Commutator Manufacturing Process – From Copper Segments to Finished Commutator

If the copper segments, insulation scheme, and molding conditions are right on the day you lock the tool, the commutator is already “made”; turning, undercutting, and balancing simply expose whether you respected the physics or tried to negotiate with it.

Table of Contents

What actually decides whether a commutator behaves

Most public documentation explains what a commutator is: copper bars, mica between them, resin or steel hub, carbon brushes on the surface. The practical question in a factory is quieter: what determines whether those segments stay where they should, stay insulated, and run clean for thousands of hours.

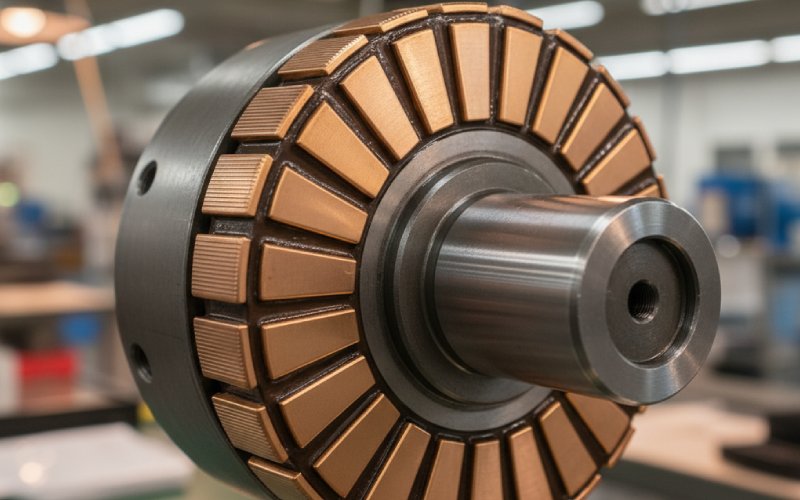

Across different designs the structure is similar. Copper segments (or a copper cylinder later slit into segments) are insulated from each other and from the core by mica or molding compounds, often phenolic-based. The segments are locked into a resin or mechanical support. The whole assembly is machined, mica is undercut slightly below the copper, and the rotor is balanced and seasoned.

Nothing exotic so far. What separates an average commutator from a stable one is how you manage three things during manufacturing: residual stresses in copper, the interface between copper and insulation, and the concentricity chain from shaft to commutator surface. The rest is housekeeping.

Step 1 – Copper segment stock and geometry

Most guides start from “copper bar = given”. On a real line, it rarely is.

For segmental commutators, copper generally arrives as trapezoidal strip lengths, then is cut to segment length (brush length plus riser width, plus machining allowance). Segments are punched into their final L shape, V-grooves and riser slots formed, and extra allowance left for plain and profile turning. Each of these small plastic deformations stores stress; each is a future distortion waiting for your curing oven.

Grain direction matters. When you curl a flat copper plate into a cylinder and later slit it into segments, as in some molded designs, the rolling direction and curvature interact with centrifugal loads. If you think of the copper only as “high-conductivity material” and not as a stressed spring, you get segment lift at high speed and unexplained brush wear.

Segment ends and edges decide how your mica or molding compound flows. Sharp internal corners invite resin voids and mica cracking. Over-generous radii, on the other hand, eat into brush track width. The best shops treat segment geometry like a tooling interface, not just a drawing requirement: slightly modified radii, consistent burr direction, controlled sag in slotting fixtures.

The riser is another quiet player. Slots milled in the riser area for larger commutators create local stiffness changes. Poor riser geometry doesn’t show up in your first continuity test, but it shows up when the first field failure reports “loose connection at high current” and everyone blames the brush grade.

Step 2 – Insulation, mica, and molding compounds

In most traditional commutators, segment insulation is mica. It survives the heat and pressure during assembly and operation better than many alternatives, which is why standards and older repair manuals keep coming back to it. Mica sheets are punched to match copper segment shape, often with extra length towards the riser for projection and later undercutting.

Two mindsets appear here.

In a classic built-up mechanical commutator, the stack is copper–mica–copper around a hub, with V-rings or wedges providing radial and axial locking. In molded commutators, copper segments or a copper cylinder are anchored in a thermoset molding compound (phenolic, often called “Bakelite®” in trade discussions).

Once you move to molded designs, the molding compound becomes a structural component, not just insulation. Phenolic systems for commutators typically mix resin, curing agent, catalyst, fibers, mineral fillers and release agents, tuned so that the molded part reaches flexural strengths above roughly 180 MPa and stable insulation resistance even above 200 °C. This is why the compound supplier asks uncomfortable questions about your cure schedule and not just your color preference.

The key point: copper, mica, and resin will never share the same expansion coefficient or moisture response. The manufacturing process is really about deciding where the mismatch can be absorbed without cracking, bar lift, or tracking.

Step 3 – Building the copper–insulation structure

There are two main families of process routes that matter for copper segment commutators.

