DC Motor Brushes & Commutator – Wear, Problems and Maintenance

Most brush and commutator failures come down to four things: wrong brush contact, wrong surface condition, wrong environment, or nobody really looking at the machine until it is already upset. Everything below is about spotting those four early and correcting them with repeatable habits, not heroics.

Table of Contents

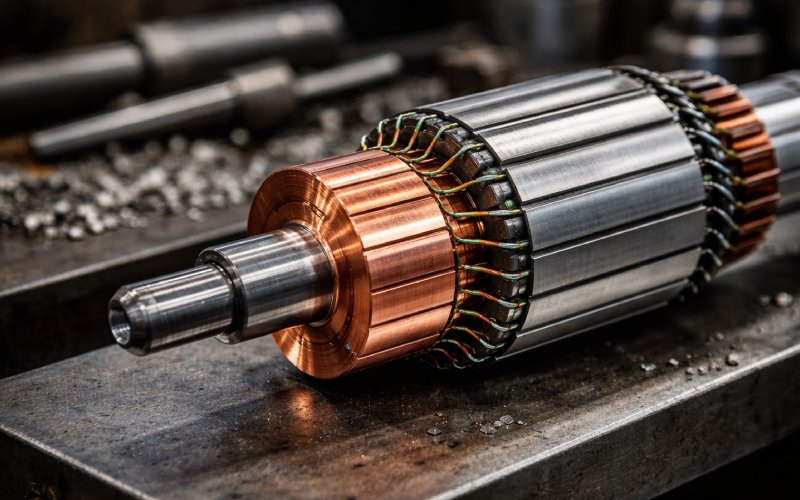

1. What actually wears at the brush–commutator interface

You already know the datasheet story: carbon brushes riding on copper bars, current switching, some neatly drawn current paths. Out on the plant floor the real interface is much messier and that is where reliability lives.

What actually “wears” is not just copper and carbon. It is the thin film on the commutator, the spring stack, the brush box alignment, the neutrality setting and the temperature profile of the armature. When the film is uniform, springs are in range, and vibration is under control, brushes wear slowly and predictably. When one of those drifts, wear rates jump, the pattern becomes uneven, and sparking appears long before the nameplate current is exceeded. This is why serious maintenance texts put so much weight on inspection of brushes, spring tension and commutator surfaces as the core of DC motor care.

The official manuals usually stop after “inspect, clean, replace.” The more useful habit is to treat every inspection as data collection: which zone is hotter, which brush holder is lazier, which direction the grooving runs, which bars are starting to stain. Over a few outages that data set becomes your local failure model for that drive, not a generic one.

2. Reading the commutator surface as a report card

The commutator face is blunt. It shows what has been wrong for the last few hundred hours, sometimes longer. Common surface conditions have fairly consistent causes, confirmed across many field guides and repair shops.

You will usually see one of these broad states:

A smooth, slightly satin ring with a thin, even, dark film that repeats on every bar is good news. The film has adjusted to the brush grade and duty, temperatures are sensible, and brush pressure is in the useful zone. You leave this alone, just keep it clean.

Grooves, thread-like lines, steps between zones, bar-edge burning, copper dragged in the direction of rotation, or patchy dark spots are middle-stage warnings. These patterns almost always mean mis-matched brush grade, contamination, overloads, poor neutral setting, or intermittent contact from vibration.

Then there is the emergency state: badly discoloured bars, heavy bar-edge burning, raised bars, mica proud of the copper, and metal transfer between adjacent bars. At that point you are not “maintaining” a commutator, you are recovering it.

