Commutator Resurfacer: Getting Serious About On-Machine Commutator Repair

Most commutators do not fail because nobody ever resurfaced them. They fail because someone resurfaced at the wrong moment, with the wrong abrasive, chasing the wrong problem. A commutator resurfacer only becomes useful when you treat it as a controlled machining tool, not a glorified sanding stick.

Table of Contents

What a commutator resurfacer really is (once you stop treating it like a stone on a stick)

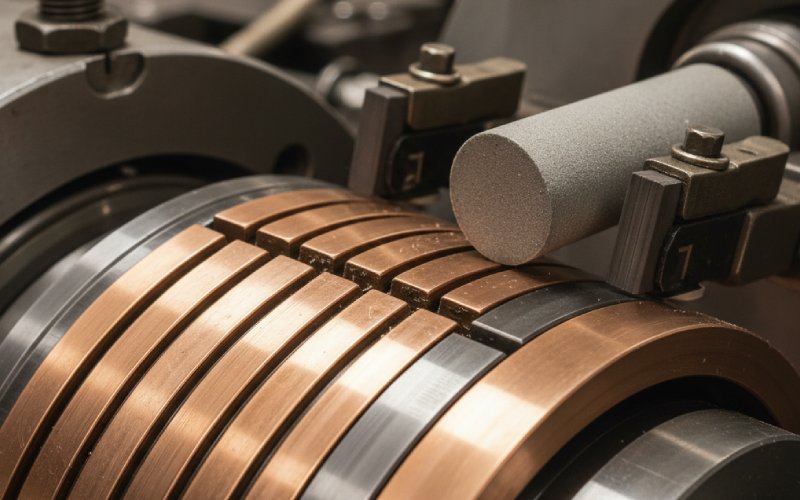

If you already live with DC motors and slip-ring machines, “commutator resurfacer” means one of two families of tools. On one side you have the small hand tools: non-conductive handle, replaceable pads at the tip, one medium or finish grade each, usually around 5/16″ by 7/8″ on handles in the 8–10 inch range. Makers like Martindale and Ideal sell them as “smoothie” tools with a polish stone on one end and a finish or medium stone on the other, specifically dimensioned for getting into motor frames while keeping your hands insulated.

On the other side you have true portable resurfacing devices: the NSN-style units that mount on the brush rigging or a dedicated arm, carry one or more stones in a guided holder and traverse the full commutator face while the rotor runs in its own bearings. The specification literally calls them “a portable device designed to true up commutators or slip rings without dismantling,” with replaceable stones running across the surface.

Both are commutator resurfacers. One is a guided abrasive head on a carriage, the other is a guided abrasive on your hand. In either case, you are machining copper under live operating geometry. That is the mindset that separates “quick wipe” from reliable repair.

Where a resurfacer actually fits among the seven classic methods

A widely used commutator maintenance guide from Morgan lists seven accepted reconditioning methods, in order of preference: turning with a diamond tool, turning with carbide, grinding with a rotating wheel, turning with high-speed steel, grinding with a fixed stone, grinding with a handstone, and finally scouring with abrasive cloth.

A commutator resurfacer lives in the last three of those. It is a controlled way to do fixed-stone or handstone grinding on a running machine, and to do the final “cloth equivalent” finish, without dragging the armature onto a lathe. If you already have serious eccentricity, badly stepped bars or lost undercut depth, the resurfacer is late to the party; diamond or carbide turning has to go first. But if your problem is banding, mild ridging, glazing, or a surface that drifted too smooth, the resurfacer is the right size of hammer.

Morgan also point out that concentric grooves around the commutator are usually harmless, while axial steps as small as 0.025 mm between bars can upset the brushes enough to cause chipping and arcing. That is exactly the sort of defect that a properly guided resurfacer can correct, without touching the rest of the geometry.

Roughness targets: not mirror-bright, never glassy

Most manuals under-communicate one awkward fact: the commutator should not be shiny like a polished shaft. Mersen’s maintenance notes recommend that operating roughness should stay above about 0.4 μm Ra; below that, problems become more likely. They also give working bands: roughly 0.9–1.8 μm Ra for industrial commutators, and 0.5–1.0 μm Ra for small machines under 1 kW.

Morgan’s older guide says essentially the same thing in different units: the “skin” that the brushes build should not end up smoother than about 25 micro-inches (around 0.64 μm), and they explicitly warn against a highly polished, almost burnished finish from diamond turning as a working surface. Another technical note from Trade Engineering underlines that overly smooth, brilliant surfaces often give higher friction and unstable brush behaviour compared with lightly textured ones.

So the resurfacer’s real job is not to make the commutator beautiful. Its job is to put the surface back into that narrow band where brushes seat predictably, film forms evenly, and nothing dramatic happens at starting current.

