Commutator Motors vs. Induction Motors in Industrial Applications

If you are choosing for a new industrial drive today, the safe default is a three-phase induction motor with a modern drive. Commutator machines still matter, but mainly in legacy heavy drives and a few speed-critical niches. Most plants spend their capital migrating away from brushes, not adding more of them. That is the direction the market and the maintenance data both point to.

Table of Contents

Quick verdict before the long story

In industrial environments, induction motors became the standard because they are structurally simple, cheap to build in volume, tolerant of abuse, and need very little attention beyond bearings and the cooling path.

Commutator motors bought their place in history with high starting torque, wide speed range, and precise torque control long before high-power electronic drives were routine. DC commutator drives ran rolling mills, paper machines, and serious machine tools for decades for exactly that reason.

Once vector-controlled induction drives and permanent-magnet machines became practical and cheap, that advantage narrowed. For most new plants, the numbers no longer defend a commutator unless you are solving a narrow, well-defined problem or nursing existing assets.

What “commutator motor” means here

The phrase gets used loosely, so it helps to state the scope and move on.

Industrial engineers usually touch three broad families with commutators. First, classic DC motors with mechanical commutation: shunt, series, compound, and permanent-magnet DC drives. These powered steel mills, paper lines, winding machines, and early robots because field and armature control give almost linear speed–torque behavior.

Second, AC commutator machines such as universal motors, repulsion motors, and older repulsion-induction types. These are common in small high-speed devices and portable tools where you want aggressive torque and compact size but accept higher noise, shorter life, and worse efficiency.

Third, more esoteric AC commutator machines like the Schrage motor: effectively a wound-rotor induction machine plus built-in frequency converter, using brush position to control speed and power factor. It was a clever variable-speed solution for textile, carpet, and similar drives before solid-state inverters took over.

On the other side of the comparison sit single- and three-phase induction motors. In industry you are mostly looking at three-phase, squirrel-cage units. They are now the dominant motor type on factory floors worldwide.

Core trade-offs that actually change your plant

Torque, speed range, and dynamic behavior

If you draw torque–speed curves for the main players, the reason DC commutator drives were loved in steel and paper lines is obvious. With armature-voltage and field-weakening control, DC motors give a wide constant-torque region and a wide constant-power region, with a fairly straight relationship between commanded voltage and shaft speed. That makes tension control, coordinated line speed, and four-quadrant operation almost routine.

Universal motors and similar AC commutator types go to the other extreme. High starting torque, high base speed, and mechanical limits rather than electrical limits tend to cap speed. They tolerate frequent start–stop cycles and can be driven quite hard, which is why they end up in compact tools and appliances.

Induction motors with fixed frequency are more restrained. Without a drive, your speed window is narrow around synchronous speed, with slip giving some compliance but not a wide continuous range. Large induction machines can give decent starting torque when designed for it, but for demanding starts and frequent reversals they need help from drives, rotor resistance (older wound-rotor designs), or soft-starting methods.

Modern vector-controlled induction drives changed that picture. They emulate the current control and decoupled torque/flux behavior that DC commutator drives provided, giving fast torque response and a broad speed range using standard squirrel-cage motors. From the control engineer’s seat, an induction machine now feels a lot like the older DC option, especially in the constant-torque region.

So on torque and speed behavior, commutator motors still look good, but drives narrowed the gap so much that the mechanical complexity penalty starts to dominate.

Control stack and power electronics

Historically, DC commutator drives were attractive because rectifiers and chopper controls were cheaper and easier to scale than high-power variable-frequency inverters. The plant could keep a simple AC supply and put most of the sophistication in a DC drive panel.

That argument has decayed. Commodity IGBT and now SiC-based inverters, plus mature field-oriented control schemes, make AC drives straightforward to specify and buy. A typical three-phase induction motor plus a standard VFD is now the baseline catalog pairing for constant-speed and variable-speed loads alike.

AC commutator machines such as Schrage motors tried to address variable speed before electronics by building the “converter” into the rotor and commutator itself, adjusting injected EMF with brush position. That solution is intellectually neat but mechanically delicate. It gave smooth speed variation and power-factor correction, but with more copper, more carbon, and more things to align. Modern plants prefer solid-state gear in cabinets over sliding contacts inside the rotor.

