The Hidden Aerodynamics of the Commutator Interface

Commutation in small DC motors is rarely a simple mechanical switching event; it is a chaotic, plasma-driven limit on flight performance that dictates the responsiveness of your drone more than the battery’s C-rating. If you are still treating your brushed motors as static components that merely conduct electricity, you are ignoring the dynamic braking forces and inductive spikes that actively fight your flight controller’s PID loop during every throttle punch.

Table of Contents

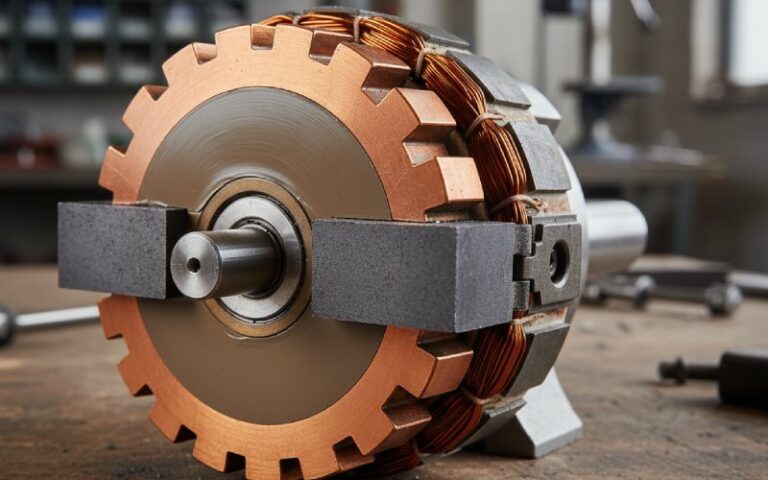

The Inductive Kick and Plasma Erosion

We often conceptualize the brush-commutator interface as a sliding electrical contact, but at 30,000 RPM, it functions more like a controlled spark gap. As the commutator segment leaves the brush, the collapsing magnetic field in the armature coil generates a flyback voltage spike. In larger industrial motors, interpoles manage this. In your Micro Brushed motor, there are no interpoles. The energy has nowhere to go but to arc across the trailing edge of the brush. This isn’t just “inefficiency”; it is a localized plasma event that vaporizes copper.

When you punch the throttle on a micro-drone, the current density skyrockets, and the inductive kick becomes violent. This arcing doesn’t just eat the brush; it roughens the commutator surface, creating a feedback loop. A rougher surface bounces the brush. Bouncing breaks electrical contact for microseconds. The flight controller sees this as a loss of thrust and compensates by driving the PWM signal higher, which in turn increases the current and the violence of the arcing. You aren’t just wearing out a motor; you are creating high-frequency noise that desynchronizes the physical thrust from the flight controller’s commands.

The Invisible Brake: Neutral Plane Shift

Most hobbyists understand timing advance—rotating the endbell to fire the coils early—but few consider the devastating effect of the “neutral plane shift” during deceleration. When you chop the throttle to dive or corner, the motor becomes a generator. The armature reaction—the magnetic field distortion caused by current flowing in the rotor—drags the neutral electrical plane backward.

If you have aggressively advanced your timing for forward speed (common in racing setups), you have inadvertently optimized the motor to resist deceleration. The brushes are now effectively shorting coil segments at the wrong point in the magnetic wave during braking events. This creates massive drag and heat, not efficient regenerative braking. The motor fights its own momentum. The heat generated here is often misdiagnosed as “over-gearing,” but it is actually a geometric misalignment between your brushes and the distorted magnetic field during transient load changes.

Chemical Filming and Material Migration

Copper drag is the silent killer of high-performance micro motors. Under heavy load and heat, the copper surface of the commutator softens. The friction from the brush doesn’t just wear it down; it smears the copper across the insulating gaps between segments. Once this conductive smear bridges the gap, you have a hard short. The motor doesn’t stop working immediately. Instead, it loses a fraction of its torque, the kv rating effectively shifts, and your battery life inexplicably drops.

This material migration is accelerated by the “patina” misconception. While a chocolate-brown film is desirable in industrial motors running steady loads, the erratic, violent throttle changes of an RC pilot prevent stable film formation. You are constantly stripping and rebuilding this oxide layer. In high-performance hobby applications, you are often running on raw, unoxidized copper, which increases friction and the likelihood of adhesive wear (threading).

Diagnosing Flight Behavior via Commutator Pathology

You can read your flying style on the surface of the commutator. The physical appearance of the metal segments correlates directly to specific inefficiencies in your setup or piloting habits.

| Commutator Symptom | Physical Cause | Correlated Flight/Drive Behavior |

|---|---|---|

| Pitch Bar Burning | Uneven periodic arcing on specific segments. | The pilot experiences a “stutter” or desync feeling at specific RPM bands, often mistaken for a bad gyro tune. |

| Grooving (Phonographing) | Abrasive wear cutting distinct channels. | Typically caused by dust ingestion, but often indicates the pilot is flying in gritty environments without intake protection, leading to erratic low-throttle resolution. |

| Bar Edge Burning (Trailing) | Late commutation causing arcs on the exit. | The motor timing is too neutral for the speed being attempted. The drone feels sluggish at top end, lacking “pop” in punch-outs. |

| Copper Drag (Smearing) | Overheating causing metal to flow into slots. | Excessive braking or frequent “chop and punch” maneuvers. The drone loses top speed over the session as partial shorts form. |

| Bright Threading | Metal transfer from commutator to brush. | Spring tension is too low for the vibration levels. The drone sounds “rough” or “screamy” during high-g turns due to brush float. |

The False Economy of Longevity

We obsess over making motors last, yet in competitive environments, a motor that lasts forever is likely under-performing. The commutator is a consumable friction surface. If you aren’t seeing signs of thermal stress or arcing, you aren’t utilizing the full magnetic potential of the stator. There is a perverse optimal point where the commutator is degrading at exactly the rate required to sustain maximum current throughput. Stop trying to keep them pristine. Accept that the commutator is a fuse that burns to buy you performance.