Commutator Repair Tools: What Actually Matters In The Shop

Most commutator problems are not mysterious. They are the direct result of using the wrong tools, or using the right tools in ways that the catalog never warned you about. If you match your tool set to your actual failure modes, you stop “saving” bad commutators and start extending armature life on purpose instead of by accident.

Table of Contents

The quiet rule: tools follow failure modes, not brochures

You already know the theory: concentricity, film, mica depth, brush pressure, pollution, duty cycle. The trouble is that real machines reach your bench with a mix of issues, and the tool you grab first usually reflects habit, not diagnosis.

Most formal documents describe “turn, undercut, stone, clean, reassemble” as if it were a linear recipe. In practice it is more of a loop. You cut, you stone, you inspect, and every step slightly changes the one before it. The shop that treats commutator repair tools as a fixed kit usually burns more copper than necessary. The shop that treats tools as ways to control specific variables—roughness, bar profile, slot geometry, contamination—gets quieter brushes and fewer returns.

So this is not a list of products. It is a way to think about four things your tools must control: geometry, surface condition, dielectric gaps, and cleanliness. The catalog names are secondary.

Tool families you really work with

You can describe almost any commutator repair setup in terms of a few tool families: turning gear, undercutting gear, surface conditioning materials, and inspection or cleaning aids. Manufacturer guides and handbooks line them up differently, but the pattern keeps repeating.

Here is a compact way to look at them.

| Tool family | Typical tools in the wild | Main variable it controls | How it quietly creates new problems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Turning and truing | Engine lathe tools with carbide or synthetic diamond tips, small commutator lathes, portable turning tools that clip to the frame | This family restores concentricity and removes gross defects when runout or bar height spread is outside tolerance. | Overuse removes copper to mask electrical faults, thins bars unnecessarily, and can erase undercuts so deeply that you have to push mica removal harder than planned. |

| Undercutting and slot finishing | Flexible shaft or portable saw-type undercutters, bench mica undercutting machines, hand slotters made from hacksaw blades or commercial slotting files | These tools set slot depth, shape, and cleanliness so brushes never ride on mica and arc on raised or smeared edges. | Excess aggression leaves burrs, off-centre slots, or torn mica; shallow work gives “high mica” that shows up later as brush noise and streaking. |

| Surface conditioning | Single and double-handle grinding stones in coarse through polishing grades, commutator polishing stones, silicon carbide or garnet strips | This group sets surface roughness and helps build a stable brush film after machining. | Using the wrong abrasive or grit contaminates the film, rounds bar edges, or leaves the surface too smooth, so the film never stabilizes and sparking follows. |

| Cleaning and inspection | Dial indicators and TIR gauges, slot depth gauges, stiff fibre brushes, insulated vacuums, stroboscopes, magnifiers | These tools reveal what the others actually did and clear out conductive dust and copper debris before restart. | Skipping this family means working blind; debris left in slots and around brushgear gives you arcing that gets blamed on “stone quality” or “bad brushes.” |

Once you view your bench this way, gaps in your kit become obvious. So do the tools that are only there because someone liked the feel of a particular handle thirty years ago.

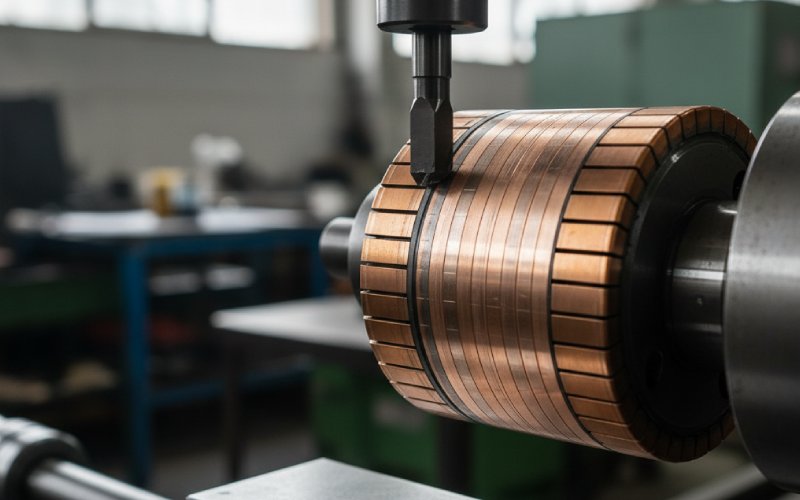

Turning tools: cutting copper without cutting life

Formal texts say it plainly: if the commutator is seriously out of round, the preferred fix is to turn it on a machine lathe and follow with stones; local stoning alone is a second-best, “get it back on the line” move. You probably follow that already, at least when there is time.

