Commutators in Renewable Energy Applications and Small Wind Generators

Most large wind and solar plants quietly abandoned commutators years ago. Yet in the low-power corners of renewables – backyard turbines, bridge-mounted micro-wind, hybrid DC systems – mechanical commutation still solves real problems. If you treat the commutator as a designed, monitored consumable rather than an awkward relic, it can give you simple DC, low cut-in speeds and compact hardware that power electronics alone sometimes struggle to match.

Table of Contents

Where commutators actually appear in renewable energy systems

If you only look at utility-scale projects, it seems as if commutators are gone. Mainstream wind farms rely on synchronous generators, doubly fed induction machines or direct-drive permanent magnet machines, all without mechanical commutation, because brushes and segmented copper rings add cost and reduce reliability at megawatt scale.

Zoom in to a few hundred watts or a few kilowatts and the picture shifts. Permanent-magnet DC generators with commutators still power small stand-alone wind turbines, especially where the load is physically close and fundamentally DC: battery banks, low-voltage heaters, LED lighting, embedded electronics on bridges or roadside poles. These machines ride on a few simple facts the datasheets underplay. Mechanical commutation gives you native DC; the commutator segments and brushes are, effectively, a built-in rectifier and current direction switch. The machine can start producing usable DC at low shaft speeds without needing an active rectifier or boost converter just to wake up the system.

There is also a grey zone between classical DC machines and more exotic harvesters. A recent axial-type wind energy harvester uses a commutator arrangement to reorganize phase connections in a way that beats diode rectification at low speed, increasing output power by factors of four to sixteen compared with straightforward rectifier solutions. This is not nostalgia; it is engineers using mechanical commutation as another optimization variable in a very constrained low-power budget.

So the modern renewable toolbox is mixed. At one end, fully brushless machines plus converters. At the other, PM DC generators and even improvised brushed alternators from automotive hardware. In between, research devices that treat commutators as part of the power-conversion strategy rather than just a legacy feature.

Mechanical commutation versus power electronics

The basic trade-off is not mysterious: put complexity in copper and graphite, or push it into silicon and software. Papers on electric machines for renewables are plain about the downsides of commutators: torque ripple, current ripple, speed limits, friction, electromagnetic interference, and the need for periodic maintenance. That is why large wind switched to brushless architectures and power converters years ago.

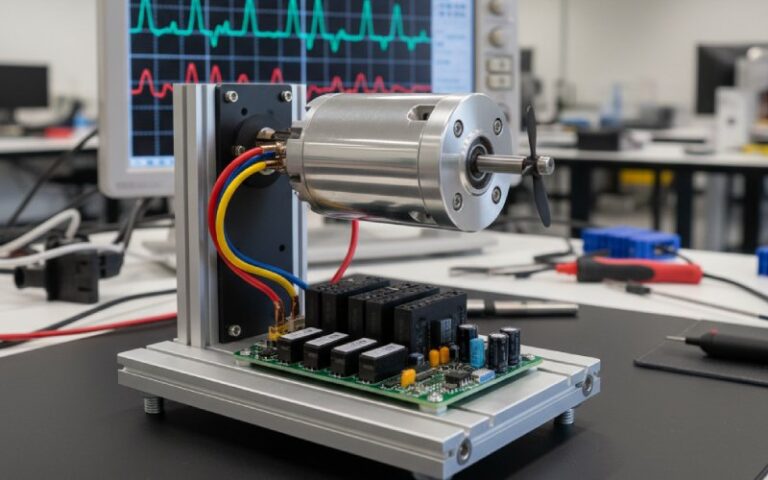

But in small wind and micro-renewables the balance is more subtle. Imagine three architectures for a 500 W turbine feeding a 24 V battery bank. One: a PM DC generator with commutator, direct-connected to the battery through a simple charge controller that mostly enforces voltage and current limits. Two: a low-speed PM alternator, three-phase, rectified and then fed through a DC-DC converter with maximum power point tracking. Three: a switched reluctance generator with sensorless control and a multi-phase converter. The first has a mechanical bottleneck and cheap electronics; the last has almost no rotor copper and plenty of software.

When wind speed just nudges the blades into motion, the commutated PM generator produces a lumpy but useful DC current as soon as the back-EMF rises a few volts above the battery plus the brush contact drop. In contrast, the PM alternator might need enough speed to bias its rectifier and for the converter to boot and start switching. At the same time, the commutator is generating ripple and brush noise, which a grid-connected system cannot tolerate but a nearby lead-acid bank really does not care about.

In other words, mechanical commutation trades sophistication in control for tolerable inefficiency and wear. This trade is not “old versus new”; it is a question of how often a human can visit the turbine, what kind of loads sit on the DC bus, and how much you are willing to spend on converters that will eventually fail in their own ways.

