How Commutator Technology Competes in an Increasingly Brushless World

Commutators aren’t “winning” the way they did. They’re still competing because they keep solving a few problems that brushless systems, for all their upside, sometimes create.

Table of Contents

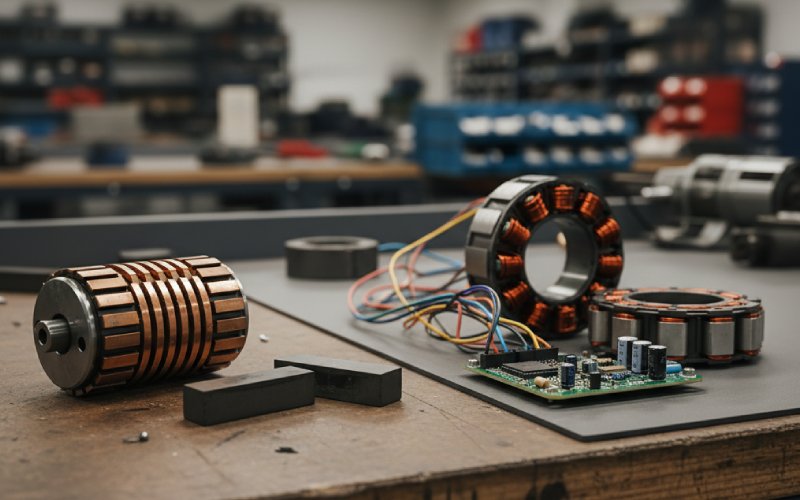

Brushless didn’t replace a motor, it replaced a failure budget

Most comparisons stop at efficiency, noise, and lifetime. Sure. Brushless motors generally run with less internal friction and no brush wear, so you tend to get higher efficiency and longer service life, plus better torque density and speed range in many designs.

But the practical replacement is bigger than “brushed vs brushless.” You’re trading a mechanical commutation problem for an electronics-and-software problem. That trade is often correct. It’s also not free. Driver choice, sensing strategy, commutation method, EMI behavior, thermal layout, connector decisions, firmware update paths, production test coverage—none of that exists when your commutation is copper segments and carbon. TI’s own commutation discussion makes the point indirectly: trapezoidal, sine, FOC all have different complexity and performance costs, and you pay that cost somewhere (compute, sensing, tuning, validation).

So the question isn’t “why would anyone still ship brushes?” It’s “what else would I have to ship with brushless, and can my product tolerate that?”

The places commutators keep their footing are not glamorous

Brushed motors remain competitive where the system wants to be blunt: apply voltage, get torque, stop thinking. Mechanical commutation is doing the coordination work inside the motor, not in your PCB, not in your codebase. That simplicity is repeatedly called out even by companies that like selling drivers and control ICs: brushed DC is simpler to drive and cheaper at the system level, especially when you don’t need tight closed-loop behavior.

And there’s a second, quieter advantage: tolerance for “messy power.” Cheap supplies, battery sag, contact resistance, dirty connectors, voltage spikes from long leads. A brushed motor can be forgiving because the control loop can be… absent. maxon even frames the baseline reality plainly: a brushed DC motor can run directly from a voltage source; brushless can’t.

That shows up in product categories people keep citing as “still brushed” for a reason: tools, appliances, low-cost actuators, stuff that is built to be replaced rather than optimized. Some of those markets are shifting fast, but the underlying constraint hasn’t changed: if the business model can’t afford the driver electronics and the validation work, brushes are still a rational choice.

Universal motors are basically the commutator’s last big stronghold (and they’re under pressure)

If you want a concrete example of commutator tech staying relevant because it matches a product’s shape, look at suction motors. TI notes the universal motor as a typical choice for vacuum cleaner suction across many designs. That’s not nostalgia; it’s an existence proof that commutators can still deliver high speed and usable power density in a brutally costed appliance.

