Electric Motor Commutator Brushes: A Field Engineer’s View

If your commutator brushes are wrong, tired, or badly installed, the rest of the motor is mostly along for the ride. Brush grade, pressure, geometry, and environment quietly decide whether you get clean commutation for years or a burned-up commutator by next quarter. This article works on the assumption that you already know the theory and just want the decisions and patterns that actually stop failures.

Table of Contents

1. What Brushes Are Really Doing In Your Motor

Official documentation says: sliding contact, current transfer, carbon, graphite, copper. All true and already familiar.

In practice, the brush is managing three jobs at once. It has to carry current within a safe density window; it has to wear in a way that protects the commutator more than itself; and it has to build and maintain a stable film on the copper. The moment one of those three goes out of range, you start to see sparking, random discoloration, or noise on nearby electronics.

The awkward part is that those three jobs interact. Raise current density without changing spring pressure and the film burns in streaks instead of smoothing out. Tighten spring pressure without thinking about grade and you remove the film faster than it can form. You get clean copper, but ugly commutation.

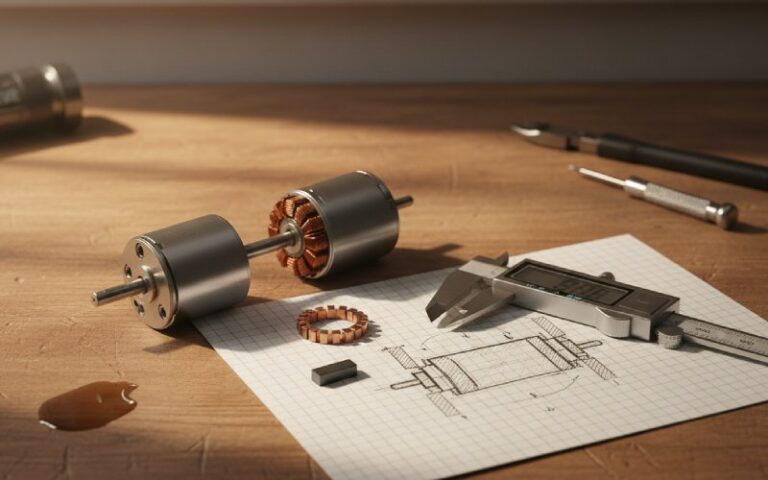

2. Design Choices Before the Motor Ever Runs

You already pick brush type and commutator design from catalog data and past projects. This section just nudges the choices where they usually go wrong.

2.1 Brush material and grade

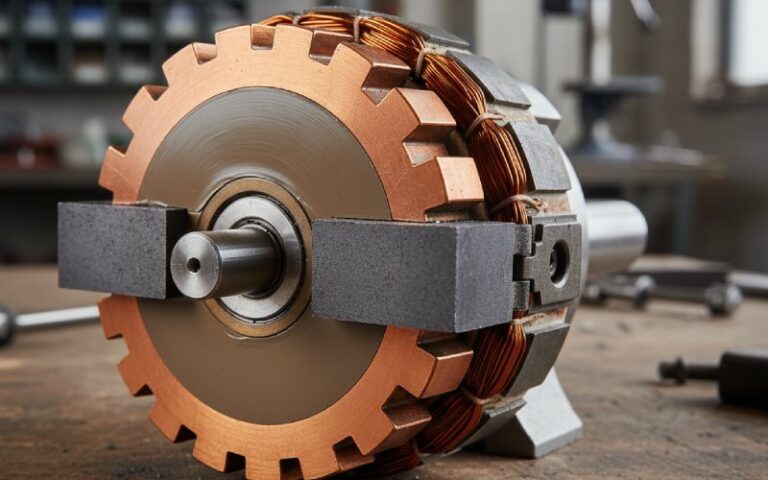

Most modern machines rely on carbon, graphite, or electrographitic grades, sometimes with metal impregnation for higher current density and lower resistance.

The usual trap is copying a “works everywhere” grade from another platform without checking surface speed and duty cycle. Electrographitic brushes might handle around 80 A/in² (about 12 A/cm²) continuously at surface speeds in the mid-thousands of feet per minute; push beyond that for long periods and the wear curve stops looking linear.

