Difference Between Commutator And Rectifier

Both commutator and rectifier force current into one preferred direction, but they live in different layers of a system. A commutator is part of the rotating machine itself, synchronised with its mechanical angle, while a rectifier is a separate conversion stage that sits in the power path and processes whatever AC you feed it. They sometimes overlap in function; they almost never overlap in how you design around them.

Table of Contents

A quick mental model

Start with this: every conventional DC generator armature produces an internally alternating voltage. The commutator is a rotary switch that keeps reconnecting coils to the brushes so that, viewed from the terminals, the output looks one-directional. In that sense it behaves as a mechanical rectifier, built into the rotor, timed by the shaft.

A rectifier, on the other hand, is any device or circuit that takes an AC input and yields a DC output, usually by using elements that naturally prefer one current direction: diodes, thyristors, transistor bridges, and so on.

So both “straighten” current. One does it by moving copper segments under stationary brushes. The other does it with static junctions and control pulses.

What each one actually is

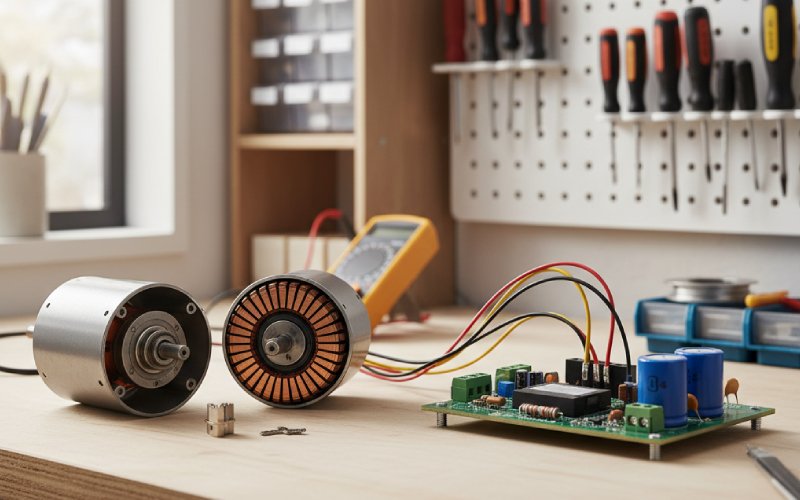

The commutator is a segmented cylinder mounted on the rotor shaft, with each segment wired to part of the armature winding. Stationary brushes press on this cylinder, picking up or feeding current. As the rotor turns, successive segments meet the brushes, which flips which coil is connected to which terminal. That periodic reversal, locked to the mechanical position, keeps torque in a DC motor roughly unidirectional and the external current in a DC generator roughly one-directional.

The rectifier is not tied to shaft position at all. It’s just a circuit: maybe a single diode for half-wave, maybe a bridge using four diodes for full-wave, maybe a six-pulse or twelve-pulse thyristor bridge in an HVDC station. Its switching is electrical, not mechanical, determined by the AC waveform and the device characteristics or the firing pulses.

So a commutator literally rides on the rotor. A rectifier just sits wherever layout and thermal design say it should.

Side-by-side comparison

Here is the high-level comparison most glossed-over explanations skip.

| Aspect | Commutator | Rectifier |

|---|---|---|

| Physical nature | Rotary electromechanical switch: copper segments on the shaft plus carbon (or similar) brushes. | Static circuit using diodes, thyristors, transistors, or similar one-way devices. |

| Where it lives | Integrated into the rotor of DC motors and generators (and universal motors). | Separate stage in the power path: board-level bridge, module, or converter bay. |

| Primary job | Periodically reverses connections between armature coils and external circuit so external current stays one-directional and torque direction stays useful. Acts as a mechanical rectifier inside DC machines. | Converts AC at its input terminals into DC at its output terminals by blocking one polarity or steering it, often feeding a filter or DC bus. |

| What it “sees” | Internal armature EMF in a machine, tightly coupled to rotor position and field. | Line or transformer secondary voltage, often with no knowledge of the mechanical system. |

| Control mechanism | Commutation instant is fixed by geometry: brush position, number of segments, and shaft angle. Fine-tuning via brush shift, interpoles, etc. | Control (if any) is electronic: gate pulses in thyristor/IGBT rectifiers, modulation strategies, digital controllers. |

| Waveform shaping options | Limited. You can improve commutation, but the basic ripple pattern follows the number of poles/commutator segments. | Extremely flexible with modern active rectifiers: can shape current, power factor, harmonics, bidirectional flow. |

| Losses and stress | Brush drop, friction, copper segment resistance, arcing. Thermal and mechanical wear live in the same place. | Mainly conduction and switching loss in semiconductors, plus magnetic and filter losses; no sliding contacts. |

| Reliability and maintenance | Brushes and commutator surface wear; need inspection, cleaning, resurfacing in larger machines. Sparking can be a problem in dusty or explosive atmospheres. | Often treated as maintenance-free until failure; lifetime dominated by temperature cycles, over-voltage events, and insulation aging. |

| Power scale | Practical up to moderate power; very large DC machines are rare because commutation becomes difficult and risky. | Scales from milliwatt phone chargers to gigawatt-class HVDC converter stations using line-commutated or voltage-sourced converters. |

| Typical modern use | Small/medium DC motors, universal motors in tools and appliances, some legacy traction drives. | AC-to-DC supplies, DC links, HVDC transmission, motor drives, chargers, almost anywhere you see “AC in, DC bus out”. |

The table hides one silent point: one of them is gradually disappearing from new designs. Not the rectifier.

