Commutator Test Procedure: What You Actually Do In The Shop

If a commutator passes consistent bar-to-bar readings, holds insulation to ground under test voltage, and shows no mechanical abuse, you can usually put it back in service without drama. Everything in this procedure is just a disciplined way of getting to that point every single time.

Table of Contents

The real goal of commutator testing

Official standards talk about insulation classes, test voltages, leakage current, surge envelopes, all of that. In a repair shop or plant, your real question is simpler: “Will this armature behave when I energize it, and will it keep behaving after a few thousand hours.”

Most failures trace back to the same small cluster of problems. Loose bars and risers. Weak turn-to-turn insulation that only shows up under stress. Ground paths from bars to core or shaft. Poor surface condition that chews brushes or invites sparking. Commutator testing is there to corner those issues before they get buried inside a machine. EASA’s practical guidance lines up with this view: tight bars, clean surface, and basic electrical checks are the heart of commutator assessment.

This guide assumes you already know how your hipot, surge tester, and meters work, and that you have access to the motor’s documentation or at least its voltage and duty class. The focus here is not on explaining what a commutator is, but on how to structure the test routine so it is predictable and hard to fake.

Pre-test setup: getting the armature ready

Before touching test leads, the armature has to be in a stable state. Dry, reasonably clean, and at a temperature that will not distort readings completely. You remove brushes, clean carbon dust from the commutator face, and make sure there is no obvious oil residue. That step often feels boring, so people hurry it. The result is usually noisy data that does not quite match what the documentation promised.

If possible, note ambient temperature and relative humidity. Even a rough number helps when comparing bar-to-bar readings or insulation resistance over multiple years. Some shops quietly keep a line on their test form for that; it is a small habit that pays off when someone asks why today’s values do not match the numbers from three summers ago.

You also decide the order of tests up front. A common sequence is low-stress checks first, then high-stress: resistance and bar-to-bar tests, then hipot to ground, then surge testing if you use it. This stacks the risk in the right direction: you do not want a borderline coil failing in a surge test before you have basic resistance and ground readings captured. Electrom and other surge test vendors explicitly recommend doing insulation-to-ground checks before loading the winding with surge pulses.

Visual and mechanical inspection of the commutator

A commutator that looks wrong usually is wrong. You already know the classic defects: heavy grooving, flat spots, raised mica, lifted bars, pitting or burn marks, discoloration suggesting local overheating. Helwig and similar brush specialists stress bar-to-bar uniformity of the surface and the absence of burned or blackened regions as a simple condition for reliable commutation.

Here, the procedure is straightforward but worth treating as a real test, not a casual glance. Rotate the armature slowly and look for:

Commutator runout you can see by eye or with a dial indicator if you are set up for that. Step changes in bar height. Any sign that a riser has cracked or loosened. Brush track that is uneven across the face. You do not try to quantify everything. You just decide “this surface can go to electrical tests” or “this needs machining and undercutting first.”

If the armature fails this visual stage badly, you stop. There is no point in chasing perfect electrical readings on a mechanically compromised commutator.

Bar-to-bar resistance test: the backbone of the procedure

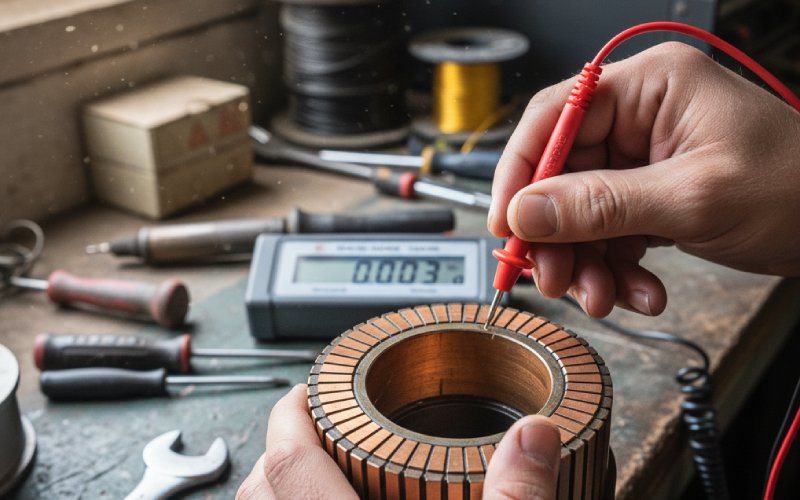

Almost every serious article on armature testing makes the same point: bar-to-bar resistance is less about absolute ohms and more about repeatability from segment to segment.

You connect a low-ohms meter or milliohm meter across two adjacent commutator bars. The armature is held stationary. You record the reading, then move one bar forward and repeat, walking your way around the full circle. Modern Pumping Today describes variants of this — 180-degree tests and local bar-to-bar checks — but the guiding rule is always the same: readings should sit in a tight band.

