Commutator Surface Conditions: Reading What The Copper Is Telling You

If the commutator surface is uniformly filmed, moderately rough, and geometrically true, almost every chronic brush problem quietly disappears. Keep those three things in line and the rest of the system tends to behave, even when the nameplate and the real world are arguing with each other.

Table of Contents

Why surface condition matters more than any single adjustment

You already know what a commutator does, how brushes work, and what “good commutation” means on paper. What usually causes trouble in the field is not missing theory; it is misreading what the copper face is trying to say about the whole machine.

Almost every serious DC machine failure that shows up as sparking, grooving, or erratic brush wear has been visible as a surface trend long before shutdown. Film tone starts drifting. Roughness changes. Local heating patches form. Those subtle shifts are the real early-warning system. Charts and posters give nice photographs of “light film” or “bar burning,” but they rarely connect them to loading patterns, humidity swings, or how the last machining job actually left the surface.

So here the focus is simple: take the standard condition charts, compress the theory, and turn the observations into decisions you can act on quickly.

What “good” really looks like, beyond the posters

Most guides call a uniform light to medium brown film acceptable, with tone set by brush grade and current density. That line is technically correct but not specific enough for reliability work. In practice, a “good” surface usually has four features at the same time.

First, film tone is consistent around the full circumference. You might see minor shade variation between pole zones, but there should be no sharp transitions at a single bar or group of bars. Carbon suppliers describe light and dark films as fine as long as they are even, and that is what matters most.

Second, the surface is not mirror-polished. Recommended finishes for turned commutators are typically in the 40–60 micro-inch (about 1.0–1.5 micrometre) Ra range. That corresponds to a visible but fine lathe pattern that gives the brush somewhere to seat and build film without turning the copper into a grinding wheel. When roughness gets much higher, brush wear goes up hard; when it gets too low and bright, film becomes unstable and streaky.

Third, there are no geometric surprises. Bar edges are clean, bar heights are level, and the commutator runs concentric with the shaft seats. Any visible out-of-round or bar step will usually show up first as selective brush marking, then as clear mechanical wear bands.

Fourth, the surface temperature under normal load stays ordinary. That sounds vague, but you know the difference between warm and discomforting when you put a hand near the end bracket. Persistent hot bands often precede copper drag and bar burning.

Once those four elements drift, problems start to layer. Film stops matching the environment, mechanical finish fights the brush grade, and current redistributes between paths in ways that theories flatly dislike.

A quick triage table you can actually use

Most condition charts list dozens of surface states; in the field you rarely have the patience to stand and classify every ripple. Grouping them into three bands makes decisions easier: acceptable, watch, and act-now.

Here is a condensed table that ties visual cues to likely system causes and first responses, pulling from several standard charts and wear guides.

| Condition band | Visual cue on copper | Likely system story | First move, in plain terms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acceptable | Uniform light or medium brown film, slightly glossy, fine circumferential machining marks, no local hot spots | Brush grade matched to duty; current density and humidity within normal band; surface finish in recommended range | Log it as baseline, note photos, and avoid “improving” it with unnecessary polishing or cleaning |

| Acceptable but unusual | Dark uniform patina or slightly blotchy film without sparking or abnormal brush wear | Higher filming brush, higher current density, or mild chemical vapour; film still stable and continuous | Leave it alone, verify ventilation and load history, and watch for any move toward streaking or localized heating |

| Watch | Light streaking along rotation direction, film slightly patchy between zones, brushes still wearing normally | Small current imbalance, minor environmental changes, slight brush seating issues; film starting to respond | Check brush contact pattern, verify spring pressure, clean air paths, and record whether the pattern grows or fades over a few weeks |

| Watch | Faint circumferential grooves you can just feel with a fingernail, no heavy edge ridging yet | Finish too rough or brush grade a bit abrasive; copper and carbon acting like a slow lapping process | Plan a controlled skim cut and proper finishing at next shutdown; do not chase it with improvised abrasives while running |

