Commutator Motors vs. BLDC Motors for Power Tools and DIY Equipment

If you mostly care about cordless tools, the short answer is: brushless DC (BLDC) usually wins on power-to-weight, runtime, control, and lifespan, and commutator motors usually win on sticker price and brutal simplicity. Corded gear and ultra-cheap tools still lean heavily on commutator designs; serious cordless and precision DIY projects lean the other way.

Table of Contents

What this comparison is really about

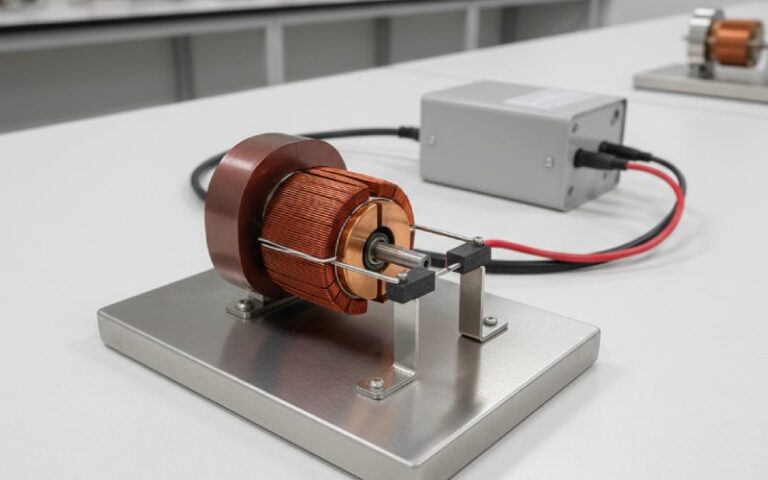

When I say “commutator motor” here, I mean the whole brushed family: traditional DC motors and the classic series-wound universal AC/DC motors that live in many corded drills, grinders, and saws. All of them switch current with brushes and a mechanical commutator. BLDC motors push that same job into electronics: permanent-magnet rotor, wound stator, and a controller that does the switching in silicon instead of carbon and copper.

Power-tool makers have already voted with their BOMs. Corded tools still use a lot of universal commutator motors because they’re compact, cheap, and happy on mains. Cordless tools, especially mid- to high-end, are rapidly standardizing on tri-phase BLDC drives paired with microcontrollers and lithium packs.

You already know how each topology works. So let’s stay with what matters in the shed, not in a motor textbook.

The practical verdict by tool category

For cordless drills, impact drivers, and compact saws, BLDC isn’t just a marketing sticker. Typical tri-phase BLDC setups in this size reach mid-80s to mid-90s percent efficiency under good design, while brushed power-tool motors live closer to roughly 60–80% and dump the rest as heat in brushes and copper. That efficiency gap turns directly into more holes per charge and less thermal throttling. It also allows brands to squeeze more torque into a smaller head, which is why modern brushless impact drivers look oddly compact compared with older brushed ones.

