Commutator Wear: A Deep, Practical Guide

If you work around DC motors, generators, or exciters long enough, you eventually meet that commutator: streaked, grooved, sparking, and making everyone quietly nervous.

This guide is written the way an experienced maintenance engineer would explain it on the shop floor — not like a datasheet. We’ll connect what you see on the surface to what’s actually happening electrically and mechanically inside the machine, and then to what you can do about it.

Table of Contents

1. What Is Commutator Wear, Really?

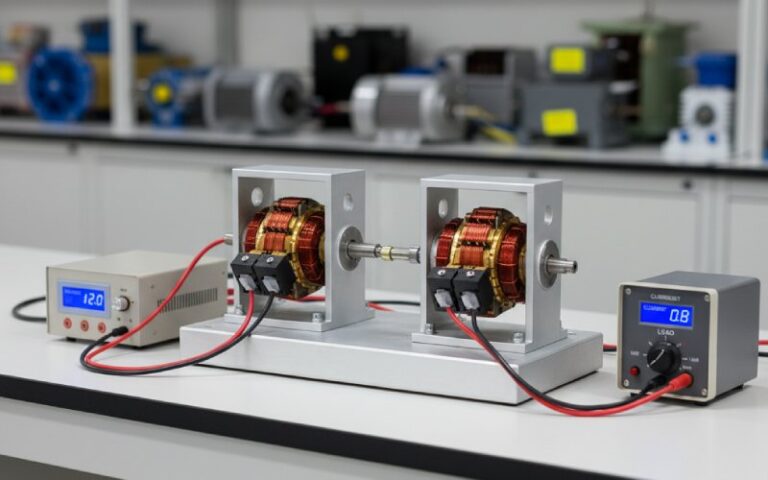

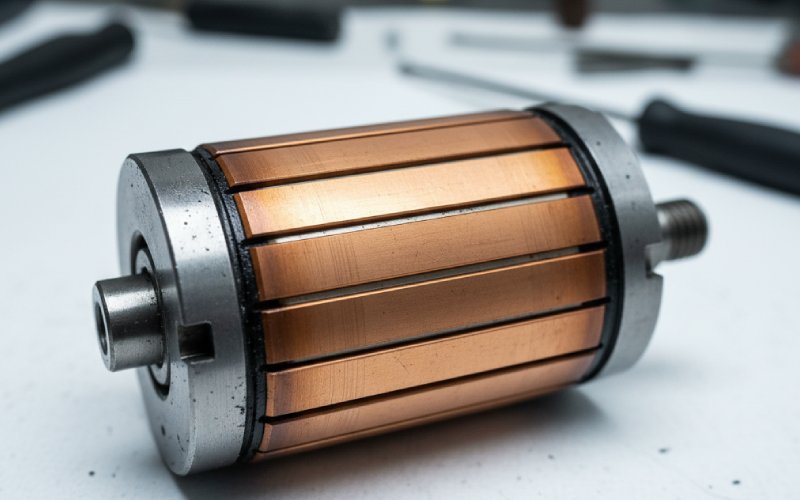

A commutator is the rotating copper cylinder made of many insulated bars that the brushes ride on. It’s the sliding interface that turns the messy AC in the armature winding into usable DC at the terminals.

Every second the machine runs, the brush–commutator interface is:

- Conducting current

- Generating heat

- Physically rubbing

So some wear is normal and expected. Modern guides explicitly treat commutator life as a consumable, not a “perfect forever” item — the real goal is predictable, controlled wear rather than zero wear.

Where things go wrong is when that wear becomes uneven, accelerated, or unstable. That’s when you get grooving, burning, copper drag, heavy streaking, and the sort of arcing that makes people reach for the emergency stop.

2. Three Big Mechanisms Behind Commutator Wear

Most commutator problems are some mix of these three:

- Mechanical wear – simple abrasion from brushes, dust, or misalignment.

- Electrical wear – micro-arcs during commutation eroding the copper bars.

- Chemical / environmental wear – contamination, humidity, corrosive gases attacking film and copper.

Think of the commutator like a race track and the brushes like racing tires. If:

- The track is rough or out-of-round → the tires get chewed up.

- The cars slam the throttle on and off (load swings) → rubber strips, hot spots.

- The weather is awful (dust, moisture, corrosive atmosphere) → everything degrades faster.

Same story on your machine.

Common accelerators of wear:

- High current density and overloads

- Incorrect brush grade

- Too little / too much brush spring pressure

- Vibration and poor shaft alignment

- Dirty, dusty, or corrosive environment

- Poor commutator geometry (out-of-round, high bars, raised mica)

3. Reading the Surface: What Different Wear Patterns Are Telling You

If you only remember one mental model, use this:

The commutator surface is a logbook. Each pattern is a message about load, brushes, springs, environment, and alignment.

