How to determine the number of commutator segments in a DC motor

For a normal DC motor, the number of commutator segments is the number of armature coils. In a typical double-layer, single-turn design that also means “equal to the number of slots” and “equal to half the number of conductors”, then trimmed by mechanical pitch, voltage-per-segment, and brush constraints.

Table of Contents

The real rule under all the formulas

Textbooks say it plainly: the commutator has one segment per active armature coil. Design notes and exam problems repeat it in slightly different words: number of commutator segments equals the number of slots or coils, which for the usual single-turn coils is half the number of conductors.

So the core rule you design around is:

- Each distinct armature coil pair → one commutator bar.

- The brushes only ever ride across joints between these bars.

- Everything else is guard rails so that this mapping works at speed, temperature and current.

You already know where coils sit, how EMF builds up, how lap and wave windings connect. Here we are just forcing that knowledge into a number you can actually put on a drawing.

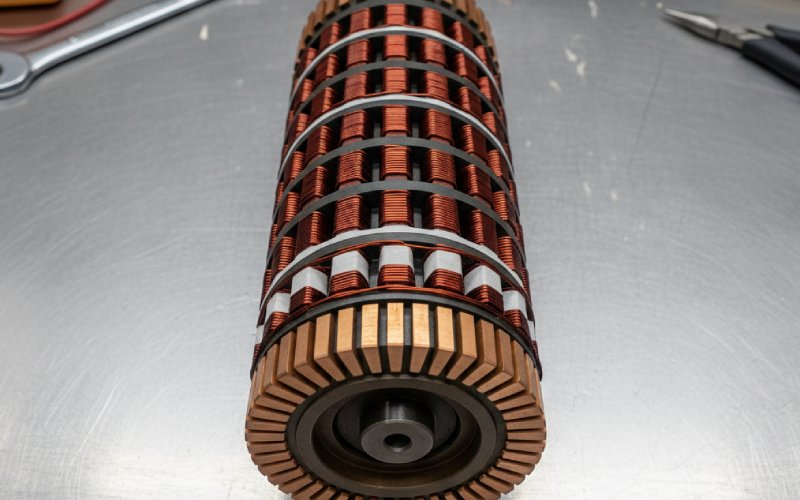

Coils, slots, conductors, segments: locking the count

Let the symbols sit in one place for a moment:

- = number of commutator segments

- = number of armature coils

- = number of armature slots

- = total number of armature conductors

- = turns per coil

For most machine designs you see in standard notes, with double-layer winding and one coil side per slot layer, the relationships collapse to something simple. One coil uses two slots. Total conductors is Z=2tCcoil. So

C=Ccoil=Z/2t

If you choose single-turn coils, (t = 1), and the headline rule engineers actually use appears naturally:

C=Ccoil=Z/2

In many double-layer layouts with one coil per slot, each slot contains the sides of two coils, so the number of slots matches the number of coils. Then you can say

C=Ccoil=S

which is what a lot of teaching material states directly: number of segments equals number of slots or coils.

Lap or wave winding does not change this equality; it just changes how those coils are linked around the armature and how many parallel paths appear.

So if you already fixed (Z) and (t), segment count is basically nailed by geometry. The rest of the work is checking that this number does not make the commutator impossible to build or to run.

Step 1 – Start from the winding you actually intend to use

In design practice you do not begin with “how many segments”. You start from voltage, power, speed, poles, cooling, manufacturability, and you land on:

- A chosen slot count and core size from the output equation and specific loading.

- A target conductor count (Z) that gives the right EMF with your flux per pole and speed.

- A chosen winding type: simplex lap for heavy current machines, simplex wave where you want higher voltage with fewer parallel paths, multiplex variants when currents or voltages get pushed harder.

Once that is frozen, the coil group diagram will tell you Ccoil. At that point you already know the theoretical segment count. You have not checked yet whether anyone can machine that commutator.

Step 2 – Check segment pitch and mechanical sanity

The standard design note formula for commutator segment pitch is

τc=πDc/C

where (D_c) is commutator diameter and τc is measured along the circumference, usually taken as “segment copper plus one insulation gap”.

There is an empirical lower bound: segment pitch should not fall below about 4 mm for mechanical strength and manufacturability of the segments and mica insulation.