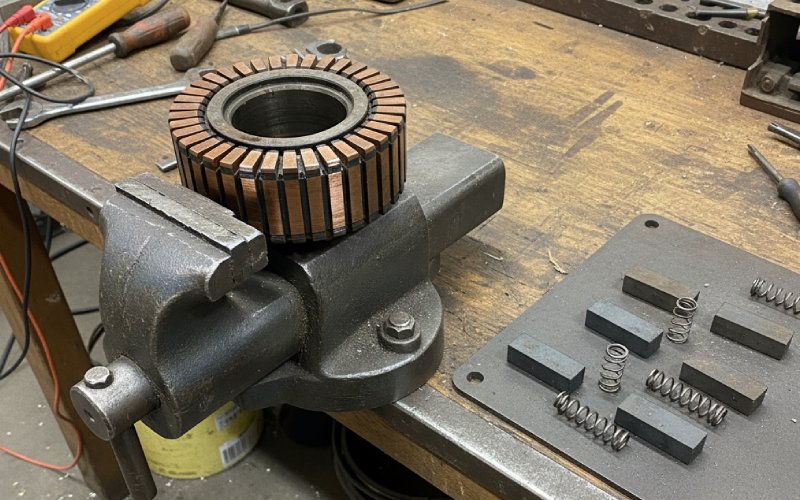

| Act now | Bar burning, local blackened patches, heavy sparking at specific bar groups | Serious commutation imbalance, bad neutral setting, poor equalization, or local coil issues; film destroyed locally | Take load down, investigate brush position and field settings, verify equalizer connections, and prepare for repair of damaged bars |

| Act now | Threaded or rutted surface, pronounced grooves, copper dragged across slots, brush faces showing matching patterns | Overheated and softened copper with vibration or overly abrasive brushes, causing metal flow and electrical machining of the surface | Schedule a shut-down, correct brush grade or spring pressure, re-machine the commutator, and clean out metallic dust before restart |

The point is not to memorize the rows. The point is to move quickly from “what I see” to “what the system is likely doing” and then to “what I am going to change first,” in that order.

Roughness, film, and why “smooth and shiny” is not the goal

A common temptation is to chase a mirror finish on the commutator, especially after a heavy machining job. It looks precise. It satisfies a certain urge for symmetry. It also tends to shorten brush life.

Guides on commutator finishing are quite clear that roughness has to sit in a band, not at an extreme. EASA’s AR100 practice calls for a surface finish around 40–60 micro-inch Ra; other technical notes and tooling suppliers recommend a peak-to-valley range around 6–10 micrometres with clear but fine lathe marks. Too rough, and the commutator behaves like a grinding wheel; brushes wear excessively and film is unstable. Too smooth and bright, and the film will not anchor well, which encourages streaks and patchy regrowth.

So the roughness band is really a compromise between mechanical and electrical wear. On one side, you want enough micro-texture for carbon transfer to stop slipping and start sticking. On the other, you do not want to cut the brush face into ridges that then attack the copper in return. The right finish is not about appearance; it is about producing a surface where film can continually rebuild without either partner doing most of the damage.

This is why controlled finishing methods matter more than creative shop solutions. Cloth or paper wrap-around methods, used correctly, can smooth small irregularities without destroying concentricity. Random hand pressure with strips, or local polishing with a finger pressed on abrasive, tends to round bar edges and generate uneven film, which looks good for a day and wrong for months.

Film as a moving target, not a static colour chip

One of the more useful messages from classic commutator condition guides is that film is dynamic and driven by the environment: current load, temperature, humidity, brush spring tension, and contamination all push it around. That means the “ideal” surface is really a shifting compromise between the machine’s design and its actual duty.

High humidity, especially in warm climates, tends to soften films and can move the balance toward darker, more conductive layers. Low humidity and low temperature do the opposite; they favour lighter films and can increase the risk of streaking or dusting. Research on brush wear under variable current and environmental conditions shows how heavily temperature and humidity skew wear behaviour in real service.

Then there is the load pattern. Long periods at low load can leave brushes under-worked and encourage poor film formation; intermittent overloads or frequent reversals can strip film completely in certain zones. Spring pressure interacts with all that: too low and contact is unstable; too high and both copper and brush erode faster than the nameplate would suggest.