Three practical points often get missed:

The contact condition matters a lot. Oxidized or dirty bars introduce noise. Lightly burnish the surface before testing and keep your probes or Kelvin clips consistent.

Temperature will shift all readings together. That is acceptable. What you are tracking is the relative spread.

Outliers in either direction are interesting. A low reading hints at shorted turns within that coil. A high reading suggests a broken conductor, bad joint, or connection problem between bar and winding.

You do not need to know what the design resistance “should” be. You only need the spread to be small enough that you are comfortable, usually a few percent for many industrial DC machines, though your own historical data is more reliable than any generic rule. Some DC armature service providers use additional surge testing or growler methods when resistance spread is suspicious but not obviously failed.

Bar-to-core / bar-to-shaft insulation test

After bar-to-bar checks, the next concern is leakage or hard faults from the commutator bars to the core or shaft. Modern Pumping Today’s third test, measuring from each bar to the iron stack or shaft, is a simple version of this, treated as a go/no-go continuity check.

In a more formal procedure, you upgrade that simple continuity check into an insulation test with a megohmmeter or hipot source, choosing test voltage based on the armature’s rated voltage, insulation class, and your local standards or OEM recommendations. Electrical-engineering references on hipot testing remind us that this is a stress test for insulation, not just a high-ohms measurement; voltage level and dwell time must respect the equipment’s rating.

The process flows like this, even if no one says it aloud. You verify all safety interlocks and barriers on the tester. You connect one side of the test source to the commutator (often via a band or fine mesh around the bars) and the other side to the shaft or core, depending on how the armature is built. You raise voltage to the chosen value, hold for the specified time, and watch leakage current and any partial discharge or flashover.

Expected outcomes are boring: stable leakage in the microamp to low milliamp range, depending on size and standards, and no sudden jumps or breakdown. Any visible discharge, sharp current spikes, or creeping rise in leakage under constant voltage means you are now in insulation-problem territory. That does not always trigger immediate rewind, but it forces a serious conversation and usually some reconditioning at minimum.

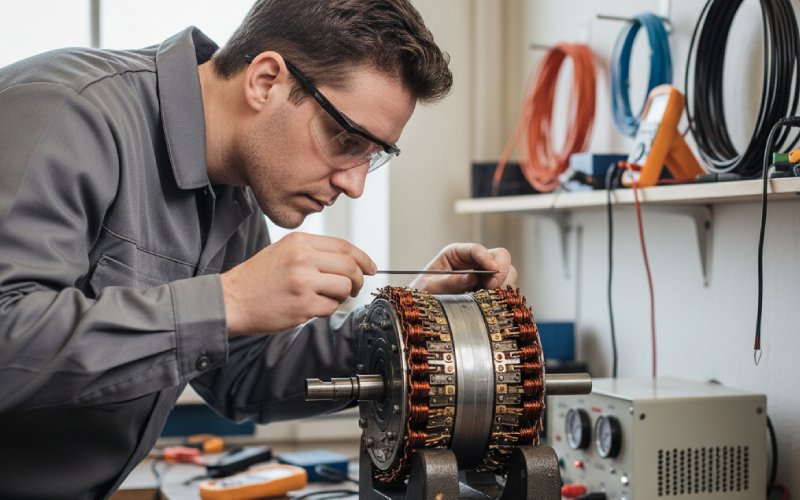

Surge testing of the armature

Bar-to-bar tests and hipot do not fully stress turn-to-turn insulation inside a coil. Surge testing is the method that goes after that weak spot directly. Motor diagnostic sources describe it as applying fast high-voltage pulses and comparing the resulting waveforms. Weak insulation produces waveform differences relative to a healthy reference.

On a commutator armature, you connect the surge tester across appropriate points on the winding, often via commutator bars or lead ends, and step test voltage up to a value tied to motor rating and internal standards. What matters in this blog is not the physics; you already know that. What matters is how you treat the test results in the broader procedure.

You make sure basic insulation to ground has already passed, so that a surge-initiated failure is more likely to reveal a weak turn than a gross ground fault. You compare waveforms between similar coils or between phases if the configuration allows. Equipment vendors point out that surge tests uniquely expose turn-to-turn and coil-to-coil weaknesses that low-voltage tests miss, so you treat an abnormal wave as real even when resistance looks fine.

Shops that test a lot of DC armatures often pair surge testing with bar-to-bar resistance on the same fixture, using specialized accessories from Baker or similar manufacturers. These attachments make it easier to contact bars safely and repeatably and to store data for comparison across rewinds.

Growler and low-tech methods

Not every workshop has a surge tester. That is okay. The growler, plus a meter and test strip or hacksaw blade, remains a common, valid way to reveal shorted turns in smaller armatures. Traditional growler instructions ask you to place the armature in the magnetic jaws, energize the core, and then “walk” a strip of ferromagnetic material around the slots to feel for excessive vibration or attraction where turns are shorted.

