What is a commutator segment?

A commutator segment is the individual copper bar in a commutator that takes one coil’s current, carries it past the brushes, and hands it over to the next coil at exactly the right mechanical angle, while staying electrically isolated from its neighbours by thin, stubborn insulation.

Table of Contents

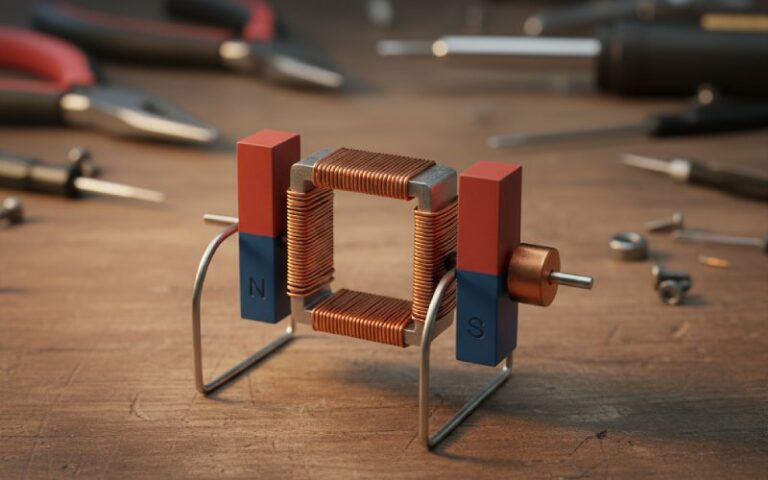

Thinking of the commutator one bar at a time

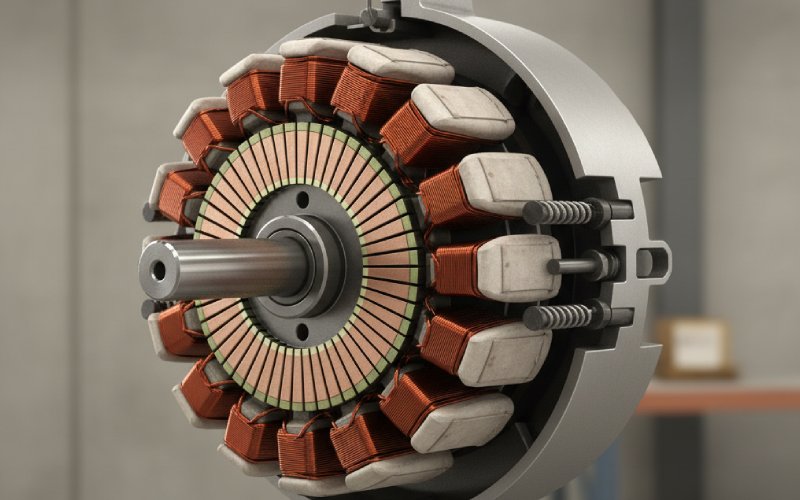

If you forget the whole motor for a moment and just hold on to one bar, the picture becomes simpler and more honest. Each segment is a shaped piece of hard-drawn copper, keyed into a hub, insulated from the next bar by a narrow slice of mica or similar material.

The complete ring is just a repetition of that unit cell. One bar, one coil termination (or pair of coil ends, depending on your winding scheme), one chance to get current transfer right, and one more place where things can go wrong. When people talk about “commutator problems”, they are usually seeing the sum of many small segment-level decisions, taken years earlier in design and manufacturing, and then stressed by brush choice, environment, and duty cycle.

