Dirty Commutator Symptoms: The Practical Signals You Should Trust

If the commutator is genuinely dirty rather than just “used,” you usually see three things first: sparking that has changed character, brush tracks that stop looking uniform, and torque or speed that becomes less predictable under load. Everything else is just the story around those three.

Table of Contents

Dirty vs. Damaged: Why the Distinction Matters

Most manuals throw contamination, wear, and outright damage into one bucket. In the field, separating a dirty commutator from a failing one is the difference between a short shutdown and a rebuild. A dirty surface gives you inconsistent contact and patchy film, but the copper underneath is still fundamentally sound. The key is to read the symptoms before the dirt starts new failure mechanisms of its own. Guides from brush and motor manufacturers repeatedly point to irregular commutator surface, uneven film, and brush contact issues as early indicators of trouble, before catastrophic faults appear.

How Dirt Actually Shows Up At The Machine

You already know some arcing at the brushes is normal. What changes with a dirty commutator is the pattern of that arc. Technicians often notice brighter, more erratic sparking, sometimes concentrated on a few bars where the film is uneven or masked by carbon dust and grit. Excessive sparking is consistently cited as a sign of brush and commutator issues, especially when combined with contamination.

Then there’s the smell and temperature profile. A light warm odor after a heavy start is normal in many tools and starters. A dirty commutator tends to bring a sharper, repeated “hot carbon” or burnt insulation smell after relatively modest duty, often accompanied by localized heating at the commutator end of the frame. Field reports around failing armatures and brush gear mention smoke and burning smells as common symptoms, especially when the contamination has already pushed the system toward overload or shorted turns.

Noise shifts as well. A clean, bedded-in brush face tends to produce a steady hiss. When dust packs into the segments or grit rides between brush and commutator, that turns into a more granular rasp, sometimes with a rhythmic “tick” that follows shaft speed. You may also catch intermittent changes in speed or torque with the same load and supply, as contaminated sectors pass under the brushes and slightly mis-time current in the armature.

On DC drives and larger machines, the electrical side confirms what your ear has already told you. You may see more nuisance trips from overcurrent or ground-fault protection, or the need to back off armature current limits on the drive to avoid erratic arcing at the brush gear. Industry articles on damaged armatures and DC motor issues note that commutator faults and contamination can show up as increased arcing, hot spots, reduced efficiency, and protection trips long before a complete failure.

Symptom Map: What The Machine Is Trying To Say

The table below compresses how dirty commutators tend to present, assuming the machine was previously running acceptably. This is not a standards document. It’s the pattern many technicians quietly use as a first filter before deciding whether to clean, skim, or condemn.

| What you notice first at the machine | Likely commutator state | Quick field check that actually helps | Practical risk if you keep running it like this |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sparking stronger and more “spiky” than usual at a few locations around the brush track | Patchy film, local carbon build-up, maybe slight roughness | Kill power, rotate rotor by hand, inspect those bars with magnifier; look for dark streaks, tiny ridges, carbon packed in slots | Accelerated brush wear on a few tracks, growing hotspots, higher chance of flashover if load peaks or voltage rises |

| Uniform ring of bright sparks almost all the way around the commutator | Often beyond just “dirty”; could be severe contamination or armature short, insulation breakdown or bar-to-bar fault | Visual check for burning between bars; insulation tests if available. Several repair sources link this circular arc with shorted turns or bar faults rather than simple dirt. | High. Risk of flashover, commutator bar damage, drive trips, and possible collateral damage to brush gear |

| Brushes wearing unevenly, one side short, others still long | Uneven commutator film or contamination trail along one path, misalignment, possibly grit under one brush | Pull brushes and look at sliding faces; compare color and polish between positions. Industrial guides treat asymmetrical wear and streaked faces as strong hints of contamination or misalignment. | Rapid local wear, growing groove, potential for sparking and vibration as profile worsens |

| Distinct groove forming where the brushes track | Contamination embedded in the brush path, acting like an abrasive | Run a fingernail across the track with power off; if you clearly feel the groove, you’ve moved past light dirt into mechanical wear. Maintenance notes point to trapped grit as a common cause. | Reduced brush contact area, higher current density, more heat, and eventually the need for turning the commutator |