Below is a condensed “field table” you can print or adapt.

3.1 Quick Wear Pattern Cheat Sheet

| Wear pattern | What you see on bars | Likely causes (primary) | Risk level* | First actions to consider |

| Normal film | Smooth, continuous tan–brown film, light polish | Stable load, proper brush grade & pressure | Low | Keep inspecting; don’t “fix” what’s healthy |

| Grooving | Uniform circumferential grooves under brush width | Abrasive dust, overly abrasive brush, too-light spring pressure | Medium | Clean machine, review brush grade, check/adjust spring pressure |

| Copper drag | Copper smeared across slots, often at trailing bar edges | Overheating, softening of copper, vibration, abrasive brush | High | Reduce load/temperature, increase spring pressure, re-chamfer |

| Bar-edge burning | Dark, burned edges on bars, sometimes etched trailing edges | Poor commutation; wrong brush grade, neutral mis-set, wrong interpole strength | High | Check brush grade, reset neutral, verify interpole and load |

| Slot/bar marking | Alternating dark/light bars in a pattern linked to slots | Faults in armature winding or uneven current distribution | High | Electrical tests on armature, consult repair shop |

| Threading / streaking | Fine lines or streaks around surface, metal transfer | Excessive arcing, contamination, poor brush-film stability | Medium–High | Investigate contamination, brush grade, spring pressure |

| Pitting / frosting | Tiny pits or dull “frosted” look | Arcing, high current density, commutation instability | Medium | Check load profile, brushes, springs, interpoles |

Risk level assumes pattern is *developing, not fully catastrophic. In practice, risk escalates fast when arcing and heating are visible.

3.2 Patterns That Are Not a Big Deal (Yet)

One thing the better commutator guides stress: not every imperfect surface is a failure. Many healthy machines run with surfaces that are mottled, streaked lightly, or film-heavy but stable.

As long as you have:

- Smooth brush contact

- No visible sparking beyond a faint, even glow

- No rapid brush wear

- No abnormal noise or vibration

…you may be looking at a perfectly acceptable commutator, even if it doesn’t match the “textbook chocolate-brown” picture.

4. Root Causes: Going Deeper Than “Bad Brushes”

It’s easy to blame problems on brushes — they’re visible and easy to swap. But commutator wear is usually systemic, involving several factors interacting over time.

4.1 Brush Grade and Current Density

Different carbon brush grades are optimized for:

- Commutation ability (how well they handle current reversal)

- Mechanical hardness / abrasiveness

- Film-forming behavior

- Operating temperature range

Mis-matched brush grade often shows up as:

- Grooving (brush too abrasive for your copper & environment)

- Heavy streaking or threading (poor film + metal transfer)

- Rapid brush wear even with a “nice” commutator

4.2 Brush Spring Pressure

Brush pressure is one of the most powerful — and most abused — parameters.

Too low:

- Poor contact, higher contact resistance

- More arcing during commutation

- Threading, grooving, pitting, and accelerated wear on both brush and commutator

Too high:

- Excessive mechanical wear (like driving with the brakes slightly on)

- Overheating and copper drag as the surface runs hotter

4.3 Geometry & Mechanics

The best carbon and springs can’t save:

- Out-of-round commutator (runout)

- High bars or insufficiently undercut mica

- Loose bars/segments causing brush bounce

- Poor shaft alignment or worn bearings causing vibration

These show up as:

- Uneven wear around the circumference

- Brushes chattering or bouncing

- Localized burning where the brush loses and regains contact

4.4 Environment & Operation

Real plants are dusty, hot, and imperfect. That matters.

Things that quietly trash commutators over months:

- Cement, carbon, metal, or wood dust

- Moisture + corrosive fumes (chemicals, combustion products)

- Frequent starts/stops and deep load cycling

- Poor ventilation or clogged filters

5. A Practical Inspection Workflow (You Can Actually Follow)

Let’s turn all of this into a repeatable on-site routine.

5.1 Before You Shut the Machine Down

While it’s still running, note:

- Brush sparking level

- Unusual sounds (brush chatter, humming, rattling)

- Smell (burning insulation, ozone, burnt copper)

- Temperature at bearing housings and commutator end (non-contact thermometer if possible)

These symptoms often disappear when the motor stops — so grab them early.

5.2 Visual Inspection After Shutdown

Once locked out and safe:

- Look at the commutator surface

- Is it smooth or ridged?

- Color uniform or patchy?

- Any obvious bar-edge burning or copper dragged across slots?

- Check brushes

- Even wear across all brushes?

