Commutators in Automotive DC Motors: Window Lifts, Fans, and Pumps

Commutators in cars rarely fail overnight; they age into problems. In window lifts, fans, and pumps, the same copper and carbon decide how the vehicle feels to use, how noisy it is, and how often parts come back under warranty. This article is about those decisions, not the textbook diagrams.

Table of Contents

Why commutators in cars are still everywhere

Modern cars carry a surprising number of brushed DC motors with commutators: window lifts, seat adjusters, blowers, mirror actuators, small pumps. Some suppliers openly note that a mid-range car can host dozens of commutators, each tied to a comfort or safety function.

Even as brushless drives expand, brushed motors stay attractive in low-power 12-volt functions because the electronics are simple, the control is trivial, and the motor is cheap to package. Technical articles on DC machines still treat the commutator as the standard way to reverse armature current in small motors, even though high-power drives have moved on.

So the real question for an automotive engineer is not “commutator or no commutator?” It is “what does this little ring of copper have to survive in this role?”

Window lifts, HVAC blowers, and small pumps are good examples because they share a common 12-volt supply and basic motor topology, yet their commutators see very different mechanical, thermal, and environmental stress.

Same copper, three jobs

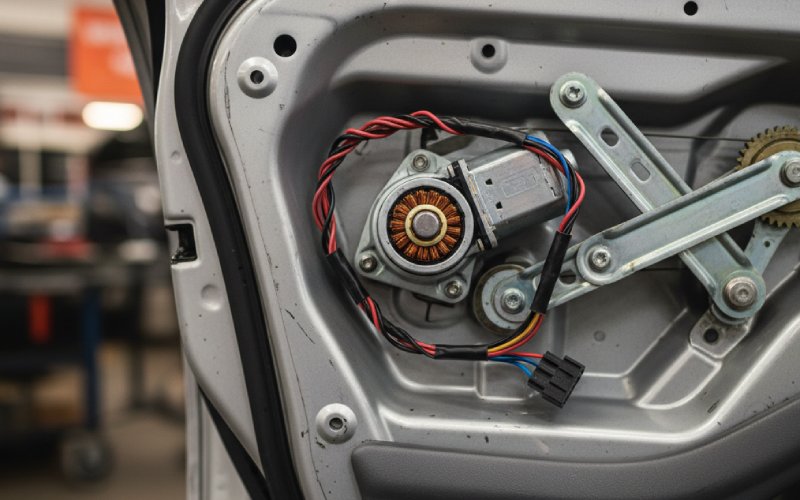

Most automotive commutators aimed at these functions are molded copper-segment designs: several copper bars arranged on a plastic hub, insulated with mica or resin systems, clamped to a steel shaft, tied into the armature windings.

Brushes are almost always carbon-based, sometimes with copper content, loaded by springs to keep contact across a few segments at once. The sliding interface is where every unpleasant thing happens: arcing, brush dust, local heating, chemistry with vapors and moisture. Practical guides on brush life are blunt about it: most DC motor failures trace back to this region.

Where the three applications differ is not the drawing, but the life the drawing has to live.

Window lifts work in short bursts, often near stall, sometimes abused as “extra door handles.” Fans run for long periods at partial load, rarely stalled, with airflow adding cooling but also spreading carbon dust. Pumps sit in or near fluids and can see long idle periods, then harsh starts in a wet, sometimes chemically aggressive atmosphere.

The commutator design ends up reflecting these lives more than any marketing spec sheet does.

Window lift motors: short bursts, brutal stalls

Window lift commutators are compact, often with a relatively small outer diameter to fit inside crowded door modules. Specialized manufacturers describe them as tailored components for power window systems, focusing on controlled movement rather than continuous duty.

The duty cycle looks gentle on paper. A few seconds up, a few seconds down, lots of time off. Reality is different. The motor is routinely driven into mechanical stops, pinched by ice in winter, dragged by window seals that stiffen with age. Smart regulators limit current and detect pinch, but they do it after the commutator has already seen that high current event.

Arcing and NVH

Research on window-lift gear motors shows that the contact between carbon brushes and commutator generates broadband noise that feeds directly into gear vibration and handle feel.

That noise has two components. One is mechanical: brush bristle chatter, segment edges, gear backlash. The other is electrical: rapid current transitions at the commutating segments. Each badly timed micro-arc leaves a mark on the copper, and those marks slowly change the sound of the mechanism.

You can see this on long-term test parts. Fresh commutators show a smooth, almost mirror finish. After endurance, a window lift that has seen many high-load events carries patchy dark tracks, distinct high-energy bars near the typical stall position, and often a slight step where brushes have worn a groove. All of that feeds back into both noise and brush wear.

Bar count and compromise on direction

Window lifts must run quietly in both directions. That sounds routine, but the brush lead angle that gives clean commutation in one direction is never perfect in the other.

A higher bar count can reduce torque ripple and lower bar-to-bar voltage, which helps arcing, but it also shrinks each segment. Too small and you fight manufacturing tolerances, brush seating trouble, and contamination bridging. Too large and the window feels rough and stops are harsh. The sweet spot is application-specific and often found empirically, not by the neat equations in the motor theory chapter.