Here is a compact correlation table you can use during inspections.

| Visual symptom on commutator | How it usually looks in the field | Likely dominant causes | First checks to make |

| Gentle, uniform dark film, smooth touch | Even colour all around, no bar edges visible by finger | Conditions matched to brush grade, current and cooling | Record as reference; confirm brush grade, spring settings, load profile |

| Grooving around the full circumference | Shallow slots, often mirror-like in the groove, step between brush tracks | Contamination, overly hard brush grade, high current density for long periods | Verify brush grade vs OEM, check air filtration, check armature current history |

| “Threading” or spiral lines | Fine helical lines in direction of rotation, sometimes with slight noise | Particles trapped under brushes, poor film, commutator slightly rough or eccentric | Measure runout, inspect air paths, confirm brush box alignment and freedom |

| Bar-edge burning / notching | Dark, burnt zones at leading or trailing bar edges, spark you can see in daylight | Neutral plane off, incorrect interpole settings, armature reaction, weak springs | Check brush position relative to neutral, verify spring force, confirm field / interpole currents |

| Copper drag in rotation direction | Smearing of copper, bars no longer sharply separated | Excessive temperature, overloads, high vibration, dirty film | Look for cooling problems, sudden load changes, bearing condition and imbalance |

| Patchy dark spots or pits | Local pitting, some bars clean, others very dark | Contaminants, moisture, inconsistent brush contact, occasional flash events | Check enclosure sealing, storage history, look for signs of past flashover at holders |

| Raised bars / high mica | Steps you can feel with fingernail, harsh brush noise | Mechanical looseness, thermal cycling, commutator not skimmed after heavy wear | Schedule machining and undercut; investigate overload or frequent start/stop duty |

No single row tells the whole story. The trick is to take the pattern, the recent operating history, and the environment together. Dirty mine air with groove marks is a different story from a clean test bench with the same grooves.

3. Brush wear patterns and what they usually signal

Brush wear is supposed to be boring. All brushes in a bank should be within a narrow band of length, faces with the same curvature, no chipping, no glazing, no edge burning. When that picture breaks, the pattern tells you more than the absolute length.

If one or two brushes in a holder group wear much faster than their neighbours, suspect uneven spring force, a tight box, a tilted holder or local commutator eccentricity. Field reports and repair notes consistently point to incorrect spring settings and wrong brush grade as root causes behind many brush–commutator issues.

If all brushes are short but uniform, with clean faces and acceptable commutator film, the problem is probably not electrical at all. That is simply normal wear and your replacement interval is too long or the brush grade is too soft for the duty.

Chipped edges, cracked leading corners and broken brush tails often point at vibration, either from the machine itself or the foundation. This link between vibration, sparking and eventual commutator damage is repeatedly highlighted in specialist notes on DC machines. Bad bearings, bent shafts, misaligned couplings and poor baseplates all show up as brush damage before the motor completely complains.

Glazed, shiny faces with low wear and poor current sharing often indicate low current running, very light loading, or lengthy idle rotation with excitation. The film grows harder and smoother than the brush likes and contact becomes unreliable. In such cases you may need a slightly softer grade or a deliberate cleaning and running-in after extended light-load operation.

4. Electrical symptoms: sparking, noise and flashover risk

Sparking is the obvious symptom, but the timing and distribution of that spark is what matters. Light, evenly distributed sparking under heavy load can be acceptable for some machines. A few heavy, roaming sparks on specific brushes at moderate load is a much more serious warning.

Excessive sparking has a short list of usual suspects across most DC motor guides: worn brushes, incorrect spring pressure, dirty or rough commutator surface, mis-set neutral plane, or overload. If the spark follows a particular holder position, you focus on alignment and local surface quality. If it follows load, you look at current density, interpole settings and thermal behaviour.

Flashover is less common but costly. EASA’s technical notes make it clear that sharp bar edges and high voltage stress at the commutator end are strong contributors, and that simple geometry changes such as chamfering bar edges can markedly reduce stress and risk. Add contamination, high humidity, and a weak or damaged brush rig and the probability climbs.

Electrical noise and radio interference from a DC drive also often track back to poor commutation. When someone from controls complains about noisy signals, include brush and commutator condition as part of that investigation instead of treating it only as a filtering or shielding problem.

5. Maintenance routines that keep things boring

Most high-quality references on DC motor care say roughly the same thing: reliability is dominated by regular human inspections of brushes, brush gear and commutator, not by clever one-off repairs.

A practical pattern many plants move toward looks like this, even if they do not write it exactly that way. Short, frequent looks while the machine is stopped. Periodic deeper inspections with covers off and records taken. Occasional heavy work such as machining, undercutting and full brush replacement, ideally planned instead of forced by a trip.