| Motor still starts, but requires more current or time, feels “lazy” under load | Contact resistance up due to carbon or oxidation film; some bars contributing less current than others | Compare armature current and temperature to baseline. Visual check for dull, patchy, or streaked surface with non-uniform color | Higher energy use, more heating; if ignored, this often evolves into burning on a few bars rather than all sharing the work |

| Occasional drive trips, especially on acceleration, paired with visible brush arcing | Combination of contamination, uneven film, and maybe drive settings that no longer match actual commutation quality | Scope on armature if available, or at least watch drive fault logs. Many modern DC drive notes mention excessive brush arcing as a clue that commutator or winding issues are present. | Intermittent production losses, potential for sudden failure if flashover or armature faults develop |

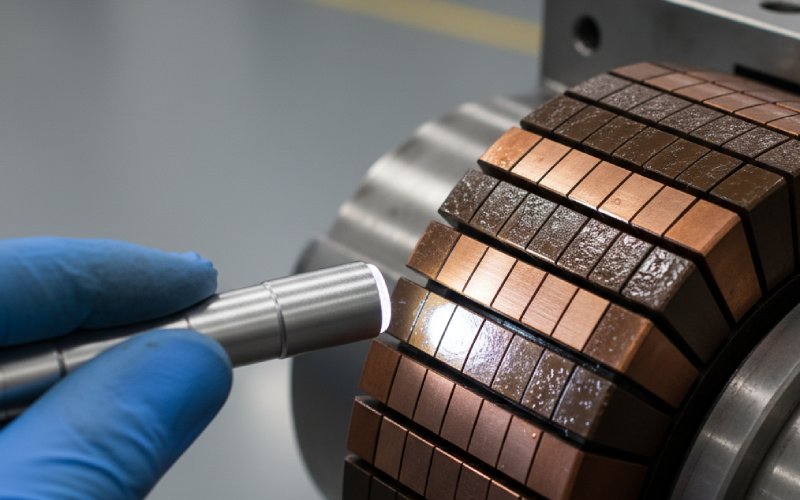

Reading The Surface: Film, Color, And Texture

Dirty commutators rarely look dramatic at first. What you see is usually subtle: film that is darker in patches, a slightly matte patch crossing several bars, or faint streaks trailing from under one brush. Condition guides from major brush manufacturers treat commutator irregularities and inconsistent film as primary early indicators, well before segments are clearly burned or ridged.

The practical habit is simple. When the machine is open anyway, you rotate the armature slowly and watch how the reflection of a light source moves across the copper. A clean, healthy surface gives a relatively uniform reflection, with only minor color variation from the film. Dirt and embedded dust break that pattern; the reflection stutters, the patina changes shade suddenly, or you see faint “witness marks” where debris has been dragged by the brush.

Texture matters just as much. A commutator can be electrically “dirty” with almost no visible dust if the film has become uneven or chemically altered. On the other hand, some heavy film patterns that look ugly still run acceptably because they are consistent and the brushes have adapted. This is where human judgment wins over any single rule: look for change relative to the last known good condition, not just for textbook pictures.

Separating “Needs Cleaning” From “Needs Turning”

Not every dirty surface justifies a lathe, but some do. A light, even discoloration with small amounts of carbon dust usually responds to cleaning and maybe a brush seating stick. Video and tutorial sources for basic commutator cleaning often limit their advice to fine abrasives and gentle methods, for good reason; once you start removing copper aggressively, you eat into commutator life.

Once there is a measurable groove along the brush path, or visible flats and steps between bars, you are not just dealing with dirt anymore. Over time, grit and carbon particles trapped between the brush and commutator can cut channels into the surface, a mechanism highlighted in maintenance articles on DC motor care. At that stage, cleaning alone may temporarily reduce arcing but will not restore the contact geometry, and the brushes will continue to wear in strange patterns.

A quick mental rule that many techs use goes something like this: if you can restore a uniform, lightly polished surface with minimal material removal and the machine then runs with stable current and modest sparking, you had a dirty commutator. If you need to take off enough copper to chase deep grooves or burnt bars, you are solving a deeper problem that dirt simply exposed.