- Glazed, chipped, or cracked?

- Length above minimum recommended?

- Brush holders & springs

- Spring movement free and not binding

- Brush moves freely in holder

- Contact face still aligned with commutator tangent

5.3 Measurements That Add Real Value

If you have the tools, periodically track:

- Commutator diameter and runout

- Brush spring force (or at least setting/angle)

- Insulation (megger) and bar-to-bar tests if slot/bar marking is suspected

- Bearing condition and shaft alignment

Logging these over months gives you a trend — and trends are gold for predicting when to schedule a resurfacing instead of waiting for a failure.

6. Preventing Commutator Wear: Strategy, Not Panic

When you look at high-performing maintenance programs (power plants, big industrial DC drives, etc.), commutator wear is managed, not reacted to. Their playbook tends to have the same pillars.

6.1 Keep the Surface Healthy

- Maintain a smooth, round commutator within tight runout tolerance; industry references commonly call for a few thousandths of an inch or better for proper brush contact.

- Use fine abrasives / stones correctly for light resurfacing — never random sandpaper unless you really know what you’re doing and follow brush makers’ recommendations.

- Ensure mica undercut is appropriate so brushes ride the copper, not the insulation.

6.2 Choose and Maintain the Right Brushes

- Work with reputable brush suppliers who can match grade to duty (load profile, environment, speed).

- Standard practice is to inspect brushes every few hundred to ~1000 hours depending on duty and environment, replacing before minimum length.

- Re-seat new brushes properly so they make full-area contact from the start and don’t create hot spots.

6.3 Control the Environment

- Seal or filter where possible; filter and clean forced-ventilated motors so abrasive dust doesn’t sandblast the copper.

- Keep oil, grease, and moisture out of the brush/commutator zone.

- For particularly harsh atmospheres, consider coatings or special brush/film systems designed to improve wear and reduce sparking.

6.4 Run the Motor the Way It Was Designed

- Avoid chronic overloads and underloads (both can lead to poor commutation and weird film conditions).

- Don’t ignore violent torque reversals, frequent starts, or big step loads — they hammer the commutator as well as the mechanical system.

- If you upgrade drives or change duty cycles, revisit brush grade and settings; they were chosen for a particular operating profile originally.

7. Resurface, Re-true, or Replace? Making the Call

This is where many teams either over-react (“change everything!”) or under-react (“we’ll baby it along another year”).

7.1 When Wear Is “Acceptable but Watch”

You can usually keep running (with more frequent inspections) when:

- Surface is smooth to the touch

- Film is non-uniform but stable

- No destructive sparking, just mild “brush glow”

- Brushes are wearing at a predictable, reasonable rate

The more modern literature emphasizes that many commutators in service look a little ugly but run just fine; the key word is stable.

7.2 When to Plan a Resurfacing / Undercutting

Schedule controlled work if you see:

- Persistent grooving or threading that cleaning and minor adjustments don’t stop

- Copper drag starting to bridge slots

- Mild bar-edge burning but no deep damage yet

- Out-of-round beyond your maintenance threshold, or trending worse

In-shop or in-place machining plus undercutting, followed by proper brush seating, can add years to commutator life if done carefully.

7.3 When Replacement or Major Rewind Is the Adult Answer

Don’t keep gambling when:

- Bars are loose or mechanically damaged

- Deep burning, severe pitting, or metal loss on many bars

- Recurrent heavy arcing despite corrected settings, good brushes, and clean environment

- Armature electrical tests confirm serious winding problems along with surface damage

At that point, replacement or a professional rebuild is usually cheaper than repeated unplanned outages.

8. Simple Checklists You Can Use Tomorrow

8.1 Routine Inspection Checklist

- Look at commutator surface (color, smoothness, visible patterns)

- Check brush length, seating, and lead condition

- Verify brush springs aren’t binding and have reasonable travel

- Vacuum out dust (don’t just blow it deeper into the machine)

- Listen for brush noise while running

- Log observations, even if “normal” — future you will thank you

8.2 After You See a New Wear Pattern

- Compare what you see with a wear pattern chart or your own table.

- Ask: Did anything change? (load, environment, brush grade, drive settings, maintenance work, season)

- Check brush grade vs. application with your supplier

- Measure what you can (runout, spring force, temperatures, vibration)

- Decide: monitor, adjust, resurface, or plan a bigger repair

8.3 “If You Only Remember Three Things…”

- The commutator is supposed to wear — the real enemy is uncontrolled wear.

- Most scary-looking surfaces are telling a story about brushes, springs, load, and environment, not just “bad copper.”

- A simple, consistent inspection routine will catch problems early enough that you can fix them on your schedule, not the machine’s.