This simple inequality is what starts to bite when you push (C) upward:

τc=πDc/C≥4 mm

Given a chosen diameter range (often some fraction of armature diameter, for example 0.6–0.8 of (D) in many notes), this immediately gives you a maximum allowable segment count. If the “one coil per slot” rule produces a (C) beyond that limit, you do not argue with physics. You go back and adjust slots, coil turns, or both.

Step 3 – Check voltage per segment and commutation

On the electrical side, each commutator segment carries the potential of its connected coil side set. When the brushes shift, the armature reaction and commutation zone combine with this voltage to decide how much sparking you get.

Design guides and study notes point out that small DC motors commonly end up with something like 20 to 120 segments. That range is not mystical; it is a compromise between manageable voltage per segment and acceptable mechanical complexity. More segments spread the total armature voltage over more bars, which reduces voltage between adjacent segments and usually gives smoother commutation.

You already know how to estimate the voltage between adjacent segments in a given winding. Here it just acts as a check: if the computed voltage per bar is high enough to be uncomfortable for the brush material and surface speed, you either increase (C) (if mechanically possible) or revise the whole winding.

Step 4 – Bring in the brushes and current density

The next constraint is quietly brutal. Every segment you add narrows the brush tracks. Every segment you remove pushes more current per segment for a given armature current.

Brush design rules of thumb give you:

- Maximum brush current density, typically several amps per square centimetre depending on carbon or graphite type.

- Maximum recommended brush width, often limited to a few segments wide so that commutation remains under the influence of the interpolar field.

The number of segments under a brush must allow enough total brush area, at acceptable current density, to carry the armature current. Segment pitch and brush width constraints interact here. If the segment count is huge, brushes become very narrow relative to circumference; current density and thermal rise on those tiny contact patches start to violate your limits.

Again, the segment number you got from “coils” may be perfectly legal electrically but awkward when you plug it into brush area equations. That is often what sends a designer back to revisit coil turns or slot count.

A compact design table

It is sometimes easier to see all these constraints lined up.

| Design quantity | Typical constraint or relation | Effect on segment count (C) |

|---|---|---|

| Coils vs segments | C=Ccoil. For single-turn coils, . For many double-layer windings, . | Sets the starting “ideal” count directly from winding data. |

| Commutator diameter (D_c) | Often chosen as a fixed fraction of armature diameter, with peripheral velocity under roughly 15 m/s. | For a given (C), defines segment pitch; may force (C) downward if the commutator would be too fine. |

| Segment pitch τc | τc=πDc/C, must stay above ≈4 mm for mechanical strength and manufacturing practicality. | Gives an upper limit on (C) for a chosen (D_c). |

| Voltage per segment | Determined by EMF distribution and winding; lower is better for commutation and insulation stress. | May push (C) upward, especially at higher machine voltages. |

| Brush current density | Limited by brush material, often around 5–6 A/cm² for normal carbon. | Excess current per segment may require more segments or different winding to distribute current paths. |

| Brush width vs commutation zone | Brush should span a few segments, but not much more than the commutation zone fraction of pole pitch. | Interacts with segment pitch and (C); extreme counts give impractical brush geometries. |

Once the numbers in this table are self-consistent, the segment count is effectively fixed.

A worked example, but kept honest

Take a shunt DC motor rated 30 kW, 400 V, 4 poles, running at 750 rpm. Assume you have already completed the electromagnetic design and ended up with:

Total conductors .

Single-turn coils, double-layer, one coil per slot.

So there are coils. That gives C=360 segments immediately.

Suppose the armature diameter D has been settled at 0.28 m. You pick a commutator diameter following the usual proportion guideline.

Segment pitch is

That number is already telling a story. Less than the recommended 4 mm minimum for segment pitch by more than a factor of two.

You now have options, none of them purely cosmetic:

Increase (Dc) significantly. That immediately increases peripheral velocity; you must check it stays under your mechanical limit and that brush speed is acceptable. Reduce the number of coils for the same voltage by increasing turns per coil and reducing slot count, so that (Z) stays similar but Ccoil falls. Revisit the original slot choice entirely.

Suppose you change the design to 240 coils (and therefore 240 segments), by using (Z = 480) conductors with double-turn coils and fewer slots. Now with the same (D_c):

τc=π×0.196/240≈2.56 mm

Better, but still below 4 mm. You push (D_c) up to 0.24 m, still within a sensible fraction of armature diameter. Segment pitch becomes

τc=π×0.24/240≈3.14 mm

Still tight. At this point, many designers would accept a slightly lower practical minimum, or adjust both (D_c) and (C) once more. The details depend on manufacturing capability and standards inside the company. The important thing is that the adjustment loop is clear: segment count is being driven by both the winding and by this hard geometric constraint.

