Does a single phase motor have a commutator?

Usually no. If you are looking at the single phase motors that drive fans, pumps, blowers, and compressors, they are almost always induction machines with a squirrel-cage rotor and no commutator at all. The exceptions are specific “commutator-type” single phase motors such as universal, AC series, and repulsion designs.

Table of Contents

What most people really mean by “single phase motor”

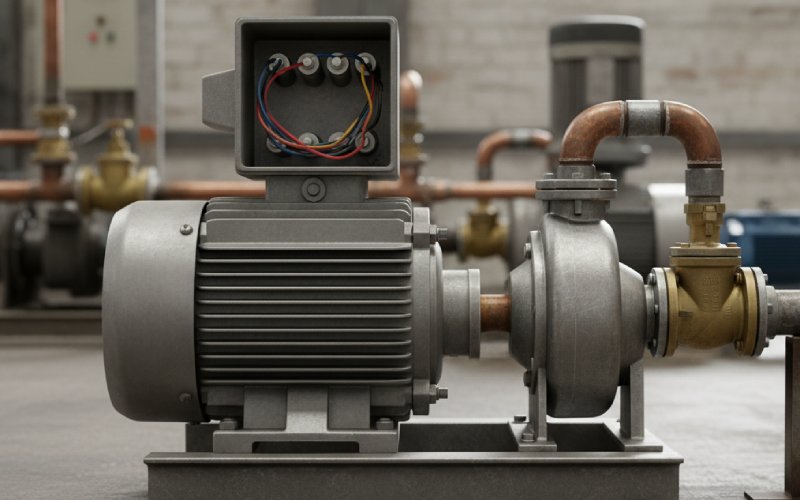

Out on site, when someone says “swap out that single phase motor,” they usually mean a single phase induction motor on 220–240 V AC. Capacitor-start, capacitor-run, permanent-split, shaded-pole – different starting tricks, same basic idea: stator on the mains, rotor as a closed cage, no brushes. The rotor never needs a direct electrical connection to the supply, so there is nothing for a commutator to do.

Historically, this is the design that replaced earlier commutator machines once engineers learned how to build a practical commutator-free single-phase induction motor and make it cheap and robust.

So if your question is really, “Does a typical single phase induction motor have a commutator?” the honest, boring answer is simply no.

But “single phase motor” is a fuzzy phrase

The phrase itself is lazy. It talks about the supply, not the construction. As soon as you cross from exam questions into real hardware, “single phase motor” can mean at least four different families:

A single phase induction motor on AC supply. A universal motor running from single phase AC or rectified DC. A repulsion or repulsion-induction motor, also fed from single phase AC. A DC motor sitting behind a rectifier, still ultimately fed from a single phase line.

Only the last three lean on a commutator. The word “single phase” doesn’t decide it; the rotor design does.

If you keep that straight, exam tricks and product datasheets both get easier to read.

Quick mental picture: what the commutator is really doing

The commutator is a rotary switch. Copper segments on the shaft. Brushes pressing on those segments. As the rotor turns, the connections of the armature coils are swapped around so that torque stays roughly in one direction, instead of flapping back and forth with the line polarity.

That function is vital in DC motors and in universal motors. It lets the rotor current keep the correct phase relationship with the stator field even while the supply flips polarity every half cycle. Without that trick you would just get vibration and heat. Or a very patient humming paperweight.

In a normal induction motor, you get that rotor current by induction, not by sliding contacts, so you “outsource” that hard work to the laws of electromagnetism. No commutator needed.

Where single phase motors genuinely have a commutator

There are a few well-defined cases where the answer flips to yes.

First, the universal motor. Electrically it is a series DC motor built with laminated iron and designed to live on AC as well as DC. The stator and rotor windings are in series, and the rotor uses a commutator so that when the supply reverses, both field and armature reverse together. Net torque does not reverse, so it keeps spinning the same way.

These are the motors inside handheld drills, many vacuum cleaners, small kitchen appliances, and a lot of cheap, noisy tools. High speed, high starting torque, small frame, and a commutator that wears.

Second, the family of repulsion and repulsion-induction motors. Stator looks like a single-phase induction stator. Rotor looks like a DC armature with a commutator and brushes, but the brushes are shorted together rather than connected to the supply. The resulting induced rotor currents create torque by repulsion between stator and rotor pole systems.

Some versions use the commutator only during starting and then short all segments together or lift the brushes, letting the machine run as a plain induction motor once it is up to speed.

So if you see a single phase motor frame with brush gear and a commutator on the shaft, you are almost certainly looking at one of those commutator-type designs, not a standard capacitor-start unit.