The more useful question is how hard you push the turning tools. If you expect the lathe to solve electrical problems, you will keep cutting until the mechanical trace looks beautiful while the root cause—wrong brush grade, bad ventilation, high mica—remains untouched. The result looks good under a strobe and then comes back with bar burning and heavy dust after a few weeks.

Synthetic diamond tools and high-quality carbides tempt you to skim “just a hair more” because they cut so cleanly, especially on tough copper alloys. Catalogs highlight that smooth finish and long tool life. The quiet rule to keep in the back of your mind is simple: minimum metal removal consistent with correcting TIR and defects. When you stop as soon as indicator readings and visual checks justify it, stones and film will finish what the tool bit started.

Portable turning fixtures are another compromise. They save dismantling time on some machines and keep you competitive on quick-turn jobs. But the more portable the setup, the more you depend on the operator’s touch for feed, depth, and alignment. The risk is that you chase local flats and grooves and forget that the commutator wants to be a cylinder, not a series of patches.

So you treat turning tools as rough geometry setters, not as polishing tools and not as your primary way of “making it look better.”

Undercutting tools: where most of the subtle damage happens

Mica undercutting is described in handbooks in a very calm way: remove mica below bar level, keep depth in a certain range depending on bar width, avoid contact between mica and brushes. The procedure sounds simple until you look closely at what actually comes out of the slot.

Flexible shaft, saw-type undercutters are still the preferred approach when you want to avoid pulling the armature out of the machine. Only the brush rigging needs to move, and you saw along the slots while the rotor stays on its own bearings. Bench undercutting machines with adjustable V-blocks and traversing saws become attractive once you have a steady flow of armatures and space for fixtures. Both are efficient. Both can do serious harm if you treat them like regular metal-cutting saws.

Manufacturer notes on undercutting wheels quietly remind you that mica behaves more like a mix of crushing, grinding, and chip conveying than clean shearing, which is why the saw design is special and the tooth form and bond matter. That also means feed pressure and coolant temptation must be controlled. Lubricant in the slot changes chip formation, clogs the slot, and goes exactly where you do not want it. Practical guides tell you straight: never use lubricant when cutting mica and always clean out loose pieces before energizing the machine.

Hand tools sit on the other end of the scale. Many shops still shape hacksaw blades into slotters, grind off the teeth where they might touch copper, wrap tape or fit a handle, and cut by hand. Others buy purpose-made slotting files and V/U profile scrapers. These are slower, but they give you more tactile feedback and less risk of off-centre cuts on small commutators.

The silent killer in this whole family is burrs. Any power undercutter will leave a lip on bar edges unless you chamfer properly. Technical guides recommend beveling edges after undercutting, often with small scrapers or files shaped to V forms, to help the brush glide from bar to bar. If you skip or rush that step, you “fix” high mica and then immediately create a bar-edge arc trigger.

So a mature toolkit has both sides: power undercutters for throughput, and fine hand tools for correction, edge dressing, and fixing the mistakes that the motorized tools happily introduce.

Stones, strips, and the real control of surface roughness

Stones and flexible abrasives are where theory, catalogs, and habits collide. Stone catalogs split products into coarse, medium, fine, and polishing grades, sometimes with multiple grade letters, and they are not doing this for fun. Each grade is tuned either for metal removal, roughness control, or film management on commutators and rings.

Coarse grades remove copper quickly and are useful for high mica, pitted surfaces, or ridges that remain after turning. Medium grades are intended for general finishing and for achieving the roughness that supports a stable graphite film from the brushes. Fine and polishing grades sit at the other extreme, focusing on cleaning and light finishing when geometry is already correct.

Two traps show up repeatedly in service reports and technical notes. The first is abrasive type. Industry resources now clearly warn against using emery cloth with aluminum oxide on commutators, because conductive abrasive particles can embed, promote arcing, and damage the surface. Garnet paper or dedicated stones are preferred when you must use flexible abrasives. The second trap is over-smoothing: very fine finishes feel satisfying, but several guides suggest that the best surface is not mirror-like; it has a controlled roughness that lets brushes build a uniform film.