Another quiet trap is assuming metal-graphite always improves reliability in low-voltage DC drives. At modest voltage you sometimes just gain commutator wear: the brush runs cooler and harder, and the commutator pays the price.

2.2 Spring pressure

Spring pressure is one of those parameters everyone says “within spec” about, but almost no one measures in the field. Yet it directly splits mechanical wear (friction) and electrical wear (arcing) between brush and commutator.

Too low and the brush chatters, interrupts contact, and arcs. Too high and you grind carbon into dust, overload the commutator film, and run hotter than your life predictions assumed. The research and vendor guides frame total wear as the sum of mechanical and electrical components; spring pressure shifts that balance, not just “more or less wear.”

If you only remember one thing here: when you change grade, re-check the pressure. The “old” number is tied to the old friction behavior.

2.3 Commutator surface and geometry

Most guides say something like “not too rough, not too smooth,” which is true but not very actionable. Typical recommendations aim for a surface that gives the brush a proper seating base without glazing the film or shredding the edge.

A mirror-polished commutator often looks good but behaves poorly. The brush rides on a patchy film, local current density spikes, and you get streaks or banding. On the other hand, high mica or ridged bars act like a file. The brush face breaks into ribs, contact area fragments, and noise plus sparking follow.

2.4 Environment

Two things tend to be underestimated: humidity and contaminants.

High temperature and certain atmospheres intensify the interaction between brush graphite and copper atoms on the commutator, which speeds up wear on both sides.

Then there is silicone. Trace silicone in the air, sometimes under 1 ppm, has been shown to increase brush wear dramatically. It reacts in the contact zone, forming a poor film that is mechanically weak and electrically unstable. A motor working fine for years can start eating brushes soon after a new silicone-based lubricant or sealant appears in the same room. People often blame “bad batch” brushes first, and lose time.

3. Reading Brushes Like a Log File

The brush face and commutator surface tell you more than the nameplate. You probably know the classic signs; what matters here is the order in which you look at them.

Start with color and uniformity. A fine, evenly colored film on the commutator with equally colored brush faces usually means the grade, spring pressure, and environment are all roughly in balance. Random patches of bright copper with dark bands in between hint at intermittent contact or overloaded segments.

Next is wear pattern. One side worn more than the other often means brush holders are too far from the commutator or misaligned, so the brush cocks or vibrates. If the edges chip or the brush fractures near the connection, suspect either mechanical shock from vibration or brushes binding in the holder.

Then listen to the machine. Random crackling sound, not tied to load steps, usually lines up with brush bounce or rough bars. A more stable hiss can be normal for some grades at higher speed. The point is not to chase zero sound; it is to notice when the pattern changes.

4. Failure Modes That Keep Coming Back

Most articles list brush failures; real plants see the same subset over and over.

4.1 Sparking and bar burning

Sparking around the commutator is often blamed on “worn brushes” and stopped there. In reality, worn brushes are sometimes a symptom. Root issues include low spring pressure, poor seating, wrong commutation setting, rough surfaces, or carbon dust packed in the slots.

Bar burning tends to appear when sparking is local, not uniform. That points to individual bars with different resistance, damaged riser connections, or magnetic asymmetry. Brushes just reveal it first.

4.2 Rapid brush wear with a healthy-looking commutator

When brushes wear quickly but the commutator still looks acceptable, the grade and environment are usually mis-matched. High ash grades in a relatively clean machine tend to polish aggressively; low-ash grades in dirty air can let contaminant films build rather than control them.

If the plant has recently introduced silicone oils, greases, mold release agents, or sealants, that is a strong suspect. The lab data on silicone-induced wear is not subtle; life can drop by an order of magnitude.

4.3 Noisy commutation and EMI complaints

Random EMI problems near DC drives are frequently traced to brush noise rather than power electronics. Poor contact, uneven film, or brushes bouncing at particular speeds create narrow pulses that couple into nearby wiring.

Swapping filters on the supply side only hides the symptom. The quieter and more continuous the current transfer at the commutator, the easier it is to keep emissions under control.

