Commutator Profiler: The Quiet Little Tool That Saves Very Big Machines

If you work around DC motors or slip-ring machines long enough, you learn one thing fast: the commutator has moods.

Some days it runs quiet and clean, brushes sitting happily on a smooth copper surface. Other days, it feels like the whole motor is complaining — arcing, vibration, unexplained heat, brush dust everywhere. And yet from the outside, the machine “looks fine.”

That’s where a commutator profiler stops being a nice-to-have and becomes your best friend. It doesn’t just give you numbers; it gives you a story about what’s happening at the brush track, bar by bar, millimetre by millimetre — long before you have a failure on your hands. Tools like CL-Profiler, MMS7000, ComPro2000 and similar instruments were designed exactly for this purpose: to map run-out, bar-to-bar height and ovality with micrometre-level resolution on live machines.

In this guide, we’ll go deeper than the usual spec sheet and marketing brochure, and actually talk about how a commutator profiler fits into real maintenance life, how it works, and what “good” looks like when you’re choosing or using one.

Table of Contents

What a Commutator Profiler Actually Does

- Reads the surface like Braille: A contact or non-contact sensor is moved around the commutator or slip ring to “feel” every rise and dip in the surface.

- Turns height changes into data: Those tiny height variations — often on the order of 1 µm (0.04 mil) — are converted into digital signals for analysis.

- Builds a profile of the rotor: The device reconstructs the surface as a graph or radial plot, showing ovality, run-out, and bar-to-bar height differences.

- Highlights developing defects: Patterns like a “lumpy” profile, repeating peaks, or high bars point to mechanical distortion, thermal growth, poor brush contact or contamination.

- Feeds your reliability program: Profiles can be trended over time, layered with other data (current, temperature, vibration) and turned into early maintenance decisions rather than late emergency repairs.

Why Commutator Wear Is Really a Profit Problem

When you strip away the jargon, commutator wear is not just a surface problem — it’s a money problem hiding in your copper.

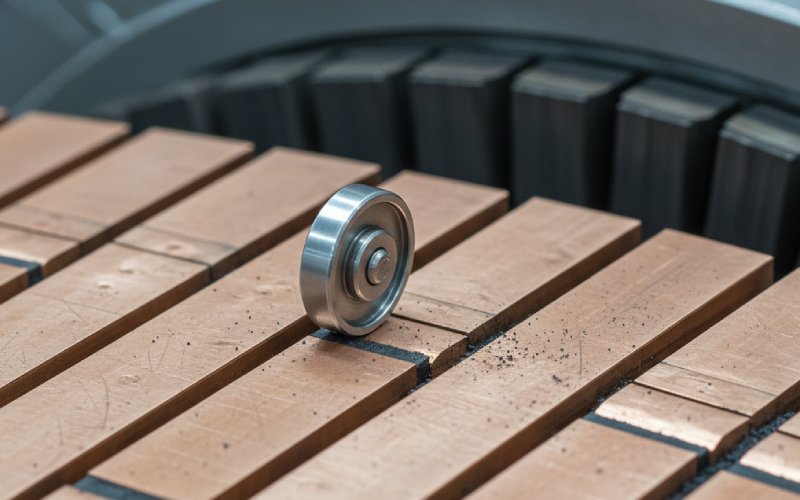

Over time, your commutator is attacked from two sides: mechanically by the brushes and electrically by current transfer. Uneven wear leads to ovality and bar-to-bar height variations. That creates unstable brush contact, more arcing, more heat, and more carbon dust. It’s a self-reinforcing spiral.

Traditional visual checks and occasional machining can catch obvious damage, but they’re blind to subtle shape changes that have already started to hurt performance. You might be losing efficiency, burning brushes faster than necessary and running closer to a flashover than you realise — all while your reports just show “motor still running.”

This is exactly why modern profilers exist. Devices like CL-Profiler and MMS7000 are explicitly sold around the idea of keeping commutators and slip rings within tight ovality and run-out limits, often with about 1 µm resolution and clear visualisation tools.

With a profiler, you stop arguing about opinions (“that looks fine”) and start managing facts (“ovality has increased 30% in the last 12 months; we’ll be out of tolerance in another two outages if we do nothing”).