A simple comparison

Here is a compact way to keep the variants straight when you are staring at a confusing spec sheet or a dusty motor on a bench.

| Motor type | Supply description | Commutator present? | Brushes present? | Typical size range | Common applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single phase induction (PSC, CSCR, shaded pole, etc.) | Single phase AC only | No | No | Up to roughly 1 kW and beyond | Fans, pumps, compressors, small machinery |

| Universal (AC series) motor | Single phase AC or DC | Yes | Yes | From a few tens of watts to a few hundred watts | Hand tools, vacuum cleaners, kitchen appliances |

| Repulsion motor | Single phase AC only | Yes | Yes | Fractional horsepower | Legacy drives, specialised high-torque uses |

| Repulsion-induction, repulsion-start induction-run | Single phase AC only | Yes (for start, then often shorted or bypassed) | Yes (sometimes lifted at speed) | Fractional to small horsepower | Older machinery needing strong starting torque |

| DC motor on rectifier | Single phase AC into DC link | Yes (if brushed DC) or electronic commutation (if brushless) | Maybe | Wide range | Drives, servo systems, custom controls |

Once you classify the motor into one of these rows, the commutator question almost answers itself.

Why induction types avoid commutators on purpose

Designers move away from commutators whenever they can get away with it. The reasons are dull but persuasive.

Commutators and brushes bring wear, carbon dust, sliding contact losses, and sparking. They add machining steps, assembly steps, and maintenance instructions.

Induction rotors are just bars and end rings, usually cast aluminium or copper. No insulated segments. No brush rigging. The rotor is mechanically simpler and easier to balance. That is why shaded-pole motors at the very small end and capacitor motors at the more serious end became the default for “ordinary” single phase drives.

So when someone asks, “Could we use a commutator here?” the quiet follow-up is, “What are we gaining that justifies the cost?”

When a commutator single phase motor actually makes sense

It is not just nostalgia that keeps universal and repulsion-type motors around. They solve a specific set of problems reasonably well.

Universal motors give high starting torque and very high speed from a light, compact package on a simple AC line. That is exactly what you want in a handheld drill. You want strong torque from zero and you are happy to let the speed fall under load rather than spend money on an inverter. Noise is acceptable. Brush replacement is acceptable. The commutator earns its place there.

Repulsion and repulsion-induction motors are more of a historical answer to “how do we get high starting torque on single phase before we have cheap, large capacitors and solid-state drives?” They did that job using the commutator and brush geometry to shape rotor currents during starting. Later, designers could short the commutator once the machine was running and let the rotor behave more like a cage.

In modern catalogues you will see fewer of them, replaced by capacitor-start and electronic-drive solutions, but the principle is still worth understanding because old installations do not upgrade themselves.

How to tell at a glance whether your single phase motor has a commutator

On the bench or in the field, you often do not need instruments. Just your eyes and ears.

If the frame has brush holders, access plugs or a very obvious opening around the shaft line where brushes might be serviced, that is a strong hint. If you can see copper segments through a vent near the shaft, that is a commutator. If the manufacturer calls it “universal,” “AC series,” “repulsion,” or “repulsion-induction” right on the nameplate or documentation, you already know the answer.

By contrast, if the frame is smooth with only a terminal box or flying lead, no brush gear, and the plate says shaded-pole, capacitor-start, capacitor-run, or just “single phase induction motor,” you can assume there is no commutator hiding inside.

Noise is another clue. Universal motors tend to have a sharper, higher-frequency whine and more audible brush buzz. Induction motors on 50/60 Hz have more of a low hum plus mechanical noise from the fan and bearings.

A few subtle edge cases

Sometimes you will meet a motor that looks like a plain single phase induction unit, but the drive system in front of it makes the story messy.

One example is a DC motor fed from a single-phase rectifier and chopper. From the supply’s point of view that is “a single phase motor load.” From a construction point of view it is obviously a DC machine and will, if brushed, use a commutator.

Another example is a repulsion-start induction-run motor where the commutator segments are shorted or the brushes are lifted once it reaches speed. If you open it up at rest, you will see a commutator. If you model its steady-state running behaviour, you will treat it much like a cage induction rotor. Both descriptions are correct in their own limited way.

This is why the safest way to answer the original question is always: which specific single phase motor are we talking about?

Short direct answers to common variants of the question

Does a single phase induction motor have a commutator?

No. Its rotor is a cage (or occasionally a wound rotor with slip rings in larger three-phase machines, but not with a commutator), and rotor currents are induced. No brushes touching segmented copper.

Does a universal motor, running on single phase, have a commutator?

Yes. It is built very much like a DC series motor and uses a commutator and brushes as part of its normal operation.

Do repulsion-type single phase motors have a commutator?

Yes. They rely on a commutator and brush assembly to shape rotor currents for starting torque, even if that hardware is shorted or bypassed once the motor is up to speed.

Is the presence of a commutator a reliable way to tell AC from DC?

Not really. A universal motor is clearly an AC device but has a commutator. A DC motor with electronic commutation has no mechanical commutator at all. The better question is, “How is the rotor fed?” Directly through sliding contacts with switching segments, or entirely by induction or electronics?

So the honest summary is simple but slightly awkward: most everyday single phase motors do not have a commutator. Some specialised single phase motors absolutely do. The word “single phase” does not decide it; the rotor construction and torque-production method do.