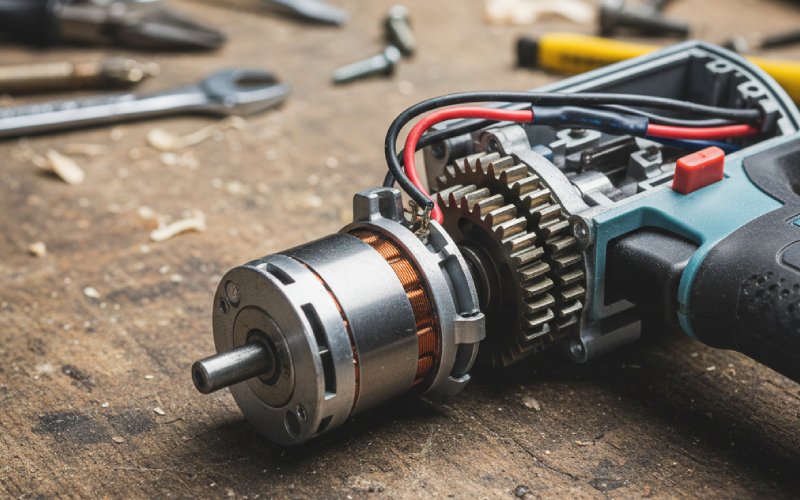

In low-cost corded drills, grinders, and jigsaws, universal commutator motors still make sense. You bypass the battery and the smart electronics, so total system cost is dominated by the motor and basic trigger circuit. A universal motor gives aggressive torque for its size, tolerates very high speed, and can happily chew itself toward retirement without a single line of firmware. The downside is noise, sparks, and relatively poor efficiency, which the wall socket hides as long as you don’t care about your power bill or neighbors.

Stationary workshop machines for hobbyists are in between. Many consumer-grade benchtop table saws or mitre saws still rely on universal motors for compactness. The sound signature and brush sparks are the tradeoff. If you value a quieter shop, cleaner EMI behaviour around CNC controllers, and less fine dust ignition risk, a BLDC retrofit or BLDC-based machine is more attractive, but you pay in controller complexity and cost.

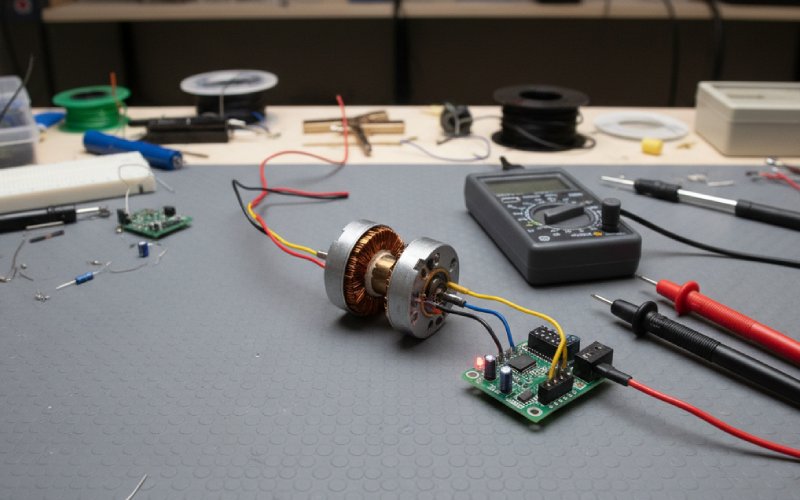

For robotics, CNC, and motion-controlled DIY equipment, BLDC or permanent-magnet synchronous servos are usually the grown-up choice. You already need precise positioning, current limiting, and torque control, so the controller you’d add to tame a commutator motor is halfway to a proper BLDC drive anyway. Brushed motors still work for quick jigs, prototypes, or where you expect abuse and don’t mind changing brushes.

For “garage special” battery builds—homemade e-carts, cordless shop vac conversions—your answer often follows parts availability. If you have a spare scooter BLDC and controller, use it. If you have a stack of old drill motors and no BLDC driver in sight, a commutator motor with careful gearing and fuses may be more practical, even if you know it’s not the elegant solution.

Numbers first: efficiency, lifespan, and cost

Here’s the kind of terse comparison engineers actually use when choosing a motor family. Values are approximate and assume power-tool-scale designs.