Early Warning Signs a Profiler Could Have Caught Sooner

- Brush life suddenly drops: You’re changing brushes far earlier than expected, even though current and load haven’t changed much.

- Arcing that appears “only sometimes”: Sparking shows up at certain speeds or load conditions, making it hard to pin down.

- Banding on the commutator surface: You see darker and lighter bands around the circumference instead of an even track.

- Temperature creep: Frame or bearing temperatures keep rising slowly over months, with no obvious root cause.

- Noise during startups: A motor that used to start smoothly now “growls” or vibrates slightly when coming up to speed.

- Repeat issues after overhaul: You repair or resurface the commutator, and the same symptoms reappear sooner than they should.

- Frequent flashovers in one fleet: A certain group of machines has more commutation problems than the rest, even though they’re “identical.”

Each of these is often rooted in geometry issues — ovality, bar tilt, high bars — that a profiler can see clearly long before they show up as catastrophic events.

How a Commutator Profiler Works

At its heart, a commutator profiler is just a profilometer specialised for rotating electrical machines — instead of measuring the roughness of a random part, it measures the shape of your commutator or slip ring.

There are two main “personalities” of profiler you’ll meet:

- Contact profilers These use a small wheel or stylus pressed lightly on the surface. As the rotor turns, the sensor moves with it and measures height changes. CL-Profiler is a classic example: it uses an inductive probe with contact measurement and a hard, wear-resistant tip for “live” readings.

- Non-contact profilers These use technologies like eddy current displacement sensors. Mersen’s ComPro2000, for instance, uses a non-contact transducer to measure the commutator profile at any speed, under actual operating conditions, without being affected by voltage or temperature.

Modern systems like the MMS7000 Profiler combine a high-resolution sensor with an industrial handheld computer. You enter basic machine data (number of bars, circumference, machine type), rotate the rotor or run the machine, and the profiler continuously samples displacement — typically every fraction of a millimetre — to build a detailed picture of the surface.

Some profilers go further and also log:

- DC current through the armature

- Temperature at the brush-commutator interface

This is what instruments like the original Commtest Profiler were designed for, letting you analyse not only shape but also operating conditions in a single test.

All that data is then visualised as:

- Linear profile plots (height vs distance)

- Radial plots (showing ovality as a “bulged” circle)

- Bar-to-bar height charts

- Alarm thresholds and tolerances

You get a view that’s far richer than “looks OK” or “looks bad” — you see how and where it’s going bad.

Key Features to Look For When Choosing a Commutator Profiler

- Resolution and accuracy

- Aim for around 1 µm resolution. This has become the practical benchmark in modern profilers like CL-Profiler and MMS7000.

- Contact vs non-contact capability

- Contact is usually fine for low-speed or offline checks; non-contact is ideal for measuring at operating speed or when you can’t safely touch the surface.

- Static and dynamic profiling

- Static: rotor stopped or slowly rotated by hand.

- Dynamic: motor under real load and speed. Non-contact solutions excel here.

- Support for both commutators and slip rings

- Look for a mode or probe that handles both segmented surfaces (commutators) and continuous rings. MMS6000/MMS7000 style systems explicitly support both.

- Bar-aware analysis

- The ability to enter number of bars and view bar-to-bar height differences, including max bar-to-bar (MBTB) and similar metrics.

- Data handling & software

- Can you trend results over time? Export to your CMMS? Overlay multiple profiles? Tools like EVOsoft (for MMS7000) or vendor-provided PC software are designed for exactly this.

- Ruggedness and usability

- Field work is not kind to electronics. A profiler that lives in a padded case but dies in a dusty, hot machine room is not helping you. Look for handheld devices rated for industrial use, with touchscreens you can operate with gloves.

- Training & support

- The best systems come with clear quick-start guides, reference manuals, and vendor training. This matters as much as hardware when you’re trying to embed the tool into your maintenance routines.