Where commutators make sense in small wind

Small wind lives with messy wind profiles, gusts that barely overcome static friction, and long periods just above cut-in speed. PM DC generators with commutators often do well here, especially at a few hundred watts, because their no-load voltage rises quickly with speed and they can be wound for generous EMF at low rpm without worrying about rectifier characteristics.

There is also the “distance to the load” question. When you run thirty or forty meters of cable from a pole-mounted turbine to its batteries, running native low-voltage DC at high current is unpleasant. Many designs then shift toward AC machines with rectifiers located near the batteries, so the long run is at higher voltage and lower current. For micro-systems with cable runs of a few meters on a bridge or a rooftop, that argument weakens. The commutator machine can sit a meter from the batteries with minimal wiring loss, and the brushes are accessible for replacement without climbing a tall tower.

In unelectrified regions or distributed infrastructure (roadside equipment, remote monitoring), you sometimes want locals to service the turbine with hand tools rather than oscilloscopes and firmware updates. Swapping brushes and cleaning a commutator slot with a stick and a bit of fine abrasive is a skill that can be taught without any programming. That sounds minor until a 200 W turbine powers something critical and sits three hours of rough driving away from the nearest technician.

The brush–commutator unit as a designed subsystem

Official datasheets usually treat the commutator and brushes as a compact black box: rated current, nominal voltage, maybe a generic maintenance interval. Real performance and life depend on details. That includes film formation on the copper surface, contact pressure, humidity, airborne contaminants, and subtle geometry choices.

A good commutator in small wind does not just “avoid sparking.” It builds a stable, slightly resistive film on the bars that lubricates the interface, spreads current, and suppresses micro-arcs. The brush grade needs to be chosen so it wears at a rate that protects the copper, not the other way around. Carbon brush technical guides emphasize that the brush should be the sacrificial part; excessive metal wear usually points to the wrong grade, bad stagger, pollution or incorrect mica undercutting.

There is now serious analytical work around the reliability of brush–commutator units. One recent study models the residual life of motor brushes using statistical classification of failure types and wear extent, with the goal of predicting remaining life more reliably than simple operating-hours counters. Translating that to small wind is straightforward: measure current, temperature, maybe shaft speed; learn the signatures of abnormal wear; trigger cheap predictive maintenance before the turbine is needed in a storm.

Small turbines usually do not justify full vibration monitoring systems, yet a minimal set of sensors can still support condition-based maintenance of the commutator. A hall sensor for speed, a shunt for current, and a microcontroller that notices when current ripple or brush voltage drop drifts beyond a historical envelope – that is enough to flag “send someone with brushes on the next routine visit.”

Environmental and application constraints that shape commutator design

Renewable environments are not laboratory clean. Small turbines sit in salty air, desert dust, insects, and sometimes the very vehicle-induced airflow that generates the energy. In bridge-mounted systems, particulate from vehicle exhaust mixes with moisture and forms conductive deposits. The commutator–brush interface must tolerate this while keeping stray leakage currents away from control electronics.

Brush pressure is usually chosen as a compromise between contact resistance, mechanical wear and tracking stability under vibration. For small wind, dynamic loading is worse than in many industrial drives: gusts, tower sway, yaw movement. Spring systems that are fine on a bench can lose contact on the leading edge of a gust, creating repeated arcing just as torque spikes. Standard tables for “brush pressure versus current density” are useful starting points, but field data in the intended wind regime is what actually closes the design loop.

There is also the noise issue. In tiny energy harvesters with commutators, acoustic noise may be irrelevant. On a residential rooftop, the ticking and variation in torque can matter to neighbors. Designers often mitigate this not with exotic mechanical tricks, but by rethinking the commutation pattern and smoothing the electrical loading through modest capacitors or inductors so that torque steps are muted without over-stressing the brushes.

Comparing generator options for small wind

Most “which generator is best” comparisons for small wind gloss over the presence or absence of commutators. They focus on power curves and cost. Yet for a design engineer or technically inclined builder, it helps to think of the commutator as a system-level feature.

Here is a compact comparison of common machine types in the small-wind range and what the commutator (or its absence) does to the overall system. Values are indicative rather than universal.

| Generator type | Typical small-wind power range | Commutator present? | Notable strengths in renewables context | Main drawbacks in renewables context | Typical present-day use case |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Permanent-magnet DC generator | ~50 W – 2 kW | Yes | Native DC output, low cut-in speed, simple electrical interface to batteries and DC loads, can be repurposed from automotive units | Brush and commutator wear, torque and current ripple, limited maximum speed, requires access for maintenance | Off-grid battery charging, educational turbines, small hybrid PV–wind systems with nearby loads |

| Low-speed PM synchronous generator (brushless) | ~300 W – 20 kW | No | High efficiency, no brush wear, compatible with grid-tie inverters, good for direct-drive turbines | Needs rectifier and often a DC-DC or inverter stage, higher up-front cost, more complex control | Small to medium direct-drive wind turbines, including backyard units with commercial inverters |

| Doubly fed induction generator (DFIG) | >1 MW traditionally, but principles scale down | Slip rings only (no commutator) | Variable-speed operation with partial-scale converters, established technology in large wind | Complexity not justified at very small scales, slip-ring maintenance still needed, usually overkill for micro-systems | Utility-scale wind turbines with grid connection |

| Switched reluctance generator | ~500 W – many kW (mostly research in small wind) | No | Simple and robust rotor with no magnets or windings, good fault tolerance, wide speed range | Requires sophisticated power electronics and control, acoustic noise can be significant, limited commercial availability | Experimental and niche wind systems where robustness and magnet-free design are priorities |