For new projects, control simplicity now favors induction machines: standard motors, standard drives, standard diagnostic tooling. Commutator motors now appear mostly where existing drives and control cabinets are already in place and the business case for full conversion is weak.

Reliability and maintenance reality

The structural difference is blunt. Induction motors have no brushes and no commutator; the rotor is either a squirrel cage or a wound rotor with slip rings only in special cases. Fewer mechanical contact points mean fewer wear surfaces. That translates directly into lower maintenance and longer continuous operating intervals.

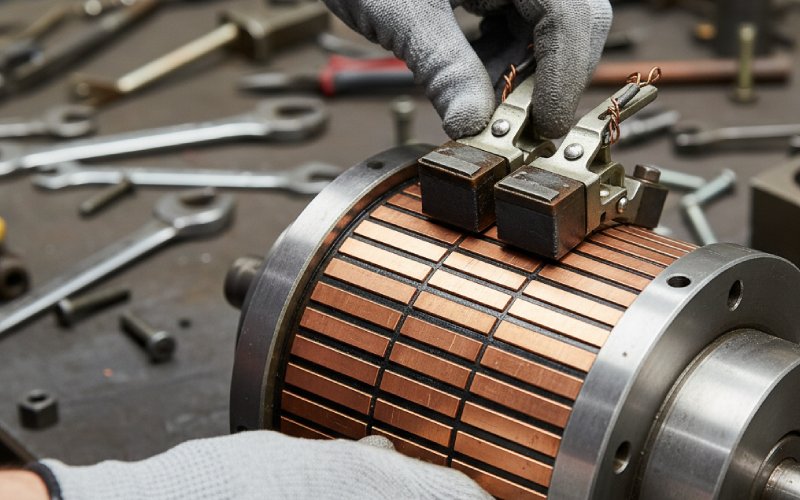

Commutator motors trade this simplicity for performance. Brushes wear. Commutator segments need cleaning, dressing, or machining. You get carbon dust, mechanical noise, and a finite brush life that must be scheduled into your shutdown windows. Universal motors add higher acoustic noise and vibration on top, which is tolerable in portable tools but less acceptable near operators for long shifts.

In a steel mill or paper machine with large DC commutator drives, these maintenance tasks are accepted as part of owning the asset. Many such sites have strong in-house skills for brush gear and commutator work. That softens the blow, but it does not remove it. Each unplanned outage from brush failure is still expensive.

When reliability and uptime are weighted heavily, and when you have multiple similar motors across a plant, induction machines gain a strong statistical advantage just by having fewer moving electro-mechanical interfaces.

Efficiency and lifetime energy cost

Bare induction motors are already efficient, especially in their rated operating region. Premium-efficiency and super-premium designs push that further, and regulatory pressure keeps that trend going.

Commutator motors incur extra copper losses and contact losses at the brushes. Universal motors in particular waste a noticeable portion of input power as heat and noise; that is tolerated in small intermittent-duty machines but scales poorly for continuous industrial duty.

With a drive in the loop, the comparison shifts to system efficiency. An induction motor plus modern VFD can maintain good efficiency across a broad speed range, although switching and filtering losses appear. DC commutator systems with older SCR or chopper controls may look less favorable once you include drive losses, field losses, and increased cooling requirements.

On a long-life industrial asset running many hours per year, a few percentage points in system efficiency make a very clear difference in total cost of ownership. This is one of the quiet reasons many plants are willing to absorb mechanical and electrical retrofit work to move from DC commutator to AC induction or PM synchronous drives.

Safety, environment, and compliance

Brushes mean sparking and carbon dust. For dusty, flammable, or strictly clean areas this is not just inconvenient, it can be disqualifying. Hazardous-area drives based on low-slip induction machines with suitable enclosures and certified protection methods are now the standard pattern.

Noise is another practical concern. Universal and many other commutator motors produce higher mechanical and electromagnetic noise than comparable induction machines. That is acceptable for intermittent hand tools; it is a problem for continuous duty when you are trying to meet noise limits on a production floor.

