Commutator Motor Types

If you already know the datasheets and the standards, the choice between commutator motor types reduces to three questions: what torque shape you need, how ugly your supply is, and how much brush maintenance you can live with. Everything else is mostly implementation detail and cost arguments around those three.

Table of Contents

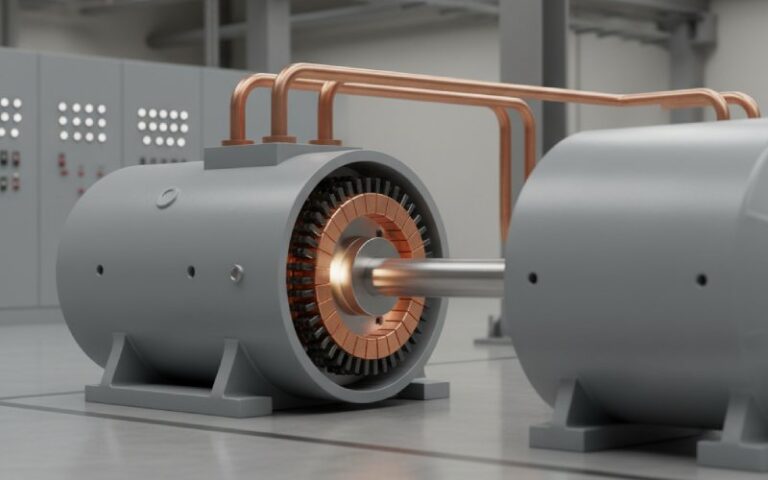

The real split: DC versus AC commutator motors

Most “commutator motor type” discussions get lost in the historic taxonomy. From a design or selection point of view, you can start much more brutally: is your commutator sitting in a DC machine, or are you forcing it to survive on AC as well.

On the DC side you see series, shunt, compound and permanent-magnet brushed motors, with separately excited variants when someone wants a lab bench of knobs. On the AC side you really only meet four families in modern work: universal motors, repulsion motors, repulsion-induction motors and a shrinking niche of three-phase commutator machines.

Once you accept that split, “type” becomes shorthand for three things: how the field is produced and connected, how speed reacts to load, and how forgiving the commutator is when you mistreat it with transients and dirt.

DC commutator motor types as they actually show up

Textbooks list separate excited, self-excited, shunt, series, cumulative compound, differential compound and permanent-magnet. In real projects, most engineers are only juggling three profiles and two edge cases.

The series DC motor is the blunt instrument. Field and armature share the same current, so torque at low speed is strong and speed at light load wants to run away if you let it. That makes it suitable for high impact starting requirements where you can mechanically prevent overspeed, and very awkward anywhere a failed load could disconnect the shaft. When someone says “high starting torque DC motor” without qualifiers, they often mean this one and they are usually thinking about cranes, hoists or traction retrofits.

The shunt DC motor plays the opposite role. Field current is mostly fixed by the supply, armature current swings with load, speed hardly moves if you stay within thermal limits. This is boring in the best possible way: steady-speed drives, fans and pumps in older plants, test rigs where a few percent regulation is enough and nobody wants to pay for sophisticated electronic drives. Its weak spot is starting torque; if your load demands a steep pull from zero, you either oversize the frame or pick a different type.

Compound DC motors sit between those two and are the most mis-specified. They combine series and shunt windings, either reinforcing each other (cumulative) or opposing (differential). Cumulative compound machines give you a shunt-like normal operating regime with extra push at low speed, which is often all that is required for conveyors, presses and general-purpose industrial drives. Differential compound machines look interesting on paper but become unstable in many regimes and rarely survive contact with conservative specifiers.

Permanent-magnet DC motors collapse the field circuit into magnets. That removes copper, removes field losses and leaves you with a torque constant, a speed constant and very little to compensate with. Great when you want compactness and efficiency and you are happy to do speed control with electronics or simple armature voltage variation. Much less flexible when you want field-weakening tricks for extended speed range.

Separately excited motors still appear when you want the blunt simple mechanical structure of a brushed DC machine but with laboratory-style freedom over field and armature. Think test stands, educational rigs, or installations that started life before good power electronics and are maintained now because they still run and nobody wants to touch them.

If you read all that and thought “this is just four torque–speed curves with different knobs,” you are reading it correctly.

AC commutator motor types: when the grid is not friendly

On AC, the commutator is stressed harder, ironically making types fewer. Most modern consumer products that still use brushes have converged on one type: the universal motor. It is essentially a series-wound commutator machine designed to work acceptably on both AC and DC, with field and armature reversing together on every half-cycle so torque stays in the same direction. Its frequency range is narrow but that is fine for mains-powered drills, mixers and vacuum cleaners. High speed, good starting torque, terrible acoustic behavior and limited life at full stress.