How on-machine resurfacing compares to other options

The table below is a compact way to think about where a commutator resurfacer makes sense, using the roughness and geometry numbers that show up again and again in maintenance documents.

| Situation on the machine | Primary method to reach for | Typical role of a commutator resurfacer | Practical roughness band after work (Ra, μm) | Downtime profile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surface film uneven, colour patchy, light banding, no serious step between bars | Guided or hand resurfacer with fine or medium stone, then silicon-carbide cloth | Main tool; restore texture and remove light defects without changing diameter | About 0.9–1.8 μm for industrial machines; 0.5–1.0 μm for small motors | One planned stop, rotor stays in frame |

| Brushes sparking on a few bars, measurable 0.02–0.03 mm step between adjacent segments, TIR still acceptable | Fixed-stone or portable resurfacer mounted on brush rigging | Main tool for local correction along full circumference; lathe not yet necessary | Similar 0.9–1.8 μm range, with care to avoid over-smoothing | Single outage, often within normal maintenance window |

| Heavy flats, severe grooves, obvious out-of-round, undercut almost gone | Lathe turning with diamond or carbide, then recessing, then cloth finish | Only for post-turning texture adjustment and controlled roughening after too-smooth diamond finish | After turning, adjust toward 0.9–1.8 μm with stone or cloth | Extended outage, rotor removed or machine opened up deeply |

| Surface glassy, film thick but geometry still good, low brush current issues | Medium-grade grinding stone on running commutator | Resurfacer replaces loose stone; easier to control pressure and radius | Bring roughness back above about 0.4 μm | Short, often done during routine inspection |

| Contamination, light pitting, but IR and bar step remain acceptable | Brush-based cleaning or non-conductive abrasives designed for commutators | Resurfacer used sparingly, mainly for localised defects | Within normal bands; avoid aggressive stock removal | Very short stop; focus is on cleanliness, not reshaping |

Values here are not tight tolerances; they simply reflect the roughness ranges and qualitative advice from industry guides and roughness charts. The point is: a resurfacer belongs in the same decision table as the lathe and the grinder, not in the “miscellaneous hand tool” drawer.

Stone grade and bond: what actually matters on the tool tip

Commercial commutator resurfacers ship with specific stone combinations for a reason. Martindale’s catalog describes non-dusting, fine-grain abrasives in polish and finish grades on a non-conductive bent handle; Ideal’s units come in medium, polish and finish variants with dimensions tuned for the machines they will see.

Behind the marketing, you can think in three simple stages. First, a medium stone to knock down ridges, break glazing and push the surface back into a functional roughness band without chasing every micron of runout. Second, a finer stone or pad to remove the coarsest peaks from that first pass, still leaving a clear pattern that brushes can track. Third, silicon-carbide cloth or equivalent fine abrasive for the final finish if the technical guide demands it. Morgan explicitly recommends 150–200 grit silicon-carbide as a standard final finish after turning and recessing, with emery reserved for specific cleanup work if at all.

Mersen’s roughness note ties that together by warning that if the surface drops below about 0.4 μm Ra in service, you should deliberately roughen it again with a medium grinding stone to restore enough peaks per centimetre, targeting something like 100 peaks per centimetre in practice. That is exactly what the “finish” side of a resurfacer does when used with discipline instead of habit.

Abrasive choice: the emery trap and conductive grit

Several repair notes from EASA and others repeat the same warning: aluminum-oxide emery cloth is a bad idea on commutators and slip rings because conductive fragments can lodge in the surface and promote arcing and damage. Yet emery is still what shows up in a lot of tool bags.

If you are using a commutator resurfacer with replaceable stones, that warning becomes easier to follow. You choose non-conductive abrasive stones designed for copper and carbon systems instead of generic shop abrasives. For loose cloth, silicon-carbide or garnet-based products are the usual recommendations, and the better guides say to wrap at least 150 degrees of the commutator and avoid finger pressure that rounds the segment edges.

In practice, that means your resurfacer kit should be boring: purpose-made stones, no home-made blocks with whatever abrasive happened to be available, no knife-sharpening stones of unknown composition. You already knew that intellectually; the resurfacer only makes it enforceable.

A resurfacing session, realistically

Imagine a machine that has been running for years. Film colour is uneven. There is light axial banding, but no clear evidence of massive step between bars, and insulation tests are fine. You do not want to pull the rotor unless you have to.

The sequence with a proper resurfacer looks something like this. First, you verify that the commutator is structurally stable: no loose bars, no obvious mechanical damage, undercut depth still there. Morgan’s guide is blunt on this point: check mica recess before any turning or grinding that could erase it, and never decide purely from skin colour that the commutator “needs” machining.

Next, you mount the resurfacer on the brush rigging or equivalent support so the stone tracks squarely across the face at running speed. The mounting is where many people cut corners. The stone should sweep a consistent path, with a controlled trailing angle if the manufacturer specifies one; some roughness documents even recommend that the grinding stone runs with a trailing orientation to keep the cutting action stable.

