” is reversed.

| Aspect | In a DC Motor | In a DC Generator |

| Energy flow | Electrical → Mechanical | Mechanical → Electrical |

| What armature coils “want” | They would experience alternating torque if unchecked | They naturally generate alternating EMF |

| Commutator main role | Reverse coil current to keep torque direction constant | Reverse coil-to-load connection to keep load current direction constant |

| How it’s often described | “Keeps the motor spinning in one direction” | “Acts as a mechanical rectifier to get DC from an AC-producing armature” |

| External circuit sees | Approx. constant-direction armature current (torque unidirectional) | Pulsating DC voltage and current |

| If commutator were removed | Motor would simply oscillate or stall | Generator output would be AC instead of DC |

- So conceptually:

- Motor: Commutator works on current inside the coils, making torque steady.

- Generator: Commutator works on connections to the load, making output current steady in direction.

- Same copper segments, different storytelling direction, same underlying reversal trick.

- Motor: Commutator works on current inside the coils, making torque steady.

6. What actually happens during “commutation” (the subtle part)

In real machines, commutation isn’t an instant flick; it’s a short interval while a brush is touching two adjacent segments at once. During that brief time:

- The coil connected between those two segments is momentarily short-circuited through the brush.

- The current in that coil has to reverse direction while the coil is shorted.

- Because coils have inductance, they resist abrupt current change, which can cause sparks and heating if commutation is poor.

Engineers spend a surprising amount of effort getting this tiny slice of the rotation just right.

- To improve commutation, machine designers use:

- Correct brush positioning: Brushes are placed on the magnetic neutral plane, where induced EMF is minimal, so current can reverse with less fighting against induction.

- Interpoles (commutating poles): Small auxiliary poles placed between main poles, connected in series with the armature, producing a local field that helps reverse current in the short-circuited coil.

- Proper brush material: Carbon/graphite brushes have enough resistance and friction properties to soften the switching and limit sparking.

- Shaped or skewed slots/armature: Reduces sudden changes in flux, smoothing out the commutation process.

- Correct brush positioning: Brushes are placed on the magnetic neutral plane, where induced EMF is minimal, so current can reverse with less fighting against induction.

7. The downsides: why commutators aren’t everywhere anymore

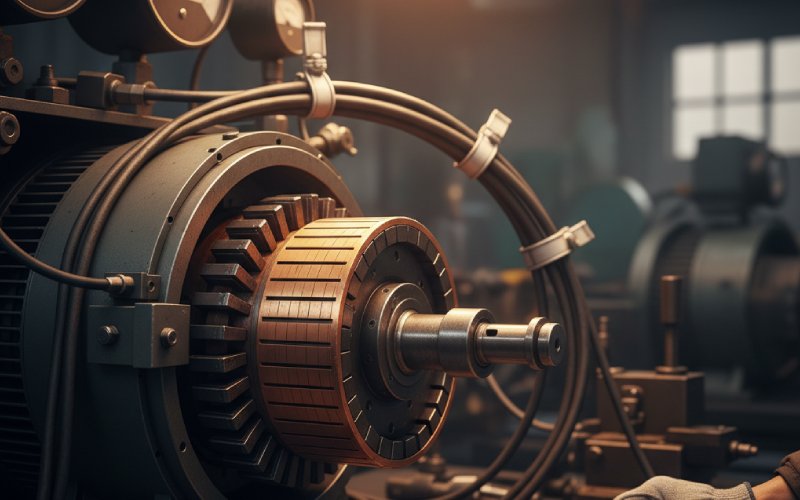

Classic DC machines with commutators powered trains, factories, early electric vehicles, and more. But modern systems increasingly avoid them because they come with some baggage.

Commutators:

- Need sliding contact, which means mechanical wear.

- Have a voltage drop across the brush–commutator contact (called brush drop), which wastes power — nasty for low-voltage, high-current machines.

- Spark if commutation isn’t perfect or if dust/oil builds up.

- Generate electromagnetic noise and can be hazardous in explosive atmospheres due to sparks.

- Are hard to scale efficiently to very large power ratings; big DC machines are generally replaced by AC machines.

- Because of these limitations, you’ll often see:

- AC induction and synchronous motors in big industrial drives instead of giant DC commutator motors.

- Brushless DC (BLDC) motors in fans, drones, EVs, and hard drives — they use electronic switches (transistors) to do what the commutator used to do mechanically.

- Longer lifetimes and less maintenance, because the “commutator” is now solid-state electronics, not copper segments rubbing under springs.

- AC induction and synchronous motors in big industrial drives instead of giant DC commutator motors.

8. In one last breath…

A commutator isn’t just some copper cylinder engineers slap onto a motor because textbooks say so. It’s a beautifully timed rotary switch that:

- In motors, keeps torque pushing in the same direction by reversing coil currents at precisely the right angle.

- In generators, straightens out a naturally alternating armature output into direct current for the outside world.

- Does all this with nothing more than copper, carbon, springs, and geometry.

Once you see it as a synchronized choreography between coils, magnets, and sliding contacts, every DC motor or generator cutaway suddenly makes sense — and that mysterious copper drum stops being mysterious at all.