Comparing Your Options: Manual vs Modern Profilers

Below is a simplified comparison of typical approaches you’ll see in the wild. It’s not a brand shoot-out, but a way to think clearly about where you are today versus where you might want to go.

| Approach / Example | Measurement Type | Typical Resolution | Data Captured | Downtime Needed | Best For |

| Dial gauge & straight edge (manual) | Contact, point-based | ~10–50 µm (operator-limited) | A few points, no full profile | Machine stopped | Rough checks, small shops |

| Contact profiler (e.g. CL-Profiler) | Contact, inductive | ~±1 µm | Full run-out, ovality, bar profile | Usually slow or stopped rotor | Field profiling, acceptance tests |

| Portable profiler (e.g. MMS7000) | Contact wheel sensor | ~1 µm, bar-aware | Commutator & slip ring surface, MBTB | Slow rotation or low speed | Routine condition monitoring |

| Non-contact high-speed (e.g. ComPro2000) | Non-contact, eddy current | High resolution at any speed | Static + dynamic profiles under load | Minimal / none (online) | High-criticality machines, dynamic issues |

| Integrated profiler + current & temp (e.g. Commtest Profiler style) | Usually contact | Micrometre-class | Profile + DC current + temperature | Depends on setup | Root-cause studies, deep reliability analysis |

The real win is not just “better numbers” — it’s the ability to trend those numbers over time and correlate shape changes with operating conditions. That’s how you go from firefighting to foresight.

A Practical Workflow for Using a Commutator Profiler in the Field

- 1. Decide the purpose of the measurement

- Is this baseline data on a new machine? A follow-up after repair? A troubleshooting measurement for a problem machine?

- 2. Collect nameplate and basic geometry

- Machine type (commutator vs slip ring), number of bars, rotor diameter/circumference, speed range, typical load.

- 3. Prepare the machine and environment

- Ensure guards are removed safely, tagout/lockout is followed if needed, and you have enough access to mount the probe or wheel.

- 4. Mount the sensor correctly

- For contact systems, usually in a brush holder with spacers; for non-contact, at the specified stand-off distance with a stable fixture.

- 5. Choose static or dynamic profiling

- Static: slowly rotate the rotor one full revolution.

- Dynamic: run the motor at operating speed, staying within the profiler’s rated limits.

- 6. Capture and review the first profile on-site

- Check for obvious issues: large ovality, high bars, repeating patterns. If needed, re-measure to verify.

- 7. Store, tag and trend the data

- Give the profile a meaningful name (machine ID, date, speed, load), store it in the vendor software or your CMMS, and create a simple traffic-light rule (green/amber/red) for future comparisons.

Over time, this workflow becomes as normal as vibration routes or infrared scans — it’s just “how we look after commutators here.”

Common Mistakes When Using a Commutator Profiler (And How to Avoid Them)

- Treating it like a one-off test, not a trending tool

- Fix: Always compare today’s profile to older ones; change over time is more important than one absolute value.

- Ignoring bar-to-bar information

- Fix: Use bar-aware modes and MBTB metrics where available; many commutation issues come from a small number of bad bars, not the whole surface.

- Poor sensor mounting

- Fix: Spend the extra minute packing the sensor correctly in the brush holder or bracket; loose mounting gives noisy, misleading data.

- Not recording operating conditions

- Fix: Log speed, load, current and temperature where possible (some profilers do this natively); a surface that looks bad only at certain load points tells a very specific story.

- Skipping training

- Fix: Use the vendor’s quick-start guides, manuals, and training. Tools like MMS7000 and CL-Profiler ship with detailed instructions for measurement and data transfer — use them.

- Letting the data live only on one laptop

- Fix: Centralise profiles and back them up; make them part of your broader asset condition history, not just “Bob’s profiler files.”

Bringing It All Together

A commutator profiler may look like a niche gadget, but in a plant where DC machines still matter, it’s one of the few tools that can literally show you the shape of future failures — and give you enough lead time to do something about them.

The most advanced devices on the market today combine:

- Micrometre-level resolution

- Support for both commutators and slip rings

- Static and dynamic profiling

- Rugged, handheld hardware plus rich analysis software

- The ability to trend and correlate with current, temperature and other signals

But the real differentiator isn’t just the hardware; it’s how human your use of it is:

- Are you using it to tell a clear story to operations and management?

- Are you turning profiles into simple limits and routines your team can own?

- Are you learning the “normal” fingerprint of each machine, so you can spot when one starts to drift?

If you can answer “yes” to those questions, you’re already ahead of most competitors who just skim the datasheet and move on.

In the end, a commutator profiler is a conversation tool between you and your machines. The more you listen, the less they surprise you. And in maintenance, “no surprises” is about as close as you get to peace.