Geometry that quietly controls behaviour

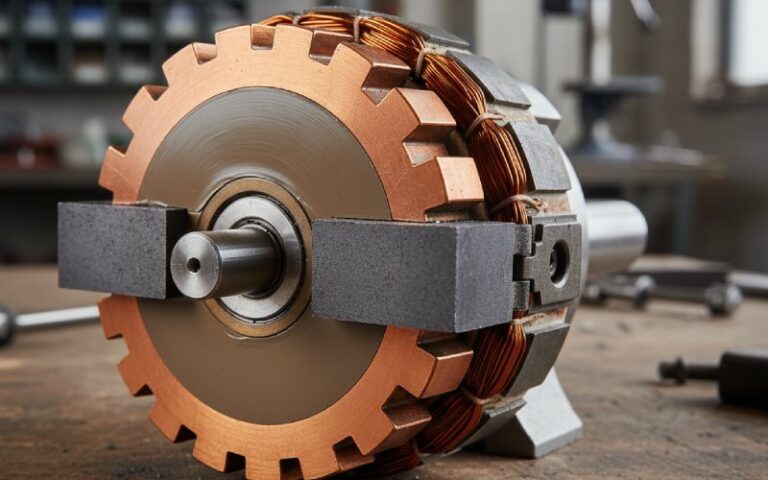

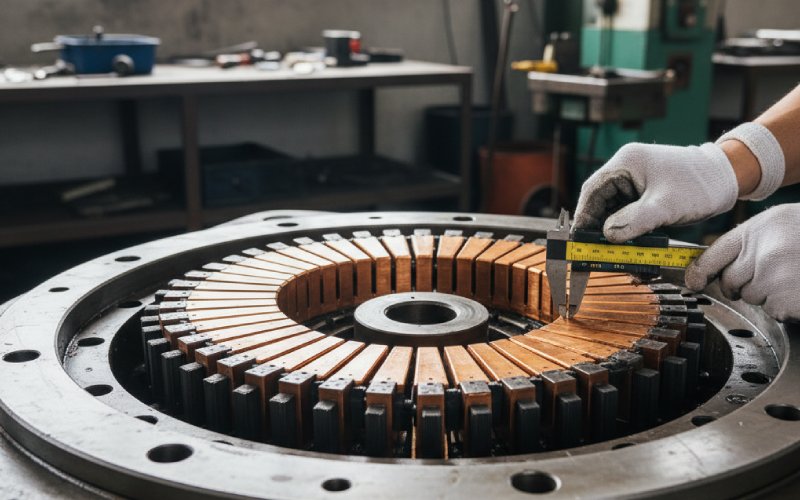

Most reference material tells you the commutator has “many segments” and moves on. The numbers behind “many” are not decorative. Segment pitch, face width, and run-out decide whether your brushes are working with the machine or constantly fighting it.

A common design rule is to keep the circumferential pitch (segment copper width plus the mica gap) at or above about 4 mm in industrial DC machines, with practical outer face widths typically between 4 mm and 20 mm. Below that, you start to run into brush edge effects, manufacturing tolerances, and carbon-film behaviour that stop matching the neat diagrams.

The segments themselves are usually wedge-shaped in cross section, thicker towards the outside diameter, and locked into a dovetail or similar groove in the hub. That geometry is about survival: it lets the bars resist centrifugal force and thermal cycling without walking out of the stack. When that mechanical restraint is marginal, you get bar movement, high spots, and then sparking that no amount of brush “adjustment” will cure.

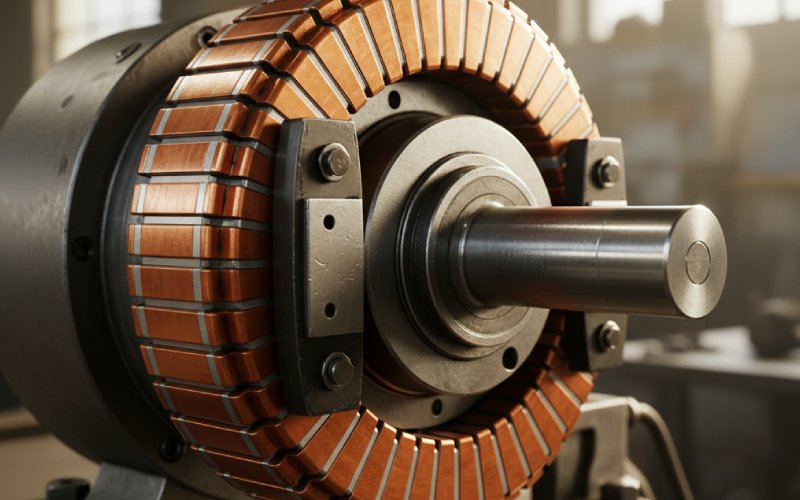

Materials: copper that carries, mica that refuses

By now you already know the textbook sentence: segments are made from high-conductivity hard-drawn copper, separated by mica insulation. What matters in practice is how stubborn each of those materials is in doing its own job.

Copper wants to expand with temperature, smear slightly under brush pressure, and form a thin film with brush material. Mica is almost the opposite. High-grade muscovite and modern segment mica stay dimensionally stable and resist wear at temperatures and pressures that would already have softened many plastics. That mismatch is useful: the mica keeps bars isolated under mechanical stress, but it forces you to undercut it below the copper surface, otherwise the brush will ride on the harder insulation instead of the conducting bar.

So a “commutator segment” is never just the copper. It is the copper plus the side mica, plus the undercut, plus the tiny edge chamfers, plus whatever film the brush and environment have deposited on its face.

One table to pin the segment down

Rather than more abstract theory, it helps to fix a few design choices against what you actually see at the segment face.

| Aspect of the segment unit | Typical design or condition | What it quietly changes in practice |

|---|---|---|

| Copper alloy and temper | Hard-drawn, high-conductivity copper bars, wedge-shaped, keyed into a hub | Controls resistive loss, bar deformation under brush load, tendency to groove or smear under high current density |

| Insulation between bars | Segment mica or similar, often around 0.8 mm thick in many designs | Sets creepage distance and voltage capability per segment; stiffness and wear resistance dictate how aggressively you must undercut and maintain it |

| Segment pitch and count | Pitch around 4–20 mm at the surface; number of bars set by voltage, speed, and coil scheme | Affects commutation overlap, brush contact pattern, and sensitivity to minor eccentricity or vibration |

| Surface preparation | Turned, then polished; mica undercut slightly below copper; edges broken but not rounded away | Influences film formation, sparking tendency, brush wear rate, and how faults first become visible as streaks or bands |

| Hub and clamping method | Dovetailed refillable construction, glass-band, or shrink-ring types in larger machines | Decides whether segments can be replaced individually, how they react to overspeed testing, and the long-term stability of bar alignment |

| Coil-to-bar joint | Brazed, welded, or peened terminations into risers or directly to bars | Sets contact resistance and is a common starting point for localized heating, bar burning, and asymmetric brush load |

Reading that row by row is often more useful than yet another diagram of a commutator ring.