So when the surface starts showing new patterns, the right question is often not “what is wrong with the commutator,” but “what changed in the environment, the duty cycle, or the brush setup that the commutator is faithfully reporting.”

Using the brush face as your second opinion

Condition guides repeat a simple but often ignored fact: the face of the brush tends to mirror the condition of the commutator surface. If you are uncertain about what you are seeing, pull a brush and let it confirm or contradict your first impression.

If the copper is threaded, the brush face will show parallel ridges. If there is copper drag across slots, the brush will often pick up that metal and show streaky bright bands. If film is uniform but the face shows uneven contact area, then the problem is more likely in holder alignment or spring pressure than in the commutator itself.

This cross-check is especially useful after machining and finishing. A fresh surface might look fine, but when you run at low load for a while and inspect the brushes, they will tell you whether the actual contact patch is where you expect it and whether film is forming evenly. It is a cheap, quick diagnostic, and it stops you from blaming the copper when the holder, shunt, or spring is really at fault.

Maintenance strategies that respect the surface

Good surface conditions rarely come from one big repair; they come from a string of conservative decisions. That may sound dull, but it works.

Machining should aim for concentricity with the shaft seats, correct bar geometry, and the roughness band discussed earlier, not for visual perfection. After machining, undercutting and chamfering of mica should be clean, with groove depth appropriate to the machine’s design, but pushed no deeper than necessary.

After that, film formation and stabilization are helped by controlled running, proper seating of brushes, and correct cleaning. Many guides recommend a period of no-load operation after new brushes or major surface work, to allow full contact to establish and film to build without heavy electrical stress. The temptation to rush back to full load is understandable; the long-term cost is often accelerated wear and another service visit.

Cleaning has to be selective. Dry vacuuming and filtered air are the default choices. Solvent use on commutators is risky; it can remove film and carry contaminants into places you do not want them. Excessive wiping with cloths impregnated with anything other than approved materials has the same issue. The surface may look better; electrically it is now starting from zero again.

For collectors and some commutator applications, periodic polarity reversal has been used to keep film more uniform around the circumference, spreading wear and controlling roughness. It is not a universal technique, but where design allows it, the method directly acknowledges that film is something you manage over time, not a static condition you set once.

Edge cases: when surface condition hints at bigger problems

Sometimes the copper is not the root cause at all; it is just the visible part of a deeper issue. A few examples keep recurring.

In high-duty traction or mining machines, there is often a combination of dirty environment, aggressive loading, and voltage disturbances. Studies of low-power AC commutator motors show brush wear far exceeding commutator wear, with a wave-like pattern along the surface that reflects electromagnetic and mechanical interactions. In that sort of duty, you can keep resurfacing the commutator and never solve the real problems without addressing ventilation, filtration, and control settings.

Starter-generator applications on aircraft and helicopters produce another edge case. Airworthiness directives have documented abnormal brush and armature wear, including grooves on the commutator surface, traced back to specific operating conditions. In those contexts, surface condition is not just a maintenance concern; it becomes a formal reliability and safety issue.

Flashover is a third example. Guidance on flashover causes and cures highlights how damage to brushholders and commutators is strongly linked to poor paths for arcs to go anywhere except across expensive surfaces. Here, copper condition, insulation state, and the mechanical layout of holders all interact. If you only repair the commutator and ignore the system that lets high-energy arcs form and roam, you will see the same patterns again.

These cases all argue for reading surface condition as one input among many. When something looks extreme, it usually is. But the fix may live in wiring, controls, holders, environment, or duty cycle just as much as in the copper itself.

A practical way to work with commutator surfaces

If you step back from the charts and photos, commutator surface conditions reduce to a small set of recurring ideas. Keep mechanical geometry honest. Hold roughness in the band where film can grow without grinding the brush. Choose and maintain brush gear so contact is stable and current distribution sane. Watch how environment and duty shift film over time, and treat the surface as a moving indicator, not a one-time inspection item.

The rest is routine: inspect visually with purpose, listen to what the brush faces say about the copper, make small adjustments early instead of large corrections late, and document what “good” looks like on each actual machine, not just how it looks in generic charts. If you do that consistently, most commutation issues never have a chance to become case studies.