| Aspect | Commutator motor (brushed DC / universal) | BLDC motor |

|---|---|---|

| Typical efficiency under load | Often around 60–80% in this scale, with meaningful loss in brush friction and copper heating. | Commonly mid-80s or better with good tri-phase drives, with upper bounds reported near ~96% in optimised designs. |

| Control electronics | Can be run from simple switches or triac / basic PWM drives; closed-loop control is optional. | Requires active commutation logic, usually microcontroller-based, plus power stage and sensing; closed-loop control is built-in in most serious tools. |

| Typical lifespan | Limited mainly by brush and commutator wear; requires periodic maintenance in many designs. | No brush wear; life is dominated by bearings, insulation, and electronics. Usually longer runtime before any service. |

| Noise and EMI | Audible brush arcing, strong RF noise, and visible sparks; can be an issue around sensitive electronics or flammable dust. | Lower electrical noise, no brush sparks, easier to seal; better fit where EMI or stray sparks are unwelcome. |

| Initial cost | Motor itself is cheap and drive circuitry can be minimal; usually the lowest upfront cost. | Motor plus driver is more expensive; requires a controller IC or SoC plus power stage. |

| Operating cost over life | Higher due to lower efficiency, brush replacement, and more frequent failures. | Lower energy use and less maintenance give better total cost in high-duty or professional scenarios. |

| Integration in modern tools | Easy drop-in for simple triggers, less synergy with “smart” features. | Pairs naturally with battery management, protection, and smart features like stall detection and electronic clutches. |

If you strip away every buzzword, the table basically says: commutator motors are cheaper to build and simpler to drive, BLDC motors are better in almost every performance metric once you accept the electronics overhead.

How both motor types behave when abused

Real tools don’t live on test benches; they live in half-stalls, under cooling-starved shrouds, running off half-charged packs.

A commutator motor tolerates short periods of overload pretty well from an electrical standpoint. Stalling a universal motor slams a lot of current through the armature, limited mostly by its own resistance and whatever the cord or pack can provide. Windings and commutator heat up fast, but for brief events the worst you get is a shower of sparks, odor, and accelerated brush wear. The motor gives you a lot of warning before it dies.

A BLDC motor under the same mechanical abuse usually relies on its controller’s current-limit and thermal logic. The motor itself can handle high torque for short peaks, helped by good efficiency and often better thermal paths. But push it too far past what the controller expects and you don’t just cook copper; you can blow MOSFETs or trigger firmware faults. From the outside that can feel like “mysterious” shut-offs rather than a slow, noisy death.

In dusty woodworking or metal-grinding environments, the trade is more subtle. Commutator motors spray carbon dust internally and shoot ionising sparks at the commutator. That’s not ideal inside fine wood dust or volatile vapours, and it can contaminate bearings over time. BLDC motors, with no brushes and fully enclosed stators, reduce sparking and are easier to seal, which is one reason brushless units are attractive in sealed appliances and some hazardous applications.

Thermally, BLDC units have one additional constraint: permanent magnets dislike high temperature. Push them too hot for too long and demagnetisation creeps in. Brushed universal motors don’t have that exact weak point but instead risk insulation breakdown, commutator damage, and warped housings. Either way, poor airflow and continuous overload remain the enemy; BLDC just tends to give you more usable work for the same thermal budget.

Trigger feel, control, and safety functions

At the handle, BLDC tools feel different for structural reasons, not magic. The combination of microcontroller, current sensing, and tri-phase inverter lets designers shape torque and speed in software. Qorvo’s reference designs for cordless power tools, for example, show microcontrollers reading trigger position, battery voltage, motor current, and temperature, then driving the BLDC motor through a controlled commutation sequence.

That stack unlocks features that are now standard on pro-grade brushless tools: consistent speed under load, soft start, aggressive but controlled braking, stall detection, electronic clutches, and anti-kickback cut-offs when rotation spikes or stops too abruptly. The motor type is only half the story; the silicon behind it is the other half.

With commutator motors, you can approximate some of this, but the economics change. A simple triac or MOSFET PWM trigger gives basic speed control. Add current sensing and logic and you can implement overload cut-off, but now you’re partway toward a brushless-style control stack while still stapling it to a less efficient motor. For low-end tools, manufacturers usually stop at cheap analog control and rely on mechanical clutches and user judgement for the rest.

So when people say “brushless feels smarter,” it’s mostly because they are literally holding a small embedded system in the handle, not just a different motor topology.