That is why catalog sections on silicon carbide cloth and bedding stones keep emphasizing grade selection and technique. If you stone in the wrong direction relative to rotation, press on one side, or rock the stone, you produce rounded bar tops and uneven wear patterns that show up later as banding on the brush face.

So the question when you reach for a stone should not be “What is on the bench?” It should be “What roughness and film behaviour do I want, given the brush grade and duty of this machine?” Once you phrase it that way, the usual “medium stone for everything” habit looks less convincing.

Cleaning and inspection: the tools that decide whether the repair sticks

Cleaning tools rarely get respect. They are cheap, not very shiny, and no one takes a photo of a fibre brush or vacuum hose for the website. Yet the official guides keep repeating the same warning: after machining, undercutting, and bevelling, any copper debris and dust in slots and around the armature and field must be removed thoroughly by brushing and vacuuming. If you skip that, all the nice work on geometry and roughness has to fight conductive debris in the worst possible places.

Dial indicators and TIR gauges are similar. You could do repairs by feel and by brush imprint, but once you start logging TIR and bar-to-bar height variation before and after each job, your tool choice becomes more disciplined. Heavy turning decisions become traceable. Quick stone cleanups and “good enough” jobs stop hiding behind vague language.

There are also newer additions that older manuals barely mention. Digital stroboscopes make it easier to see sparking patterns and commutator film behaviour on running machines. Maintenance tool cases from some suppliers now bundle stones, slotters, and undercutting accessories into standardized sets so that every technician has a consistent baseline kit. None of this replaces judgment. It just removes excuses.

Single-purpose tools versus universal commutator machines

A lot of official documentation assumes a shop built around separate machines: lathes, undercutters, drill presses, winders. That is still common, especially in small and medium shops. Recently, though, equipment makers have pushed universal commutator repair machines that combine turning, automatic undercutting, deburring, and sometimes banding and welding into one programmable unit.

These machines reduce armature handling and cycle time by keeping the workpiece in one setup for multiple operations. They add things your older tools never had: stored recipes for different armatures, programmable carriage feeds, automatic indexing, fibre-optic mica slot sensors, and dedicated brush deburring attachments that replace tedious hand chamfering with a repeatable motion. For shops handling medium to large traction and mill motors, this is not a gadget; it is a way to keep quality consistent even as staff rotates and volume grows.

The trade-off is subtle. When you centralize too much capability in one machine, you risk building your process around whatever that machine is good at. If its undercutting head prefers a certain slot profile, you may slowly drift all jobs toward that profile, even when particular machines might like different slot geometries or depths. So the mental rule can be: use universal machines to make good practice easier to repeat at scale, not as a reason to forget why each operation exists.

A healthy shop keeps some sharp hand tools and stand-alone fixtures alive alongside the fancy machine. Not out of nostalgia. Because there will always be an odd armature, a critical rush job, or a repair on a machine too big or too small for the main line, where that old slotter or small lathe still does the right thing.

Building a serious, compact commutator repair kit

If you stripped your bench down to essentials, you would still want one turning method you trust, one undercutting method with capacity for your usual bar sizes, a small but complete family of stones, and solid cleaning and measurement tools. Everything else is refinement.

So you might pair a general-purpose lathe or commutator turning rig with a flexible shaft undercutter, then back them up with a set of hand slotters and scrapers for corrections and small units. Stones would span at least three levels—coarse, medium, and finishing or polishing—matched to your most common machine sizes and copper hardness, plus a few shaped or pencil stones for tight spaces. For cleaning and inspection, you would standardize on non-conductive brushes, vacuums rated for fine dust, basic dial indicators, and a simple way to record TIR and slot depth for every job.

That kit is not glamorous. It is just enough to control the variables that actually decide whether the motor runs quietly six months from now. The deeper, more specialized tools—automatic multilayer undercutters, universal machines, advanced stroboscopes—layer on top of that, not instead of it.

Closing notes

Good commutator repair is not about having the largest tool catalog on the wall. It is about making each tool in your shop responsible for a clearly defined variable and refusing to let it “help” outside that role.

Turning gear manages geometry. Undercutting gear manages dielectric gaps and slot shape. Stones manage roughness and film. Cleaning and inspection gear tell you what really changed. Everything else is detail.

Once you start viewing commutator repair tools through that lens, you stop asking which stone or which undercutter is “best.” You start asking whether your current kit lets you fix the failures you actually see, with the least copper removal and the most repeatable results. That is the point where your tool cart stops being an accident of history and starts being part of your reliability strategy.