How a Commutator Converts AC to DC (In a Way That Actually Feels Intuitive)

Imagine you’ve got a tiny loop of wire spinning in a magnetic field. Deep inside a DC generator that’s exactly what’s happening – and what that loop naturally produces is AC, not DC. Yet at the generator terminals, you measure DC. The “magic” in between is a very down-to-earth device: the commutator.

Table of Contents

1. First truth: the generator wants to make AC

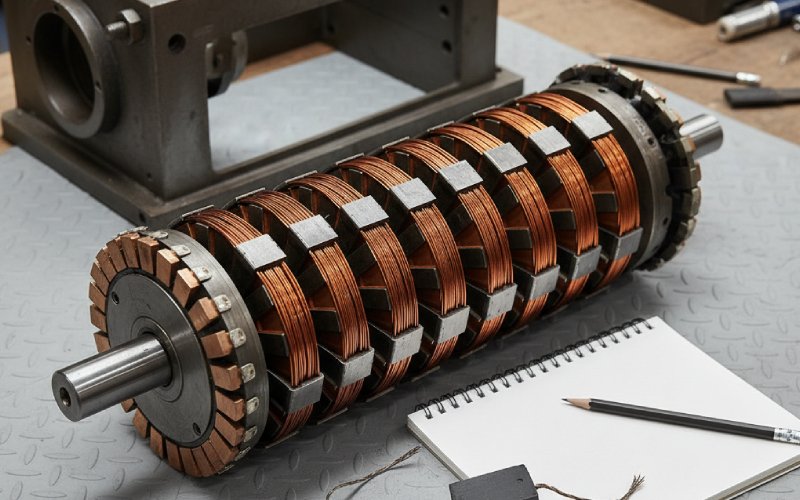

Inside a DC generator, the armature winding (coils on the rotor) cuts magnetic flux as it rotates. By Faraday’s law, any time the flux linkage through a loop changes, an EMF is induced. As the loop goes past north and south poles, the direction of that EMF keeps reversing, giving a sinusoidal (AC) waveform in each conductor.

If you could somehow solder wires directly to the rotating coil and bring them out (forget brushes and commutator), you’d get:

- A voltage that starts at 0, rises to a positive maximum, falls back to 0, then goes negative, and so on.

- In other words: pure AC from that rotating loop.

- What a single rotating loop does (conceptual positions)

As the loop rotates in a uniform magnetic field:- Position 0° – Loop sides move parallel to the magnetic field → flux cutting is zero → induced EMF ≈ 0.

- Position 90° – Loop sides cut flux at right angles → flux cutting is maximum → EMF is maximum and positive.

- Position 180° – Back to parallel → EMF ≈ 0 again.

- Position 270° – Cutting flux in the opposite sense → EMF is maximum but negative.

- Complete one mechanical revolution → one full AC cycle in that loop.

- Position 0° – Loop sides move parallel to the magnetic field → flux cutting is zero → induced EMF ≈ 0.