5. Maintenance Habits That Actually Help

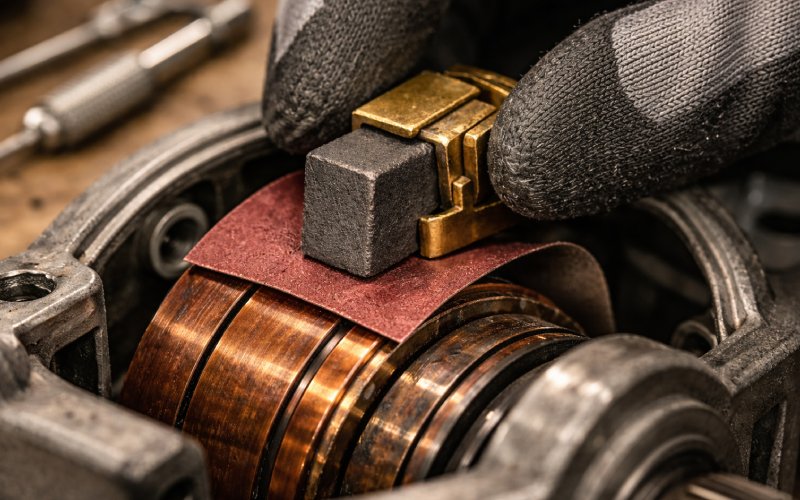

A lot of “maintenance” unintentionally damages brushes and commutators: aggressive sanding, wrong solvents, or fast brush changes with no seating. There are a few habits that consistently improve life instead of just making things shiny.

One is proper seating with garnet paper rather than generic sandpaper. Technical guides recommend wrapping garnet paper around the commutator or slip ring, rotating in the operating direction, and letting the brushes wear into matching curvature, then removing the paper only after lifting the brushes. This avoids embedding hard particles into the copper and gives you full contact area early in service.

Another is keeping brush holders close enough to guide the brush without letting it jam. Vendor guidance usually suggests a modest clearance from the commutator surface so the brush cannot tilt or chatter. When brush fractures reappear, measure that distance instead of only changing grade again.

Cleaning is more subtle. Mild solvents that are compatible with insulation and do not leave residues are preferred, and some manufacturers explicitly warn about certain chemical cleaners for environmental and safety reasons. Overcleaning with aggressive agents strips the film and resets the system back to “running-in” mode repeatedly.

Lastly, there is inspection frequency. Many plants stretch intervals based on early good performance. That works until the first commutator failure. Short, visual checks early in life tell you whether your initial assumptions about grade, pressure, and environment were right. After the machine has built a stable history, intervals can grow.

6. Quick Reference: Matching Brushes, Conditions, and Behavior

The table below is not a replacement for vendor data; it is a sanity check against common field observations. Values are indicative, not guaranteed limits.

| Brush type / grade pattern | Typical use case | Usual strengths | Typical traps in practice |

| Carbon / resin-bonded | Low-voltage DC tools, small motors, moderate speeds | Soft contact, gentle on commutator, quiet operation | Wears fast at high current density, film easily disturbed |

| Electrographitic | Industrial DC drives, traction, higher surface speeds | Handles higher current density and speed, stable film | Can wear commutator faster if pressure is too high |

| Metal-graphite | Low-voltage high-current, slip rings, starting duties | Low resistance, good current carrying at low voltage | Increased commutator wear, more sensitive to contaminants |

| High-ash grades | Dirty or variable environments, mining, heavy industry | Strong polishing, can control film under contamination | Can be abrasive if environment is cleaner than expected |

| Low-ash / special grades | Precision machines, sensitive EMI environments | Smooth commutation, low electrical noise | Film can be unstable in dusty or chemically active air |

7. Closing Thoughts

Commutator brushes look like small, cheap parts, but they are where your model of the motor meets the reality of the plant. Every change in grade, spring pressure, surface finish, or environment writes itself onto the brush face and the commutator film.

If you treat those surfaces as a running log instead of consumables to swap and forget, you get earlier warnings, fewer sudden failures, and less time arguing whether a bad batch or a wrong setting was to blame. The physics is well covered in the manuals and papers; the advantage now comes from noticing what your own machines are trying to show you.