Segment-level view of commutation

When current transfers from one coil to the next, the event is spread over a finite brush width and several segments. The brush typically spans more than one bar at any instant, effectively shorting adjacent segments during the switching interval.

From the standpoint of a single segment, its “career” during operation is repetitive but not identical cycle to cycle. It carries full coil current, then part of it while in overlap, then almost none as the brush moves on. The heating, film formation, and micro-wear steps through that pattern thousands of times per second in high-speed machines. Any slight difference in resistance at the coil joint, or a microscopic step between this bar and the next, will bias that cycle. The result appears later as coloured bands, tiger-striping, patchy film, or one proud bar that begins to arc.

So the commutator segment is where ideal commutation theory collides with production tolerances, ageing insulation, and brush setting technique.

Manufacturing and “seasoning”

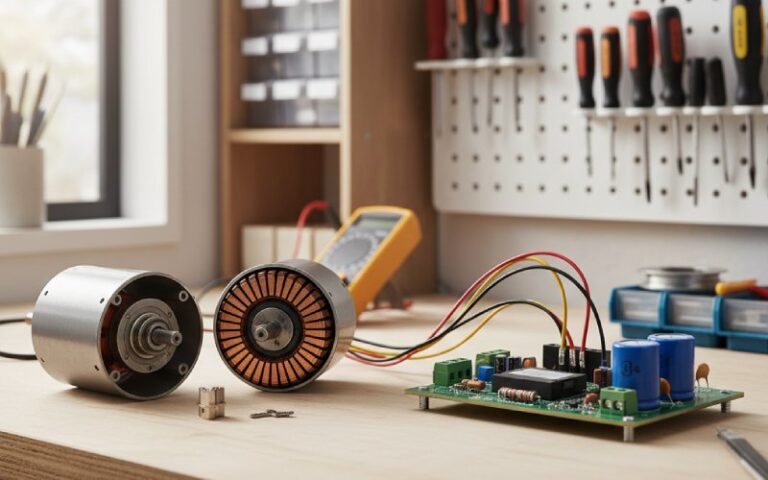

In large machines, segments are often designed to be refillable. An end ring or wedge system lets you remove one bar and its mica pack, insert a new one, and then re-machine the surface. That only works if the original geometry respected reasonable pitch and hub dimensions; otherwise, repair access is theoretical.

After assembly, many high-performance commutators are conditioned by heat cycles, torque loading, or overspeed spin tests. This “seasoning” isn’t about comfort. It forces any bar that wants to move to do so before the machine ever reaches a customer site. A segment that creeps under centrifugal load in the field quickly becomes a high spot, then an arc site, and finally a burned bar that drags its neighbours into trouble.

In compact consumer motors, molded commutators with crimped segments trade repairability for production speed and cost. Here, a failed segment usually means a failed motor; nobody is setting up a lathe for a drill that costs less than the repair labour.

Failure patterns written on the segments

Maintenance people rarely ask “what is a commutator segment” in isolation. They ask why a band of bars is dark, why brushes are sparking, or why one section of the ring keeps burning. At that point, the answer is scratched into the copper.

Loose or high-resistance joints between a coil and its bar usually create local heating. This often shows up as burn marks starting at a single bar and spreading to its neighbours as the brush tries to carry current across the damaged region.

Rough or eccentric commutators cause brushes to bounce, which erodes bar edges and increases sparking. Excess carbon dust packed into the mica undercut can, over time, partially short adjacent segments and change the effective commutation conditions just at the point where the current should be switching quietly.

Each of these is really a segment story: one bar slightly high, one joint slightly resistive, one area where mica undercutting or cleaning was rushed.

Design habits that keep segments uninteresting

For most engineers and technicians, the ideal commutator segment is boring. It sits in tolerance, carries current, forms a stable film with the brush grade, and never draws attention in inspection reports. Achieving that boring state comes down to a handful of disciplined choices: realistic segment pitch, conservative current density, reliable coil-to-bar joints, consistent undercut depth, and a hub system that actually keeps bars where you put them.

Once you see the commutator as a ring of individual segments, each with its own small mechanical and electrical story, the original question shifts slightly. Instead of only asking “what is a commutator segment?”, you start asking what your design and maintenance decisions are teaching each segment to do under real operating stress. That is where the device stops being a generic copper ring and becomes a component you can improve, not just replace.