2. Meet the commutator: a rotary polarity flipper

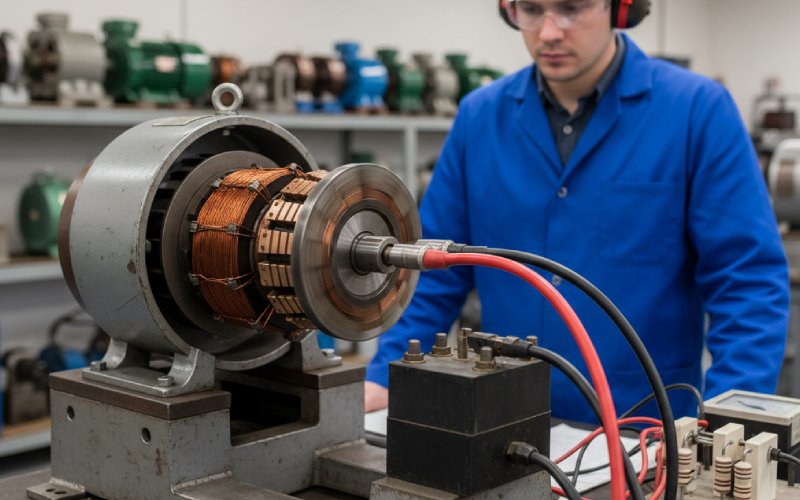

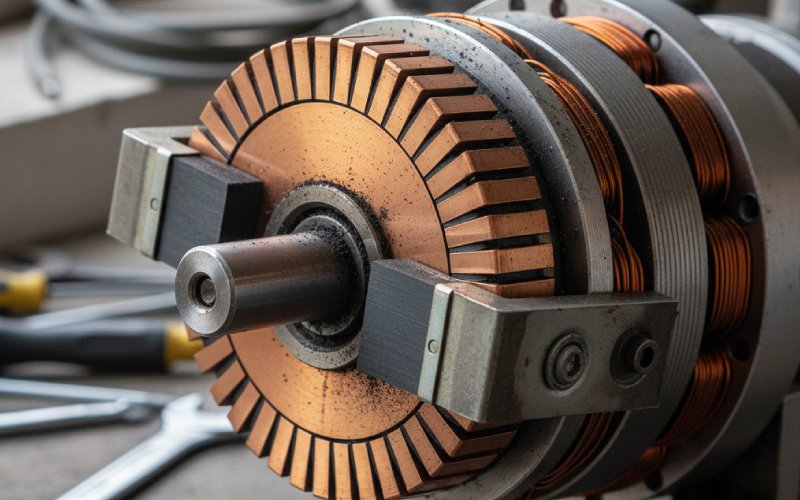

A commutator is basically a rotary electrical switch attached to the same shaft as the armature. It’s made of copper segments insulated from each other (often by mica) and connected to the armature coils. Two stationary carbon brushes press on the rotating segments and lead out to the external circuit.

In simple terms:

- The commutator is like someone physically unplugging and re-plugging coil leads every half-turn,

- precisely timed so that the terminals outside always see the same polarity, even though the coil’s internal EMF keeps reversing.

- The main pieces at a glance

- Commutator segments

Copper blocks arranged around the shaft, each tied to an armature coil end. - Insulation

Thin layers (e.g., mica or resin) between segments and between segments and shaft to prevent short circuits. - Brushes

Usually carbon/graphite blocks that stay still, pressed against the segments with springs. - Armature coils

Ends of each coil are connected to particular segments in a pattern that defines the winding (lap, wave, etc.).

- Commutator segments

3. The core idea: AC inside, DC outside

Here’s the mental reset that makes everything click:

The armature coils generate AC. The commutator’s job is to re-map that AC so the external circuit sees DC.

Think in terms of frames of reference:

- Coil’s view: “My EMF changes direction every half turn.”

- External terminals’ view: “Whatever is connected to the positive brush is always the side of the coil currently generating the positive half-cycle.”

The commutator accomplishes this by swapping which coil end is connected to which brush every half revolution. So whenever the coil’s EMF is about to go negative, its connection to the external terminals is flipped, making that negative half-cycle appear positive at the terminals.

Inside vs outside: what each part “feels”

| Region of rotation (approx.) | EMF in the coil itself | Which segment touches the + brush? | What the external circuit sees |

| 0° → 90° | Rising positive AC | Coil end A (via segment A) | Rising positive voltage at + terminal |

| 90° → 180° | Falling positive | Still coil end A | Falling positive voltage |

| 180° → 270° | Now negative AC | Coil end B (via segment B) | Still positive at + terminal (because leads are swapped) |

| 270° → 360° | Negative → 0 | Still coil end B | Positive → 0 at + terminal |

So the coil EMF is AC, but the commutator flips connections exactly when polarity reverses, turning what would have been negative half-cycles into more positive ones at the output. That’s precisely why we call it a mechanical rectifier.

- Follow one loop through one revolution (story mode)

- At start, one coil end is connected to the + brush, the other to the – brush. Coil EMF is small and positive → small positive DC at the terminals.

- As the loop nears 90°, induced EMF hits its maximum positive value. Same connection, so terminals see maximum positive voltage.

- As the loop approaches 180°, internal EMF wants to cross through zero and go negative.

- Right at that moment, the brushes pass over the gaps between commutator segments:

- Old segment moves away, new one comes under the brush.

- The coil ends effectively swap which brush they touch.

- Old segment moves away, new one comes under the brush.

- Result: the coil’s EMF reversed, and the coil leads to the brushes reversed → external polarity stays the same.

- The process repeats every half turn → external circuit experiences pulsating DC (always same polarity, but rising and falling).

- At start, one coil end is connected to the + brush, the other to the – brush. Coil EMF is small and positive → small positive DC at the terminals.

4. From ugly pulses to smoother DC: more coils, more segments

If you only had one loop and two commutator segments, your output would look like a full-wave rectified sine wave: all above zero, but very “bumpy.”

Real DC machines fix this by:

- Using many coils, placed at different positions around the armature.

- Giving each coil its own pair of commutator segments.

- Arranging them so the peaks of some coils’ waveforms fill in the valleys of others.

The more segments and coils, the more these waveforms overlap and the smoother the total output becomes. In large machines with many segments, the output is close to steady DC with small ripple rather than dramatic pulses.

- What improves DC quality in a commutator machine?

- Number of segments / coils

More segments → more overlapping waveforms → smoother DC. - Rotational speed

Higher speed → higher ripple frequency → easier to filter and often less noticeable. - Load characteristics

Inductive or capacitive elements can smooth or distort the waveform depending on the setup. - Brush width and placement

Wider brushes (over multiple segments) and proper positioning help reduce sparking and equalize currents during commutation. - Interpoles / compensating windings in larger machines

Added small poles help counteract armature reaction and improve commutation at varying loads.