Now look at voltage per segment. With 400 V at the terminals and 240 segments, the average voltage between adjacent segments is only a few volts depending on winding layout; comfortably within typical commutation limits for carbon brushes at this speed. If you had kept 360 segments and somehow made the commutator thicker to get the same pitch, the voltage per segment would be even lower, but the mechanical complexity and brush width problems would not go away.

So the “correct” number here is not an exact integer pulled from a table. It comes out of repeated passes through winding, geometry and commutation checks, and you stop when conflict disappears.

What happens with multiplex and fractional-slot windings

Once you move into multiplex lap windings or fractional-slot layouts, the simple visual mapping “one slot, one coil, one bar” starts to look messy, but the underlying rule does not change: each distinct coil group that needs its own commutator connection still uses one segment.

The arithmetic looks different mainly because:

The number of parallel paths in the armature changes, so your conductor count per path shifts and that feeds into the turns per coil decision. Fractional-slot choices can mean that the relationship between slots and coils is not 1:1 any more; some slots carry coil sides that belong to more than one group pattern.

Even in those cases, once the final coil grouping diagram is drawn, if you count coil groups around the armature you count commutator bars. The mechanical, pitch and brush checks are unchanged.

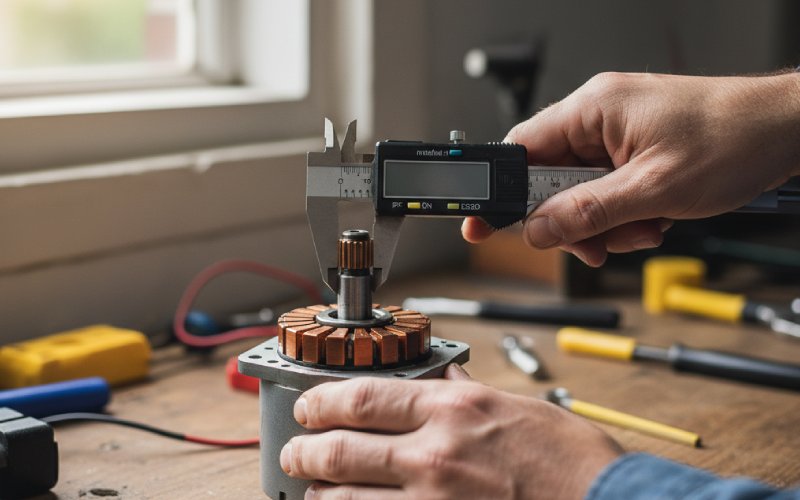

Reverse engineering: inferring segment count from an existing motor

If you are staring at a real DC motor rather than a blank sheet, the problem runs the other way. You measure, you count, and you try to decide whether the commutator is overrated or stressed.

You can count segments directly, which is easiest when the bar count is low. When it is not, you measure circumference, divide by segment pitch, and check that against slot count. If the machine follows standard practice, you should see:

Segment count close to slot count on a double-layer armature, or at least matching the coil count you infer from the winding sketch. Segment pitch in the few-millimetre range, rising with power and size.

If the voltage and speed are known, you can also estimate voltage per segment and brush current per bar. Comparing that with typical textbook or manufacturer data for commutation limits gives you a feel for how close the original designer ran to the line.

A practical mental checklist

When you are deciding, or sanity-checking, the number of commutator segments for a DC motor, the thought process can be compressed to this:

First, take the winding as designed and compute coil count. Set C=Ccoil.

Second, with your chosen commutator diameter, compute segment pitch. If it violates the minimum mechanical pitch you are comfortable with, change either the winding (coil count) or the commutator size. If you cannot fix it without ugly trade-offs, you are probably forcing the wrong slot or conductor count onto this frame size.

Third, estimate voltage per segment and check it against your experience with similar motors and brush types. If it is high, you may need more segments or a different winding strategy.

Fourth, check brush current density and brush width versus segment count and commutation zone. If the brushes become too narrow or too heavily loaded, segment count must move or parallel paths must change.

If all four checks pass, the number of commutator segments you have is not just mathematically consistent with the armature winding; it is buildable, maintainable, and reasonable for the voltage and rating you are working with. At that point the question “how many segments should this DC motor have?” is basically answered.