Some growlers also integrate bar-to-bar resistance features, using probes you walk around the commutator while watching a meter. The procedure is slow but simple. You accept that it will not match the sensitivity or documentation of a modern surge tester, yet it still catches major winding faults and is more than enough for many repair decisions, especially when paired with insulation checks and solid visual inspection.

Summary of common commutator tests

The table below condenses the typical tests into one place. It is not a standards document, just a practical snapshot drawn from motor-testing articles and equipment guides.

| Test type | Main purpose | Typical equipment | Usual stage in workflow | Key observation approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Visual / mechanical check | Surface condition, bar integrity, runout | Eyes, light, gauge, dial indicator | First, before electrical tests | Obvious defects, bar height variation, burning, damage |

| Bar-to-bar resistance | Coil continuity and relative balance | Milliohm meter, Kelvin bridge | Early, after cleaning and setup | Consistent readings around the commutator |

| Bar-to-core / shaft insulation | Leakage or faults to ground | Megohmmeter, DC or AC hipot source | After resistance tests, before surge | Stable leakage, no flashover or sudden current jumps |

| Turn-to-turn / coil stress | Weak insulation between turns or coils | Surge tester with commutator fixture | After insulation-to-ground checks, if available | Waveform differences, abnormal test signatures |

| Growler test | Shorted turns in smaller armatures | Growler, test strip, meter | Alternative or supplement to surge testing | Localized vibration or imbalance over suspect slots |

| Final resistance to core | Simple confirmation of isolation | Ohmmeter or megohmmeter | Often as a last quick check | Infinite or very high resistance from bar to core |

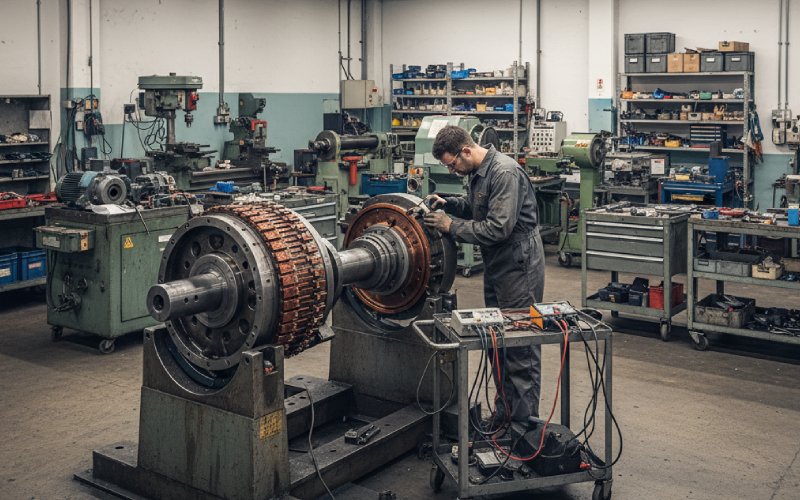

Putting it together as a repeatable process

The most effective shops treat the commutator test as a single flow, not a pile of unrelated checks. It looks roughly like this when you watch a skilled technician work, even if they never write it down. They inspect the commutator surface and risers with care. They set up for bar-to-bar resistance, move around the commutator steadily, and look for patterns, not just numbers. They switch to insulation-to-ground tests and respect the stress these tests place on the winding. Only then, if the facility has the gear, do they add surge testing for deeper insight into turn insulation.

There is also the question of when to test. Some repair guides recommend repeating bar-to-bar and hipot tests before installation, after installation, and after final assembly, especially on higher-value machines, to catch any damage introduced during handling.

In practice, your own test plan template is what ties this all together. It records which tests you run at which voltages, what spread you accept on bar-to-bar readings, and how you react to marginal results. Over time, those forms quietly become your local standard, more trusted than any generic article online.

Interpreting gray-zone results

Real commutators do not always pass or fail neatly. You will see small steps in resistance, minor cosmetic surface issues, or insulation values that are acceptable but lower than the rest of your fleet. Articles on motor testing sometimes treat these as simple pass/fail cases, but daily work is more ambiguous.

When readings are consistent but slightly noisy, you might clean contacts and repeat. When one or two bars read low but surge and growler tests are clean, you might log the deviation, advise closer monitoring, and still return the machine to service in non-critical duty. When hipot leakage is trending up compared with a previous overhaul, you may adjust test voltage, repeat after drying, or recommend a rewind even if the machine has not yet failed a standard test.

The important part is that you make these decisions visible. You annotate the test sheet. You link borderline results with clear remarks rather than silent acceptance. That is how a procedure becomes more than a formality.

Closing view

A commutator test procedure does not have to be complicated or poetic. It just has to be the same, every time, and honest about what you actually measure. Visual condition, bar-to-bar balance, insulation to ground, and—where available—surge or growler checks on turn insulation. If you respect those steps, record the numbers, and react consistently to what they show, your commutators will rarely surprise you, and when they do, the test record will usually explain why.