But universal motors also illustrate the squeeze. When efficiency becomes a headline requirement instead of an engineering preference, the commutator starts paying a tax. A paper comparing a universal motor against a BLDC in a mixer-grinder context reports a wide efficiency gap (universal in the low-50% range versus BLDC around 80% in their setup). You can argue about operating points and implementation details. You can’t argue about the direction of the pressure.

So universal motors persist where the product can tolerate the losses (or where purchase price dominates), and they retreat where energy standards, battery runtime expectations, or thermal limits tighten.

“Efficiency” is sometimes just shorthand for “regulation and procurement policy”

In building HVAC and fan systems, brushless adoption is often driven by operational efficiency targets and the institutions enforcing them. Singapore’s NEA materials, for example, discuss electronically commutated (EC) motors as essentially brushless DC motors with higher operating efficiency than common low-power fan motors in certain applications.

This kind of document matters because it shapes purchasing rules and retrofits. Once procurement starts specifying EC motors for a class of fans, the commutator doesn’t get to compete on romance or repairability. It competes on exceptions: first cost, availability, interchangeability, installation constraints, or edge-case duty cycles.

That’s a theme. Brushless wins cleanly when the “system owner” pays the energy bill and can wait for ROI. Commutators hang on when the buyer’s incentives are shorter-term or fragmented.

EMI is not a brushless victory lap; it’s a different kind of mess

Brush arcing can be an EMI source, and everyone knows the usual suppression components and layout habits. You can make a brushed system pass compliance, but you spend effort and you accept some noise behavior.

Brushless removes the arcing, yes. Then it introduces high-frequency switching edges and a motor cable that behaves like an antenna when you’re not careful. Portescap’s EMC discussion is refreshingly direct: BLDC avoids brush-commutation arcing, but the driver’s fast switching produces conducted and radiated emissions if the design isn’t managed.

So “brushless is cleaner” is only true if the electronics are done well. And “brushed is dirty” is only true if you ignore suppression. In practice, both can be compliant, and both can fail compliance in very normal ways.

If you’re deciding between them, EMI is less about which one is morally better and more about which failure you’d rather debug: stochastic brush noise and suppression tuning, or switching harmonics, gate drive behavior, grounding strategy, and cable routing. Pick your headache. Not an emotional statement. Just resource planning.

A comparison table that matches how products actually get chosen

| Dimension that actually decides programs | Brush-commutated DC / Universal (commutator + brushes) | BLDC / EC (electronic commutation) |

|---|---|---|

| Upfront system cost | Often lower because control electronics can be minimal | Often higher due to inverter/driver, sensing or estimation, and validation |

| Control dependency | Can run from a voltage source; control optional | Controller required; commutation strategy is part of product definition |

| Maintenance / wear | Brushes wear; commutator wear exists; service may be simple if accessible | No brushes; electronics become the wear item (thermal, capacitors, solder, connectors) |

| Efficiency pressure | Can be acceptable in intermittent/low-duty use; struggles as standards tighten | Stronger position when energy or runtime is a requirement |

| EMI character | Brush arcing noise; suppression is well-known | Switching noise; layout, filtering, cable behavior matter |

| Best-fit use cases (typical) | Cost-driven, tolerant of noise, short duty, simple controls, field repair | Long duty, efficiency targets, low noise, higher performance control, compactness |

This table is unfair in one way: it treats electronics failures as a given in brushless systems. They are not inevitable. They’re just part of the design space. Same with brush wear. The point is that each approach has a dominant “risk bucket,” and programs get delayed when they pretend otherwise.