From an EMC point of view, commutator arcing can inject broadband noise into nearby instrumentation. Modern VFDs are not innocent either, but with well-known mitigation practices (filters, cable design, grounding) they are easier to tame than uncontrolled brush noise inside a shared enclosure.

Side-by-side summary

To keep the discussion concrete, the table below compresses the comparison for the three main families most industrial engineers actually see.

| Aspect | DC commutator motor (industrial drives) | AC commutator motor (universal / Schrage) | Induction motor (3-phase industrial) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical power range and physical scale | From small actuators to very large mill drives; often sizeable frame, heavy rotor | Mostly small to medium power; compact form factors, especially universal motors | From fractional kW to multi-MW; broad range of standardized frames |

| Speed control behavior | Wide and smooth speed range via armature voltage and field; four-quadrant control is mature | Universal: wide speed range, but crude control and strong load-dependent behavior; Schrage: smooth mechanical speed variation via brush shift | Fixed frequency: narrow natural speed window; with VFD and vector control, wide programmable range with DC-like behavior |

| Starting torque and overload handling | High starting torque with straightforward control; good for heavy starts and frequent reversals | Very high starting torque in universal types; Schrage suitable for variable-speed heavy loads historically | Design-dependent; can give good starting torque, but heavy-duty starting often assumes a drive or specific design class |

| Efficiency in continuous duty | Reasonable but reduced by commutator and field losses; older generators/rectifiers may add losses | Often modest efficiency, especially universal motors; acceptable for intermittent duty | High efficiency at rated point; premium classes and optimized rotor designs push this further |

| Maintenance profile | Regular brush inspection and replacement; commutator cleaning or machining; more internal mechanical wear items | High brush wear and commutator maintenance for universal; Schrage adds extra mechanical complexity | Primarily bearings and cooling path; no brushes or commutator in squirrel-cage types, so lower routine maintenance |

| Environmental and safety fit | Brush arcing and dust limit use in hazardous or very clean areas; requires careful enclosure design | Similar or worse limits due to sparking, noise, and dust; mainly kept out of hazardous zones | Well suited to harsh and hazardous areas with appropriate enclosures; no internal sparking components in the rotor |

| Typical modern industrial roles | Legacy mill drives, large winding systems, some specialized machine tools where replacement cost is high | Small portable tools, some appliances, niche variable-speed drives in older plants | General industrial workhorse: pumps, fans, compressors, conveyors, mixers, cranes, and most automation axes with VFDs |

Where commutator motors still earn their space

If new induction drives are so attractive, why do commutator machines still matter at all in industrial discussions. Mostly because plants do not start as greenfield every time.

Large DC commutator drives in steel, paper, and similar process industries still exist in big numbers. The mechanical train and foundations around them were built for that exact machine. Replacing everything with induction or PM machines plus new drives can require major civil work, new cooling, and rewiring. Where the mechanical risk is high or downtime is expensive, operators sometimes prefer to keep the DC motor and modernize only the power electronics and controls.

There are also cases where extremely fast torque response and very fine low-speed behavior are required, and the engineering team is already fluent in DC drive control. A well-maintained DC commutator system can still perform well here, although the same level of performance is now achievable with AC servo or PM synchronous drives in many ranges.

On the AC side, universal motors and similar commutator types remain useful wherever you want aggressively compact, high-speed machines at relatively low cost and with intermittent duty cycles. Many plants accept these in hand tools, small benchtop devices, or auxiliary machinery where noise and maintenance are manageable and downtime cost is low.

Legacy Schrage and other AC commutator motors still sit on some older variable-speed drives. They are now specialty assets, often kept running until a major failure forces a decision either toward a full AC drive retrofit or toward retiring that production line.