On the light end, a short outage inspection should check at least: brush freedom in the box, cable tails intact, spring arms not sticking or seized, visible commutator zone under each brush bank, and the general cleanliness of the interior. You are not trying to fix anything at this point; the goal is to see how the machine has been living since the last visit.

On a scheduled deeper outage, you add: measuring brush length and recording min/average/max by holder; measuring spring pressure with a gauge; inspecting commutator runout and surface roughness; checking mica depth and condition; checking brush holder alignment and stagger; inspecting main and interpole connections; and cleaning out all embedded dust from ducts and cavities. Notes from carbon brush manufacturers strongly emphasise that thorough cleaning and inspection of commutator and slip ring areas is one of the best ways to avoid early commutation issues, and that pitting or dark patches at bar edges are early warnings that should be addressed before they grow.

After any heavy intervention, like skim cutting a commutator or changing brush grade, you build in a careful running-in phase rather than dropping the motor immediately into full production duty. That is the part most schedules forget and where many repair jobs quietly lose value.

6. Practical numbers and tolerances

Practitioners often argue about exact values, but a few numeric guidelines tend to repeat across technical notes and manufacturer recommendations.

Brush replacement length is commonly set around half of the original length. Many modern maintenance guides suggest inspecting brushes every 500–1000 operating hours for general-duty machines and replacing them before reaching the manufacturer’s minimum length, not when they are almost gone. In dirty or high-load service, you bring those intervals in sharply.

Spring pressure is usually specified by the brush supplier, often in the range of a few tens of kilopascals on the contact area. Too low gives sparking and erratic film; too high increases wear and heating. The important part is to actually measure the pressure with a gauge during outage, not just assume the springs are “still stiff enough.”

Commutator runout, roughness and mica depth have their own OEM numbers, but the rule of thumb is simple: if you can clearly feel bar steps or proud mica with a fingernail, you are already outside the sweet zone and on your way toward poor commutation. Repair notes emphasise that evident mechanical damage, spark burns or an unsmooth surface should be corrected by machining or grinding, followed by undercutting and cleaning, rather than just by “extra cleaning.”

Temperature is another quiet limiter. Brush gear running much hotter than adjacent steel structures usually means either high current density, poor cooling or excessive friction. A handheld infrared thermometer or thermal camera during a steady load run can reveal hot spots at holders or on the commutator face long before the winding temperature alarms.

7. After a repair or long shutdown: bringing the motor back

Brush and commutator problems often show up right after something changed. A rewind, a new VFD front end, a long storage period, a brush grade change. So the first few hours back in service matter more than usual.

After long storage, especially in damp or contaminated environments, many manufacturers recommend cleaning the commutator, checking for dark patches or pitting, and separating the brushes from the rotating parts with insulating material until you are ready to run again. Once you recommission, do not skip film rebuilding: a controlled run with gradually increasing load lets the brush–commutator interface rebuild its working surface instead of tearing itself into shape under full torque demand.

When you change brush grade, make it a documented experiment rather than a quiet swap. Record the old grade, hours, surface condition, and sparking behaviour. Install the new grade, perform a proper bedding-in (hand stoning or low-load running as per supplier guidance), and then re-inspect after a known number of hours. Without that loop, you never really know whether the new grade helped or just moved the failure mode somewhere else.

After commutator machining, undercutting and heavy cleaning, plan several short load runs with inspections between them. Look at film development, sparking level, brush seating and temperature. It feels slow, but rebuilt commutators that are thrown straight into hard duty are exactly the ones that come back burned in the next outage.

8. Short summary for busy engineers

If you strip away the jargon and long checklists, reliable DC motor brush and commutator operation boils down to a few habits.

Keep the environment clean and predictable so the film can stabilise. Keep the mechanical parts aligned, free to move and within runout and spring limits. Watch the visual patterns on the commutator and brush faces and log them with dates, loads and temperatures. Intervene early when those patterns shift, using machining, brush grade adjustments or cooling fixes rather than waiting for trips and flashovers.