Total cost: not just the motor price

On a spec sheet, BLDC hardware looks more expensive. Industry comparisons of motor families consistently show brushed motors at the bottom of the initial cost ladder, with BLDC at the top once you factor in the driver stage and sensing. That’s why the cheapest drills and grinders in a hardware aisle are almost always brushed.

Over a tool’s lifetime, though, operating cost reverses direction. BLDC motors waste less power as heat, so energy costs drop, and there are no brushes to replace. Several vendors now explicitly position BLDC as the lower total-cost choice where duty cycle is high, because maintenance and downtime matter more than saving a few dollars on day one.

For a DIY user who runs a cordless drill a few minutes per weekend, the math changes again. Electricity cost is almost noise compared with the tool price. In that case, the argument for BLDC shifts away from “you’ll pay it back in energy savings” toward “you’ll get a smaller head, better low-speed torque, and a motor that is unlikely to wear out before the chuck or gearbox.” The financial payoff is softer, but the user experience still shifts in favour of brushless.

Professional trades, on the other hand, push tools hard all day. There, the longer brushless life, higher efficiency, and integrated safety features align nicely with the economics: a tool that fails mid-job is more expensive than one that cost a little extra up front.

Design notes if you’re building or modifying tools

If you are designing a cordless tool or a DIY battery-powered machine from scratch, starting with BLDC and a modern integrated driver can actually simplify things. Several semiconductor vendors now offer “power application controllers” that wrap microcontroller, gate drivers, ADCs, protection circuitry, and sometimes even DC/DC conversion into a single package aimed exactly at BLDC power tools. That means you don’t have to stitch together half a dozen boards; you place one SoC, some FETs, and a motor.

For high-torque, low-speed applications like screw guns or compact winches, an outrunner BLDC with a gearbox can give you a lot of torque in a small envelope, at the cost of some mechanical complexity. For higher speed tools like small grinders or rotary tools, an inrunner with appropriate gearing or direct drive and careful balancing works well. The interesting part for a DIYer is the freedom to shape current limits and torque curves in firmware instead of hoping a mechanical clutch saves your wrist.

On the AC side, reusing a universal motor from a broken saw or vacuum cleaner for a shop project still has its place. It gives raw speed and decent torque from a compact frame, runs directly off mains with a suitable controller, and tolerates rough handling. But you should be conscious of brush sparks, acoustic noise, and EMI if you’re mounting it near electronics, flammable materials, or in an enclosed box. Adding soft-start or dimmer-style control can tame startup current a bit, though you won’t reach the efficiency or control finesse of a BLDC system.

One subtle side note: if your project needs precise low-speed control or holding torque, consider whether you actually want a BLDC in servo configuration or a proper servo/stepper system rather than treating either motor type as a “fast thing to slow down.” The border between BLDC and servo in hobby projects is mostly about feedback and control, not a different physical motor.

So which should you actually choose?

If you are buying a new cordless drill, impact driver, or compact saw and you care about runtime, power-to-weight, and longevity, a BLDC-based tool is usually the rational choice unless the price gap is extreme. You get more work per charge, a cooler housing, and features like better stall handling and speed control that come along for the ride with the motor controller.

If you are equipping a workshop with mostly corded gear and you are sensitive to cost more than noise or energy use, commutator motors are still entirely valid. A corded brushed grinder or drill can be brutally effective, especially for intermittent work, as long as you accept the maintenance and the sound.

If you are designing or heavily modifying equipment—CNC, robotics, oddball jigs—BLDC starts looking more like the default. The moment you want closed-loop control, current limiting, and integration with other electronics, the additional complexity of a BLDC drive is offset by cleaner behaviour and better efficiency.

So the short rule that actually survives contact with a real workshop is simple enough: choose commutator motors when you need something cheap, simple, and mains-fed; choose BLDC when you want to lean on batteries, intelligence, and long-term reliability. The rest is just matching those two truths to the kind of work you actually do.