Why induction motors became the default industrial choice

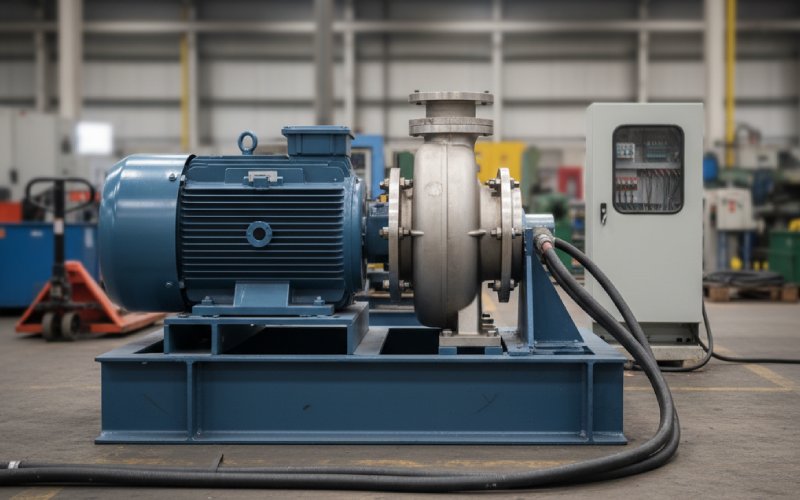

From the component view, a three-phase squirrel-cage induction rotor is hard to beat. It is a stack of laminations and bars, shorted at each end. No sliding electrical contacts, no commutator, and no field winding on the rotor. This geometry makes it durable and tolerant of electrical and mechanical abuse.

From the system view, these motors pair naturally with standard drives. Power utilities and regulations favor AC distribution. VFD manufacturers, enclosure vendors, and automation suppliers all build around the assumption that induction motors are the baseline. The result is an ecosystem that reduces engineering time and project risk if you follow the default pattern.

Modern industrial articles stress the same factors repeatedly: simplicity of construction, durability, low maintenance demands, and good efficiency, especially at or near rated load. Recent surveys describe induction motors as the backbone of industrial operations for exactly these reasons.

When you blend that with pressure on energy costs and decarbonization targets, the bias toward high-efficiency induction or PM synchronous machines grows even stronger. Commutator motors carry an inherent mechanical loss term and maintenance burden that eats into these goals.

Migration decisions: keeping or replacing commutator drives

For engineers working in existing plants, the real question is often not “which is theoretically better,” but “do we retire this commutator motor yet.”

Typical decision inputs are unromantic. How often do you replace brushes. How much outage time did you lose last year to commutator or brushgear faults. Can your local maintenance team still source quality brush material and service expertise. How hard would it be to change shaft height, base, and coupling if you moved to an induction or PM machine.

In many older DC drive installations, drive manufacturers now offer retrofit kits that retain the motor but replace aging thyristor gear and analog control with digital systems. That can give better diagnostics, better current limiting, and networked control without touching the mechanical core, buying you more years at lower risk.

At some point, though, the cost of planned overhauls, lost production from unexpected brush problems, and energy inefficiency crosses the cost of a full conversion to an induction or PM drive. When that crossover happens depends on local energy prices, product margins, and upcoming shutdown opportunities, not on any one technical variable.

Practical rules without pretending they are universal

If you were forced to pick using a blunt rule-set, it might look like this, keeping the caveat that every plant is messy.

For new industrial equipment, choose a three-phase induction motor with a standard VFD unless you have a clear, documented reason not to. The combination covers most speed, torque, and control requirements from pumps and fans to conveyors, mixers, extruders, and moderate-precision motion axes.

Use DC commutator motors when you are dealing with existing heavy drives whose mechanics and process integrations were built around DC behavior and where the downtime or civil work to convert is unacceptable for now. Work on improving drives, monitoring, and maintenance practice around them rather than replacing them in a hurry.

Keep AC commutator machines, especially universal motors, at the fringes of your industrial system unless you are solving a problem that genuinely benefits from their very high speed and torque density and can tolerate their noise and maintenance profile. Reserve them for tools and small machines where a failure is an inconvenience, not a plant-wide incident.

Closing thoughts

In everyday industrial engineering, the commutator versus induction question is less about theory and more about risk, downtime, and the competence your team already has in-house.

Induction motors, backed by modern drives, give a boring answer to most questions, and that is exactly what many plants want: a solution that keeps running with minimal care. Commutator motors still earn their keep when legacy assets or very specific performance needs justify the extra mechanical complexity. The job of the engineer is to know which situation they are actually in, not just which datasheet looks better.