More awkwardly, repeated stalls tend to happen in similar rotor positions. That means the same few bars carry disproportionate abuse. On teardown, it is common to find two or three burnt bars on an otherwise healthy commutator from a window motor that customers complain is “slow” or “noisy,” long before the brushes reach end of life.

Moisture and door life

Door environments are humid, dirty, and mechanically brutal. Water paths through the glass seal, condensation in the door cavity, temperature swings between garage and winter road — all of this affects the brush–commutator interface. General DC motor references highlight that moisture, dust, and oil increase commutator wear and can destabilize brush films.

In practice, that shows up as motors that run perfectly on a bench at room temperature but misbehave inside the door after a cold night. A thin oxide or contamination layer forms on the commutator; the first movement of the day scrapes it off with more arcing than usual. If the brush springs are marginal, you get bouncing, micro-pitting, and a little more copper dust in the housing each time.

HVAC blowers and cooling fans: long hours at moderate stress

Blower and fan motors live a different life. They usually spin freely, rarely stall, and often run for long periods whenever the climate system is active. Time-at-temperature, not peak current, drives their design.

Guides on brush wear talk about three big levers: current density, surface condition, and environment. In a blower motor, current density is moderate, the surface stays relatively clean, and the air flowing through the housing gives a little free cooling. That shifts the focus to ensuring stable brush film and avoiding patterns that lead to resonant noise.

Thermal life and commutator geometry

Because blowers spend hours at part load, the commutator must tolerate a steady stream of modest heating instead of short bursts of heavy heating. Copper segments see fewer extreme hotspots but more cumulative diffusion and oxidation. The plastic hub and resin insulation age from temperature more than from mechanical shock.

Geometry choices reflect that. Bar count is often higher than in tiny window motors, to support smoother torque at higher speeds and lower electrical noise. Segments may be skewed or paired with skewed armature slots to prevent cogging and reduce amplitude peaks in the acoustic spectrum.

At high fan speeds, the brush track is effectively a sliding wear test at several thousand surface meters per minute. Any mismatch between brush grade and commutator surface hardness shows up quickly as streaking, ridging, or rapid diameter loss.

Noise priorities

HVAC systems already make airflow noise. So the motor’s own acoustic contribution gets some masking. On the other hand, customers hear “tick tick” and “whine” right behind the dashboard, so tonal features still stand out.

Broadband hiss from brush noise is usually acceptable if it stays within the background of air rush. Distinct tones from slot passing and commutation irregularities are less acceptable. That drives tighter control of commutator roundness, segment height, and brush spring symmetry. The NVH task for blowers is not to be silent; it is to blend.

Pumps: fluid, contamination, and commutator survival

Small automotive pumps cover washer fluid, some coolant boosters, some fuel supply roles, and plenty of aftermarket devices. Many still use brushed DC motors with commutators, although the trend in fuel delivery at least is moving toward brushless units for efficiency, durability, and better fuel compatibility.

Here, the commutator’s enemy is not only current and heat, but fluid and chemistry.

Fuel pumps and wetted motors

Technical discussions around fuel pump design point out a simple rule: running brushed DC motors submerged in some fuels, especially low-lubricity diesel, can accelerate brush and commutator wear.

Fuel can wash away the delicate graphite film that normally stabilizes contact, leaving metal more exposed. In some fuels, poor lubricity and additives combine with electrical stress to erode brush edges and pit the copper. If the motor is not submerged, seals take the punishment instead; when they leak, fuel reaches the commutator in a way the design never intended.

The result is a design trade. Either you design the commutator–brush system to operate in a semi-wetted environment and accept that fuel chemistry shapes the wear, or you isolate the motor and put more faith into seals that aging fuel will slowly attack.

Washer and coolant pumps

Washer pumps and small coolant pumps are usually intermittent, but water and glycol mix find ways into housings over time. Bilge-style pump repairs in hobby forums give a crude but honest picture: seized shafts from corrosion, brushes that still have length but have lost contact quality, commutators with a patch of heavy rust or green copper salts near a housing crack.

In these roles, the commutator design has to assume occasional contamination. Wider bars, robust slot undercuts, and brush grades that tolerate a dirty environment are worth more than a minimal reduction in electrical noise. Cleaning and self-polishing behaviour matter more than perfect efficiency.

Long idle periods also hurt. A pump may sit unused for months, then run flat-out for a few seconds in freezing weather. Any film instability, corrosion, or condensation on the commutator is then punished in a single high-current start. The first start after long storage is often the harshest contact event of the motor’s life.