Repulsion motors are more of a historical and niche industrial species now. They use a stator with single-phase AC field and a rotor with a commutator and short-circuited brushes, operating somewhat like a transformer with shifted rotor currents. The attraction is large starting torque with decent power factor compared to early induction motors. The downside is complexity, brush adjustment issues and a mismatch with modern expectations of low maintenance.

Repulsion-induction motors combine a repulsion rotor with an induction cage. Starting behavior looks like a repulsion motor; once near synchronous speed, the cage takes over and the machine behaves more like an induction motor. This mix gave older designers a way to get both strong starting and acceptable running efficiency off single-phase lines before inverter-driven motors became standard.

Three-phase commutator motors exist in heavy industrial documents and some legacy machinery. These are essentially wound-rotor induction or synchronous machines with commutators providing variable resistance or EMF control in the rotor circuit. They offered smooth wide-range speed control from constant-frequency supplies. The price is mechanical complication and maintenance that few modern plants accept now that electronic drives can do similar electrical tricks without brushes.

Comparative view: where each type tends to make sense

The usual online guides put each type in its own tiny box. The more useful view is to compare them along the axes that actually govern selection: supply, torque behavior, control needs and how much trouble the commutator will give you over years.

| Motor type | Supply and field arrangement | Typical rating band | Torque and speed behavior in real use | Control approach usually chosen | Noise, EMI, and maintenance tendency | Common patterns of use today |

| DC series | DC, field in series with armature | From small traction units up to large cranes | Strong starting torque, speed rises sharply as load falls; runaway risk if shaft load is lost | Simple voltage control plus mechanical limits, or legacy rheostats; sometimes paired with crude electronic choppers in retrofits | High brush wear under repeated heavy starts; notable sparking if commutation is not kept within rated current; audible brush noise | Old cranes, hoists, traction conversions, test stands where the mechanics are already designed around this curve |

| DC shunt | DC, field in parallel with armature | Small to medium industrial frames | Reasonably flat speed–torque characteristic over normal range, modest starting torque | Armature voltage control or basic closed-loop regulators; field weakening for modest overspeed when needed | Brushes run relatively gently if current ripple is controlled; EMI acceptable if wiring and suppression are done correctly | Legacy industrial drives, small machine tools, older pumps and fans, educational rigs |

| Cumulative compound DC | DC, both series and shunt windings reinforcing | Medium industrial sizes | Between series and shunt: improved starting torque with better speed stability than pure series | Traditional multi-step controllers or modern DC drives using both armature and field control | More complex field system to maintain; otherwise similar to shunt or series depending on loading | Conveyors, presses, rolling applications that still keep older DC installations in service |

| Permanent-magnet DC | DC, field from permanent magnets | Fractional kilowatt up to a few kilowatts, sometimes more in specialized frames | Linear torque constant, speed proportional to voltage minus drops; no field weakening unless you accept demagnetization risk | Simple PWM armature voltage control with feedback; easy to integrate into low-cost electronics | No field copper or field failures, but magnets are sensitive to heat and abuse; brushes still wear | Small drives, robotics, actuators, compact tools where commutator technology is still acceptable |

| Universal motor | AC or DC, effectively series wound for AC | Mostly sub-kilowatt, high-speed designs | Very high base speed, strong starting torque, speed falls with load; can be dangerous at no-load if not constrained | Often uncontrolled except for simple phase-angle controllers; feedback only in better appliances | High acoustic noise and brush wear; substantial EMI without proper suppression components | Hand tools, household appliances, small machines where weight and size matter more than life or noise |

| Repulsion motor | Single-phase AC, stator field with rotor commutator and shorted brushes | Mainly older medium-power motors | Very strong starting torque and reasonable power factor, speed closer to synchronous | Mechanical brush shifting for control in older installations; rarely used in new designs | Brush and commutator setting is critical; maintenance heavier than induction motors | Legacy single-phase installations, some specialized applications retained for compatibility |

| Repulsion-induction motor | Single-phase AC, repulsion rotor with embedded induction cage | Similar to repulsion motors | Good starting torque, then transitions to induction-like running with more stable speed | Mostly fixed-speed operation with simple controls, relying on inherent characteristics | Slightly less demanding on brushes in steady operation than pure repulsion types; still not low-maintenance | Older machinery needing both strong starting and stable running on single-phase supplies |

| Three-phase commutator motor | Three-phase AC with commutated rotor circuits | Medium to large industrial machines | Wide-range speed control at near-constant torque or power, depending on rotor circuit configuration | Mechanical or electro-mechanical adjustment of rotor resistance or EMF; today often replaced by electronic drives | Complex commutator systems, higher failure modes, extensive maintenance requirement compared to cage induction motors | Legacy heavy drives where replacement is expensive or constrained by process requirements |

The table is not academic. It simply mirrors how engineers and maintainers talk about these machines when money and downtime enter the conversation.

How selection really happens on projects

Once someone has declared “we will use a commutator motor” instead of an induction or brushless machine, the rest is usually decided by three constraints: the supply, the torque profile and the attitude toward maintenance.