Brush Clues You Should Not Ignore

Dirty commutators leave fingerprints on the brushes. Uniform, chocolate-gray faces with a smooth sheen usually suggest the film and surface are working. Patchy, streaked, or heavily chipped faces suggest foreign material, high spots, or both. Manufacturer wear guides explicitly use brush face appearance as a diagnostic of commutator health, separating “satisfactory,” “warning,” and “problem” patterns.

You also want to watch spring pressure and length. When contamination increases friction and heat, weak springs and short brushes lose the contest first. That is why many articles about sparking and worn armatures frame dirty commutators, worn brushes, and failing springs as a linked triad rather than separate issues.

If you pull a brush and see heavy, localized burning that lines up with a specific sector of the commutator, stop treating the case as a “dirty” one by default. That pattern often appears in armature or bar faults, which can coexist with contamination but are not cured by cleaning.

Cleaning That Respects The Machine

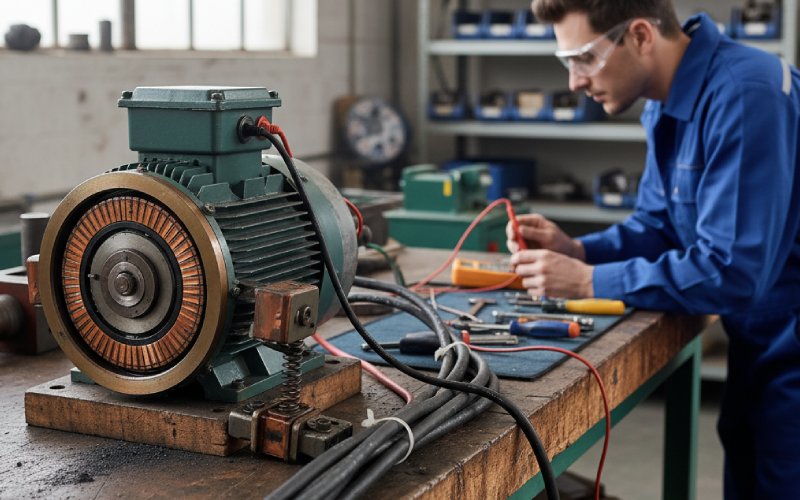

The techniques are already in most manuals: isolate power, lock out, pull brushes, clean out loose dust with air or vacuum, treat the surface with appropriate grade abrasive or commutator stone only if needed, re-seat brushes, and check spring operation. Guides on stopping brush sparking and cleaning commutators repeat the same ideas: use fine abrasives, keep debris out of the windings, avoid reshaping brushes aggressively, and restore a uniform contact pattern rather than chasing cosmetic perfection.

What actually differentiates a careful job is less visible. It is the decision to stop sanding as soon as you have uniform contact, not when every stain has vanished. It is the habit of inspecting the slots between bars for packed carbon and cleaning them properly instead of just shining the outer surface. It is the extra moment spent watching brush bounce at operating speed after reassembly, because a nominally clean commutator can still throw brushes around if geometry or balance is off.

When Dirt Is A Symptom, Not The Cause

Sometimes the commutator is dirty because something upstream is wrong. Overloading, misapplied brushes, poor cooling, or a misconfigured drive can all produce heat and sparking that break down the film and throw carbon everywhere. Industry notes on DC motor failures list overloaded or stalled motors, incorrect brush grade, and ventilation problems as root causes that eventually show up as commutator wear and contamination.

If you keep cleaning the same machine every few weeks and the symptoms keep returning, treat the dirt as data. Look for patterns in where the worst film forms, when the sparking peaks during the cycle, and how the current behaves. That pattern often points back to settings, duty cycle, or mechanical issues such as misalignment or vibration that shake the brush gear at certain speeds.

Practical Wrap-Up

Dirty commutators are less mysterious than they seem. They announce themselves early through small changes in sparking, brush appearance, and film uniformity. The skill lies in reading those changes and deciding whether you are looking at contamination on a healthy surface, or visible evidence of a deeper electrical or mechanical fault.

If you treat every dirty commutator as an excuse to skim copper, you shorten machine life. If you ignore the early symptoms and wait for a bright ring of arc and the smell of burnt insulation, you shorten it in a different way. The middle path is to treat the surface as an instrument panel: keep it clean enough to read, and use what it tells you to decide when to clean, when to re-machine, and when to stop and investigate the system around it.