You start with a medium-grade stone. Contact pressure is light. The stone should cover a meaningful arc of the commutator, not just a few bars, so arc length and radius matter more than intuition admits. A few passes are enough; this is not rough turning. Between passes, you blow out copper dust and carbon debris instead of letting them embed.

Then you switch to the finer stone or polish pad. The goal is not to erase every mark but to leave a uniform, fine-textured surface. If diamond turning or heavy grinding was done previously and produced a surface that looks almost like a mirror, this is where you deliberately “spoil” that perfection to bring roughness back into the working band Morgan and Mersen describe.

After that, you inspect the mica recesses. Any copper smeared into the slots gets removed with suitable tools; Morgan even suggests a short hacksaw segment in a handle and small scrapers, with depth kept below slot width and sharp edges bevelled about half a millimetre at forty-five degrees. Only once the slots are clean and edges are chamfered do you consider the surface ready for service.

Finally, you clean aggressively. Copper dust, carbon dust, abrasive grains: all of it needs to leave the machine. The better guides talk about brushing and vacuuming the armature and field system after any resurfacing or turning work. Skipping that step is one of those quiet failure modes that show up months later as mysterious tracking or flashover.

Common traps when using commutator resurfacers

A few mistakes repeat across different industries and documents. EASA points out that many technicians rely on abrasive cloth or stones in situations where the underlying problem is loading or brush grade, so the surface gets cleaned but commutation does not really improve. The resurfacer exposes the same trap: if the machine is suffering from poor magnetic balance, defective interpoles, or unsuitable brush material, no amount of resurfacing will stabilise the arc.

Morgan warn against using handstones on a machine in normal running as a routine fix, noting that this is bad for brush life. A guided resurfacer is less harsh, but the principle holds: you plan resurfacing; you do not wave the tool at every spark you see. If you find yourself reaching for the resurfacer every outage, your inspection interval, brush selection or cooling strategy probably needs more attention than the copper.

Another regular trap is running the surface too smooth after a major turning job. Diamond tooling at high surface speed produces a visually perfect finish, yet both Morgan and Trade Engineering insist that this is not a suitable working surface for brushes, so a separate abrasive step is mandatory. A resurfacer with the right stone is the least painful way to perform that “controlled damage” step on the machine.

And then there is life-cycle thinking. Aerospacemanufacturing notes that with proper commutator care, you should expect a working life of ten to more than twenty years from the commutator. If you are chewing through that in half the time, there is a good chance that resurfacing is happening too often, too aggressively, or without enough respect for roughness limits.

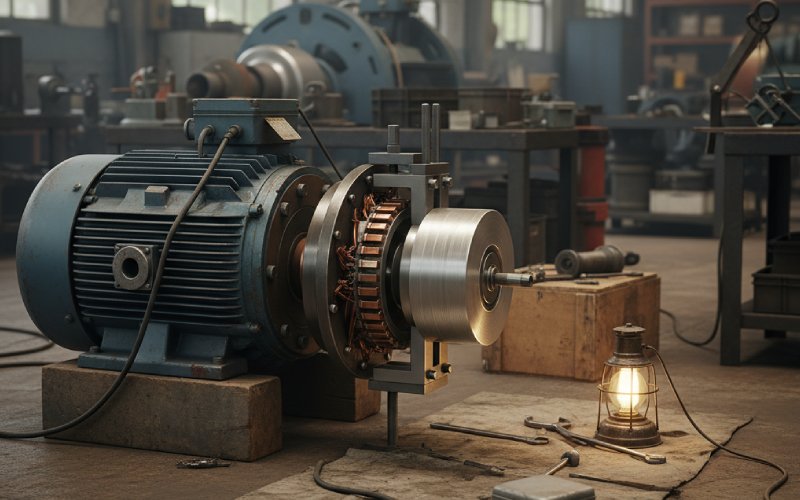

Using a resurfacer as part of a maintenance strategy, not an emergency fix

The real strength of a commutator resurfacer is not speed. It is that you can correct specific surface defects while the rotor stays in the frame, at full speed, in its own bearings. That means you are resurfacing under the same mechanical conditions the brushes see every day, instead of on a lathe with different supports and different distortion.

So you put it into your maintenance plan like any other machining process. Periodic inspection with clear geometric limits: maximum acceptable step between adjacent bars, minimum mica recess, roughness limits, acceptable film variation, maximum number of resurfacing operations before a full turn is mandated. The resurfacer then becomes the routine tool for keeping surfaces inside that box between over-smooth and over-rough. Lathe work remains reserved for when geometry has actually moved.

Bottom line: a commutator resurfacer is a small, specialized machining system that lives in the grey zone between “leave it alone” and “pull the rotor.” Used with real numbers in mind – roughness bands, segment step limits, abrasive selection – it quietly extends commutator life and reduces brush trouble. Used as a random abrasive stick, it just moves copper dust around and shortens the time until you are facing a full rewind.