- Number of segments / coils

5. Commutator vs electronic rectifier: same job, different era

Conceptually, a commutator is doing exactly what a diode bridge rectifier does in a power supply:

Find those portions of the waveform that would have been negative and flip them so they become positive at the load.

The big difference is how the flipping happens.

Mechanical vs electronic rectification

| Feature | Mechanical commutator | Electronic rectifier (diodes, MOSFETs, etc.) |

| What it is | Rotating copper segments + brushes | Semiconductor devices |

| Moving parts | Yes – rotor, brushes in sliding contact | No moving parts |

| Where it lives | On the shaft of DC generators & motors | In stationary power electronics circuits |

| How switching happens | Physical contact changes as shaft rotates | Junctions switch conduction based on voltage |

| Typical waveform handled | Armature AC → DC in DC machines | Mains AC or other AC → DC for loads |

| Limits | Wear, sparking, limited voltage & current | High efficiency; higher voltage/current possible |

| Maintenance | Brushes & commutator resurfacing periodically | Usually minimal |

| Modern trend | Declining use | Dominant in almost all new rectifier designs |

- Why we still care about commutators (and when we don’t)

- We care when:

- Studying DC machines in electrical engineering.

- Repairing legacy industrial DC motors and generators.

- Understanding universal motors (power tools, older appliances).

- Studying DC machines in electrical engineering.

- We care less when:

- Designing new EV drivetrains or industrial drives → we use brushless DC or AC machines with electronic commutation.

- Building modern power supplies → we use diode bridges, MOSFETs, IGBTs, etc.

- Designing new EV drivetrains or industrial drives → we use brushless DC or AC machines with electronic commutation.

- Still, the commutator is a perfect teaching tool for grasping the core idea of rectification.

- We care when:

6. Common misconceptions (and how to think more clearly)

Because commutators sit at an awkward intersection of “rotating hardware” and “signal processing,” explanations often get muddled.

One common confusion arises from statements like “the commutator converts DC to AC” or “AC to DC” without specifying where (inside vs outside). Some textbooks phrase it in ways that sound contradictory. A clearer—but slightly longer—statement is:

“In a DC generator, the armature develops an AC EMF, and the commutator converts that to DC at the external terminals by reversing coil connections every half turn.”

A related misconception: mixing up commutators and slip rings.

- Slip rings are continuous rings used to take AC off a rotating coil without changing its polarity.

- Commutators are segmented and are specifically designed to reverse connections and thus perform mechanical rectification.

- Misconception checklist

- “The generator itself makes DC”

→ Not exactly. The armature conductors generate AC; the commutator and brushes shape what you see as DC. - “Commutator changes the waveform shape inside the coil”

→ No. The coil still sees a sinusoidal EMF; we just change which coil end is called ‘positive’ at the terminals. - “Slip rings and commutators are basically the same thing”

→ Slip rings: continuous, no rectification. Commutator: segmented, deliberately switches polarity connections. - “Modern motors still rely on commutators everywhere”

→ Not anymore. Brushless DC and AC motors with electronic commutation have largely taken over in new designs because they’re quieter, cleaner, and more efficient.

- “The generator itself makes DC”

7. Where you’ll actually meet commutators today

Even though we’re moving toward brushless and electronically commutated systems, you can still spot commutators in the wild.

You’ll find them:

- In many older industrial DC drives and generators.

- In universal motors used in:

- Drills, mixers, vacuum cleaners.

- Some older washing machines and similar appliances.

- Drills, mixers, vacuum cleaners.

- In small DC motors in toys, hobby projects, and automotive components like starter motors and some blowers.

In all of these, the principle is the same: as the rotor spins, the commutator keeps re-wiring which coils talk to which brush so that external current stays in one direction.

- If you’re designing new equipment, why you probably won’t choose a commutator

- You can avoid sparking, which matters for:

- Explosive atmospheres,

- EMI-sensitive electronics nearby.

- Explosive atmospheres,

- You avoid brush wear and dust, which means:

- Less maintenance,

- Longer life, especially in sealed systems.

- Less maintenance,

- You get higher efficiency and speed using:

- Synchronous or induction AC motors,

- Brushless DC motors with electronic commutation.

- Synchronous or induction AC motors,

- You can avoid sparking, which matters for:

8. Closing intuition: the commutator as a “rotating bridge rectifier”

If you strip away all the copper, carbon, and steel, the idea is beautifully simple:

- The physics of a spinning loop in a magnetic field insists on producing AC.

- We then ask, “How can we wire things so the outside always sees the positive halves?”

- The commutator answers that by being a mechanically timed polarity switch, flipping the leads every half turn, so that what would have been negative halves become positive at the terminals.

Once you see it that way, a DC generator isn’t mysterious anymore. It’s just an AC generator plus a very clever, very physical rectifier bolted right onto the shaft.