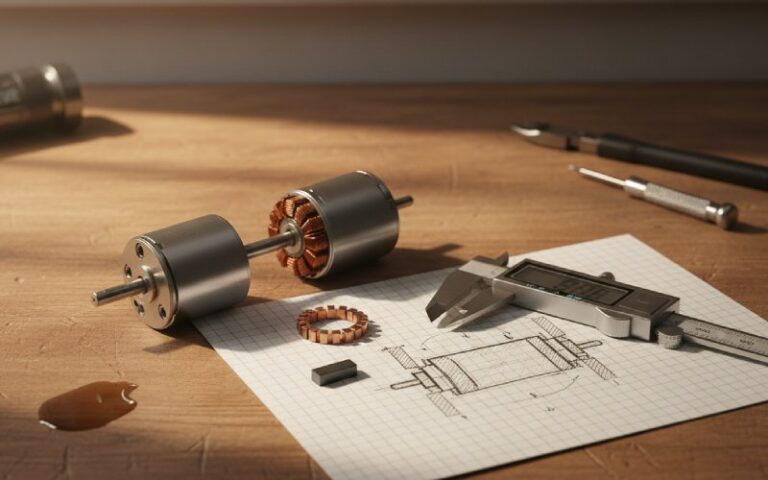

How commutator tech competes: by shrinking the gap where it matters, not everywhere

A brushed motor doesn’t have to be “dumb.” A lot of teams quietly modernize commutator systems with just enough electronics to remove the ugliest problems while keeping the cost model intact. PWM speed control, current limiting, soft-start, and basic thermal protection can shift user experience and reliability without turning the product into a control-software project. The brushed-motor driver discussions from component vendors basically exist because this is common and useful.

This is one of the commutator’s real competitive moves: selective modernization. You don’t chase field-oriented control. You chase “it doesn’t stall and burn,” “it doesn’t brown out the supply,” “it doesn’t spit too much noise into the line,” and “it doesn’t require a firmware team.”

There’s a mild contradiction here: adding electronics is what brushless already forces you to do. True. The difference is scope. A brushed motor can take a small dose of electronics and stop. Brushless can’t stop; commutation is the electronics.

The hidden advantage of commutators is organizational, not technical

This part rarely appears in comparison articles because it’s not a motor spec. It’s a company spec.

If your manufacturing line, supplier base, test equipment, field service network, and failure analysis habits are built around commutators, the motor is not just a component. It’s an ecosystem. Switching to brushless can be correct and still be expensive in ways the BOM doesn’t show: new incoming inspection regimes, new end-of-line tests that actually catch driver defects, new supplier audits for power devices, new root-cause loops for “intermittent reset at cold start” bugs that never existed before.

A brushed motor failure can be mechanical and visible. A brushless failure can be electrical and conditional. That doesn’t make it worse. It makes it different, and your organization may or may not be shaped for it.

So commutators compete partly by being already integrated into the company’s habits. That is not a romantic argument. It’s an accounting argument with engineering consequences.

Where commutators lose anyway, even when you want them to win

Battery-powered devices are a straight example. If runtime, heat, and size are top constraints, brushless tends to take the slot because efficiency and torque density translate directly into product behavior. That’s why cordless vacuums and similar categories talk so much about BLDC designs; the physics shows up as minutes of runtime and grams of battery.

Low acoustic noise requirements can also corner commutators, not because a brushed motor must be loud, but because brush contact and commutation artifacts are harder to fully erase than controlling current waveforms with electronics. Again, not a moral claim. Just a pattern that shows up when product requirements get strict.

And high-duty industrial use where maintenance windows are scarce tends to favor brushless for lifecycle reasons, because “replace brushes periodically” stops being cute when the motor is buried in a machine. The usual industrial framing reflects that: higher efficiency, less maintenance, longer life.

So what does “compete” mean in 2026?

It means commutator technology keeps winning the narrow contests it was built for: lowest-cost torque, low-friction adoption inside existing designs, and systems that don’t want a controller as a first-class product feature. Brushless keeps winning the contests modern requirements keep creating: efficiency mandates, runtime expectations, compactness, low maintenance, and controllability at scale.

The brushless world isn’t total. It’s segmented. Commutators survive by fitting the segments that still reward simplicity, and by borrowing just enough electronics to avoid their most predictable losses—without inheriting the entire brushless complexity stack. That’s not a comeback story. It’s a stable niche strategy.