One motor family, three different design briefs

You can see the differences by laying the three side by side. Numbers vary by supplier, but the design directions are consistent.

| Application | Duty style | Typical pain points for the commutator | Design bias in the commutator and brushes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Window lift | Very intermittent, frequent near-stall use, bidirectional | Localized bar burning at stall positions, arcing at starts in cold or wet doors, NVH from brush noise into door panel | Moderate bar count, small diameter, geometry tuned for both directions, brush grades aimed at stable film under high peak current and humidity |

| HVAC blower / cooling fan | Long operating hours, moderate load, usually one direction | Slow uniform wear, tonal noise if geometry or balance is off, thermal aging of hub and insulation | Higher bar count, good roundness and balance, brush force set for low noise and long life, materials chosen for steady medium temperature |

| Small pumps (washer, some coolant, some fuel) | Short bursts or continuous depending on role, fluid nearby or in contact | Corrosion or contamination on segments, accelerated wear when wetted by aggressive fuels or dirty water, issues after long idle periods | Segments and undercuts tolerant of dirt, chemistry-compatible plastics and resins, brush grades that keep contact under fluid or moisture exposure, sometimes sealed motor to keep commutator dry |

The underlying physics is the same. The commutator just answers three different briefs.

Material and geometry choices that rarely show up in datasheets

Suppliers talk about copper and insulation materials in marketing language, but their internal design notes are more practical. Recent overviews of commutator structure describe the combination of copper segments, insulating materials, and plastic shells as a balancing act between safety, current conduction, mechanical strength, and weight.

A few decisions matter a lot for automotive actuators, even when they are not spelled out.

Segment material and plating. High-purity copper is standard, but additives or surface treatments can change how the running film forms with a given brush and environment. In door modules, for example, a surface that forms a robust film despite moisture and small voltage cycling is worth more than a tiny conductivity gain that only helps at full load.

Plastic hub system. The hub has to handle press-fit stress from the shaft, centrifugal forces from high-speed operation, and thermal cycling from cabin to heat-soaked vehicle interior. Automotive commutators must also tolerate chemical exposure from outgassing plastics, door cavity vapours, and occasionally fuel or washer fluid. The hub is not just a carrier; if it creeps or cracks, segment alignment and insulation gaps change over time.

Insulation between segments. Papers on failure analysis of commutators often mention degraded mica or resin between segments that has become conductive or physically broken. In a pump motor, this can be accelerated by moisture and contaminants; in blowers, by thermal cycling. The result is bar-to-bar leakage that increases noise and lowers efficiency long before the motor actually stops working.

Brush arrangement and spring system. The commutating plane is a familiar concept; practical engineers also worry about how the springs age, whether brush holders clog with dust, and whether brush movement under vibration leads to intermittent acceleration of wear. The same commutator can perform well or poorly depending on whether springs keep the brush on the segment with consistent pressure over the actual life profile of the car, not just in lab tests.

What failures on the bench reveal about life in the car

Experienced repair technicians and motor engineers tend to look at commutators as storybooks. Technical articles on carbon brushes describe typical surface conditions — uniform brown film, streaking, grooving, bar burning — and tie them to specific underlying issues.

For the three applications here, patterns repeat.

Window lift motors often show localized black or blue bars corresponding to stall positions, combined with overall acceptable brush length. There may be a slight eccentric wear pattern if the motor has seen water ingress and corrosion at the bearings. Customers report slow or noisy windows, not complete failure.

Blower motors show even, slightly roughened copper with a uniform film, but brushes worn to near the end of travel. Noise complaints tend to come just before electrical failure, as the worn brush becomes mechanically unstable and chatter increases.

Pumps are more varied. Washer pumps sometimes come in with commutators that have normal wear but shafts that have seized or seals that have leaked. Fuel pumps may show surprising brush wear relative to age if fuel quality is poor. Instances of commutator segments with spot corrosion or green deposits often reveal that water has made its way into housings that were never meant to see it, either through cracked plastics or aged seals.

Looking at these patterns early in a vehicle program, on accelerated tests rather than customer returns, lets the design team adjust brush grade, spring force, or commutator finish before the damage is baked into warranty statistics.

Design habits that age well

Assuming you already know your brush chart, current density limits, and basic thermal modelling, most of the useful habits around commutators in these small automotive roles are about observation and boundary thinking.

On window lifts, treat worst-case stalls and low-temperature starts as first-class design cases, not rare abuse. If test benches show consistent bar burning in specific positions, look at both software (current limits, pinch algorithms) and the mechanical alignment that might stop the glass always in the same rotor orientation.

On blowers and fans, track not just power and efficiency, but how the acoustic spectrum shifts with age. A commutator that starts quiet but develops tones as brushes wear is telling you about roundness, bar height variation, and possibly a mismatch in thermal expansion between hub and copper.

On pumps, especially where fluids can reach the commutator, tie your design decisions to real fuel and fluid chemistry, not idealized samples. Field reports about brush wear or corrosion in particular fuels usually trace back to decisions about submergibility, sealing, and material compatibility that were made early and then forgotten.

None of this is glamorous work. It is laboratory time, door tear-downs, and patient cross-checking of endurance parts. Yet for a few grams of copper and carbon per motor, it shapes how reliable, quiet, and predictable those everyday automotive functions feel over a decade.

And in a car full of electronics, that small mechanical switch on the rotor still carries a lot of responsibility.