“Isn’t a commutator just a rectifier?”

Inside a classical DC generator, yes, in a strict functional sense. The armature winding produces an internally alternating voltage; the commutator reverses connections so that the voltage at the brushes does not reverse, giving a unidirectional output. That is rectification by mechanical switching.

But that definition is too narrow for how engineers use the words day to day.

When people say “rectifier” now, they usually mean a standalone AC-DC converter block, often built from semiconductors, possibly with control and power-factor correction. It is not constrained by rotor geometry. It can be redesigned or swapped without touching the machine shaft. It can run bidirectional in a regenerative drive.

When people say “commutator”, they usually mean a specific mechanical structure on a DC or universal motor/generator that has to survive wear, arcing, and misalignment, and that is deeply entangled with field design, armature winding layout, and torque ripple. The fact that it also happens to rectify is almost incidental compared with its role in keeping torque and current direction aligned with the field.

So, yes: every DC machine commutator is implementing rectification. No: in modern power-electronics language, it is not what we call a “rectifier”.

Design perspective: where each still makes sense

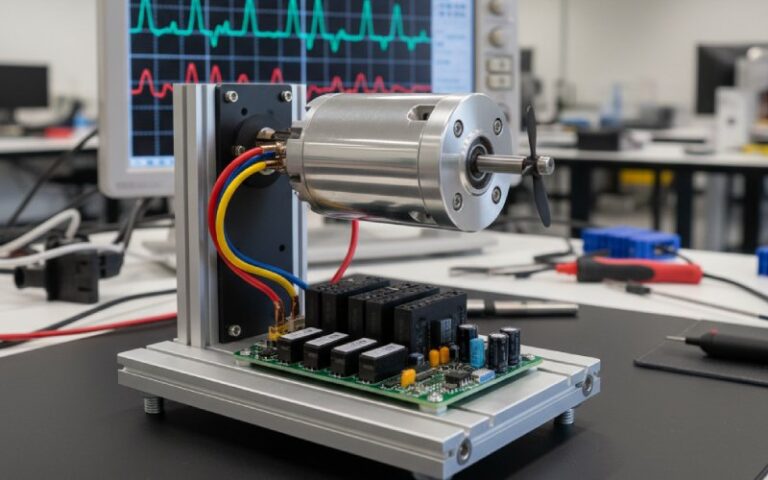

If you are designing anything fed from the mains or from a high-frequency transformer, you reach for a semiconductor rectifier. Bridge modules are cheap, compact, and efficient, and they scale from tiny wall-warts to large front-ends in industrial drives. At transmission levels, thyristor and VSC converters dominate any serious DC link, because sliding contacts and commutator arcs have no place at those voltages and powers.

The commutator survives in a narrower set of niches. Hand tools, vacuum cleaners, some small appliance motors: the classic universal motor still gives a good power-to-weight ratio at low cost, and mass-manufactured commutators are acceptable there. In automotive starters and some legacy traction systems, commutators remain because the platform was built around them. But whenever designers can afford electronics, brushless DC machines with electronic commutation plus semiconductor rectifiers usually win on efficiency, noise, and lifetime.

There are also hybrid ideas in research, where mechanical rectifiers using commutator-like structures are combined with triboelectric or other novel generators. Even there, the line between “commutator” and “rectifier” is more about implementation than about what the current waveform looks like.

Control, commutation, and waveforms

The commutator’s timing is set in copper and carbon. Change the brush position or add interpoles and you adjust commutation overlap, spark behaviour, and torque ripple, but you are still riding the mechanical cycle. The waveform quality depends on pole count, number of commutator segments, and load current. Fixing a commutation problem usually involves grinding, cleaning, and maybe rewinding.

Rectifiers, especially controlled ones, are more malleable. A six-pulse thyristor bridge in an HVDC scheme adjusts its firing angle to control DC voltage and power flow, and a VSC front-end can shape its current almost arbitrarily within device ratings. Harmonics, power factor, and dynamic response become firmware questions as much as hardware questions.

That difference matters when you are debugging a system. Mechanical commutation faults tend to show up as arcing, brush wear, commutator bar discoloration, local heating. Rectifier issues often show up as abnormal waveforms, high device temperature, nuisance trips, or acoustic noise from magnetics. Same goal, different failure language.

How this changes your mental wiring diagram

Thinking of the commutator as “part of the machine” and the rectifier as “part of the conversion chain” keeps design decisions cleaner.

If your problem statement is “I have AC and I need a DC bus”, you are in rectifier territory. Topology choice, conduction losses, filters, EMI, and control algorithms are the real work.

If your problem statement is “I have a brushed DC or universal machine and I care about torque, life, or maintenance”, you are in commutator territory. Brush grade, spring pressure, surface finish, commutating poles, and the subtle dance between field distortion and brush position start to matter.

Both objects enforce one-way behaviour in current. One does it by spinning copper under graphite. The other does it by embedding physics of PN junctions and gate-controlled switches into a static block. Treating them as the same thing hides most of what makes real designs succeed or fail.