If your supply is only single-phase and you need strong starting torque with simple controls, history pushes you toward universal or older repulsion-family motors. The first dominates household and light tools because it is cheap and compact, even though it is noisy and wears fast. The second persists only where replacements are hard or standards are frozen.

If you already have DC infrastructure, the choice among series, shunt, compound and permanent-magnet tends to follow the shape of the load torque curve. High surge and intermittent duty often lead to series or cumulative compound. Flat torque and long steady runs favor shunt or permanent-magnet, with shunt used when you want thermal robustness and PM when size and efficiency push harder than flexibility.

Speed control expectations matter a lot more than many introductions admit. Where the requirement is “about this speed, give or take a few percent,” a shunt or compound DC machine with a simple regulator works. Where you need a wide speed range and fine tuning but still insist on a commutator, separately excited arrangements linger because you can play with field and armature independently without redesigning the machine frame.

Maintenance philosophy quietly kills off options. Plants aiming for minimal routine intervention avoid AC commutator motors entirely and will keep them only as long as a retrofit is more painful than ongoing brush service. Installations that still accept regular manual maintenance, often because operators are on site around the clock anyway, are the ones where complex commutator machines remain.

Less-visible drivers: noise, EMI and compliance

Standards and compliance do not care about the elegance of your torque–speed curve. They care about conducted and radiated emissions, safety margins and thermal behavior. Commutator motors are naturally noisy electrically because switching happens mechanically at the rotor, with geometry imperfections and wear adding variability.

Universal motors in particular need suppression networks, shielding practices and sometimes special brushes to keep inside EMC limits on modern appliances. That adds components, volume and heat, which is one reason compact brushless designs have taken so much of their earlier share.

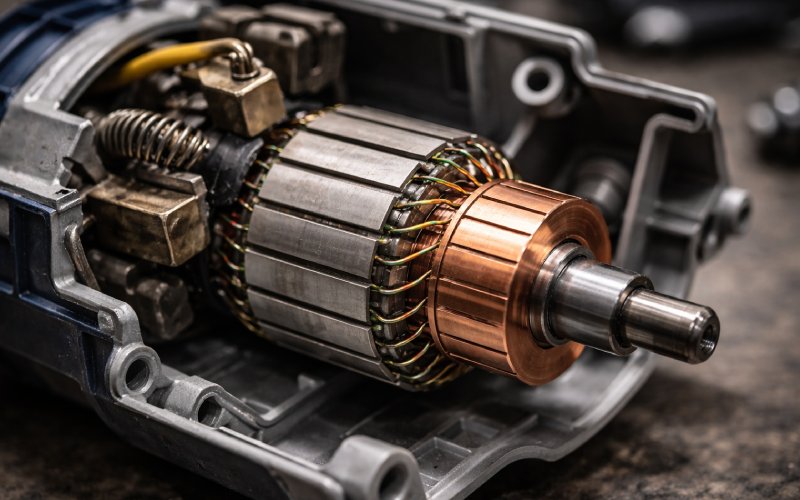

On DC machines, brush grade choices, commutator segment design and cooling all feed into whether the motor behaves predictably across its life. A design that looks good on a fresh test bench can become troublesome after thousands of hours if brushes glaze, mica rises, or the cooling path clogs. These are not just maintenance concerns; they feed back into whether a type remains acceptable for new designs in regulated industries.

There is also the safety aspect of overspeed. DC series and universal motors can accelerate quickly if the mechanical load is lost. That risk does not disappear just because you specify a nameplate correctly; it needs mechanical or electronic protection and sometimes influences whether auditors are comfortable with the type in certain applications.

Coexistence with modern drives

Given the prevalence of inverter-fed induction motors and brushless machines, the obvious question is why anyone still talks about commutator motor types at all.

Sometimes it is pure legacy. An old crane or production line designed around the torque shape and response of a series DC machine may run acceptably for decades, with a known maintenance regime and spare parts. A full redesign to induction plus inverter is sensible long term but expensive in the short term, so the commutator machine stays, maybe paired with a modern DC drive instead of rheostats.

Sometimes it is about peak power density in small consumer tools, where universal motors still offer a straightforward way to get high shaft speed from a simple rectified or phase-controlled mains feed. In those cases the surrounding product architecture already assumes brush replacement is acceptable or the product life is short.

There are hybrid schemes too: using commutator motors as auxiliary drives in systems otherwise driven by electronic converters, or in environments where EMI from high-frequency switching is harder to manage than brush noise.

Closing notes

If you strip away the historical naming and the long taxonomies, commutator motor “types” are just different answers to three questions: how you feed the field, how you accept the resulting torque–speed behavior, and how much attention you are willing to pay to brushes and commutator over time.

Once those are answered honestly, the short list usually writes itself. The rest of the effort goes not into arguing series versus shunt on a whiteboard, but into making sure the chosen type actually fits the real electrical, mechanical and regulatory environment it is dropped into.