The point is not that the commutator machine is “better” or “worse.” It shifts where complexity sits. The PM DC generator uses mechanical means to approximate what a rectifier and some control logic would otherwise do; the brushless options move nearly all cleverness into silicon and software.

Control and protection details that often get skipped

In small wind design notes you sometimes see a simplified picture: turbine, generator, rectifier, battery. With a commutated machine that diagram hides several issues that only appear in prototypes and failed field units.

First is brush voltage drop. As brushes wear and the film changes, the effective voltage at a given current shifts. For a battery-connected DC generator, that changes the operating point on the turbine’s mechanical curve. At high current, a few tenths of a volt of extra drop per brush pair can be the difference between stable operation and a stall at awkward wind speeds.

Second is overspeed behavior. Brushless machines frequently rely on converter-based braking or pitch systems. A small commutated generator might instead use electrical loading and simple furling or mechanical braking. That means the commutator has to tolerate transient currents during gusts and emergency stops, including the associated arcing when current is interrupted. If you size the machine only around “rated current at rated wind,” you risk copper bar heating and surface damage in just a few severe gusts.

Third is electromagnetic compatibility. Brush commutation produces broadband noise. A short DC cable from turbine to controller acts as an antenna. In micro-systems that share power with sensitive electronics (sensors on a bridge, communications hardware in a remote node), the generator may need extra filtering beyond a token capacitor across the terminals. If you know from the start that the machine will sit next to radios, you can plan brush layout and wiring geometry to reduce loop area and radiated noise, instead of trying to fix interference in software later.

A slightly messy but realistic way to think of it: every commutator is an uncontrolled multilevel converter built from copper, graphite, and air, with its own switching pattern dictated by rotor position and brush width. The job of the rest of the system is to keep that uncontrolled converter inside a region where it behaves acceptably for both the electrical and mechanical parts.

Maintenance economics and planning

From a purely academic view, the friction losses and maintenance of commutators make them unattractive in renewables. Yet market analyses still note demand for high-performance commutators, partly due to growth in electric motors and a share of applications in renewable and industrial systems running under continuous load.

The economic story in small wind is often about cash flow and logistics rather than peak efficiency. A PM DC generator with a commutator might lose a few percentage points of efficiency compared to a brushless alternative. Over a year, on a 300 W turbine in a moderate site, that might mean tens of kilowatt-hours difference. Meanwhile, the cost of a replacement brush set and a quick cleaning visit every few years is modest, especially if the same trip services multiple units.

Where this fails is when access is genuinely hard or safety critical. Offshore, on high towers, near traffic with lane closures, or on structures where any maintenance requires specialized equipment, the cost of a brush visit dwarfs any savings in power electronics. That is why offshore wind almost exclusively uses brushless solutions with high-reliability slip rings only where absolutely necessary.

On the other side, in bridge-based or roadside micro-generation, crews already visit for lighting, inspection and other work. Cleaning a commutator and replacing brushes becomes an extra task, not a dedicated operation. In those environments the commutator’s maintenance cost folds neatly into existing routines, which shifts the balance back toward brushed machines, particularly where budgets are tight and grid connection is absent or fragile.

Where this is heading

Research directions in wind and hybrid systems keep pushing away from mechanical commutation: direct-drive PM machines, switched reluctance generators, axial-flux designs with sophisticated power electronics, and hybrid grids where DC buses connect multiple converters. Commutators are becoming rarer in mainstream renewable deployments for good reasons.

Yet they are not disappearing overnight. Improvements in brush materials, better understanding of film behavior, and diagnostic methods that estimate remaining brush life from operational data all stretch service intervals and reduce the risk of abrupt failures. In parallel, niches such as micro-wind on infrastructure, experimental harvesters, and retrofits of existing DC machines still benefit from the simplicity of mechanical commutation.

For designers and technically minded users of small wind generators, the useful mindset is neither “commutators are obsolete” nor “commutators are always cheaper.” It is more direct: a commutator is one more power-conversion device in your system. It wears, it adds ripple, it simplifies other hardware. If you accept that and design the rest of the system around its real behavior – including monitoring, access, and noise – it can still be the right choice in a surprisingly modern renewable project.