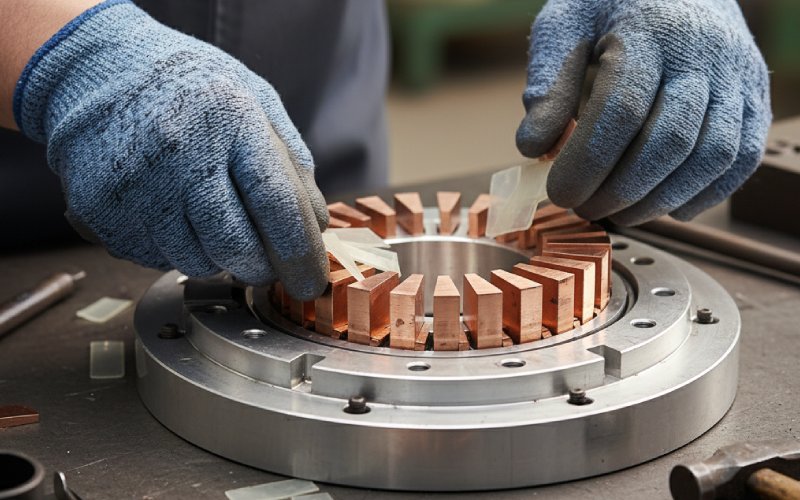

One route starts from discrete segments. Copper lengths are cut to segment size, punched, grooved, and slotted. Matching mica separators and sometimes mica V-rings are prepared. The commutator is assembled with alternating copper and separator mica, checked for segment count, skew, and cage tightness, then clamped. The copper–mica stack forms the “bar ring”, sitting around a machined hub or bushing.

Another route, common in molded types, starts from a copper plate with cladding that is curled into a cylinder. The cylinder is placed in a mold, a resin boss is formed in the central hollow, and only after molding is the copper cylinder slit longitudinally to create the individual segments. Variants use a center bushing with external lugs; fixed-length rods tie the lugs to individual copper segments, forming a copper bar frame, which is then embedded into a die filled with molding powder.

From a process engineer’s chair, the questions are not about which patent family you liked reading. They are about controllability.

With pre-segmented mechanical designs, your risks are misalignment, unequal segment gaps, and mica damage during clamping. With molded designs, your risks are resin flow shadows, poor anchoring of the copper, and internal voids. Mechanical designs are more repairable and refillable; molded designs are often lighter, cheaper in high volume, but typically scrapped when shorted or grounded.

Segment gap uniformity at this point quietly controls everything downstream. Poor control here produces runout that you cannot really “turn away” later without sacrificing life.

Step 4 – Molding and curing the body

Once the copper–insulation cage or cylinder is in place, the next stage is to lock it into a stable body.

Compression molding is still common. Pre-mixed molding compound, made via ribbon blending and extrusion or calendering and grinding, is dosed into the heated mold, compressed, and cured under defined pressure and temperature. Injection-type phenolic compounds exist specifically to speed up commutator molding and to allow smaller diameters. They use tailored phenolic resins, fibers, and fillers so they can flow in thin sections without sticking the mold, while maintaining mechanical strength and insulation.

The big hidden variables are fill pattern and venting. If resin flow fronts meet around a lug or a thickened portion of the copper, they can trap air and release agents. That region later becomes a hot-spot in thermal cycling or a path for tracking. Packing that looks “reasonable” in simulation still needs destructive sectioning on early production to build trust.

Cure profiles also interact with copper stress. A cure that is too aggressive, especially in the early stages, can bake in large gradients between copper and resin, which later relax during turning or in service. A cure that is too gentle may leave undercured pockets behind heavily shielded areas.

At this stage, some manufacturers also integrate additional features such as varistor pins between segments to limit surge voltages and reduce brush sparking, but that only works if the molding and cure keep those pins mechanically locked and electrically consistent.

Step 5 – Machining, undercutting, and profiling

After molding and cure, the raw commutator blank does not yet behave like a commutator. It behaves like a cured, slightly distorted composite assembly. Machining converts it into a controlled surface.

The classic goals are not secret: the commutator surface must be smooth, concentric with the shaft, with proper diameter and adequate undercut of mica. On the shop floor, though, “concentric” hides several different runout numbers: total indicated runout of the commutator surface, runout relative to the bearing seats, and segment-to-segment step variation.

Turning is performed with carefully chosen feeds and tool geometry to avoid smearing copper over mica, especially in smaller molded units. Flood coolant rarely appears in the glossy brochures, but it shows up quickly when chasing thermal stability of dimensions. On large machines, the armature may be set up in a lathe and the commutator turned true with respect to the bearing journals.

Undercutting is where many “OK on paper, noisy in service” commutators are created. The process removes insulation between segments (often mica, sometimes molded materials), leaving it slightly recessed below the copper surface. This recess lets the brushes bridge from bar to bar without riding on hard insulation, reducing arcing and wear. If the undercut is too shallow, insulation interferes with the brush and accelerates wear; too deep and you weaken segment support and encourage carbon packing.

Undercutting tools and methods vary: saws, milling cutters, or special undercutting machines with controlled depth and feed. On smaller commutators, manual undercutting with thin saws is still found, but consistency then depends heavily on operator skill. On larger or high-speed units, automated machines maintain mica depth and slot width within very tight limits.

Edge breaking around each bar, polishing, and cleaning complete this stage. Residual burrs or carbon dust bridges between bars can undo a lot of meticulous earlier work.

Summary table – From segment blanks to finished commutator

| Manufacturing stage | Main operations (typical) | Common hidden risks | Key control levers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper segment preparation | Cutting, punching L-shape, V-grooves, riser slotting, deburring | Residual stress, variable bar width, burrs that disturb mica or resin flow | Tool design, burr direction control, inspection of segment geometry and flatness |

| Insulation and cage assembly | Mica punching, stacking copper–mica, clamping, bushing or lug integration | Cracked mica, unequal segment gaps, skew errors | Assembly fixtures, controlled clamping force, intermediate runout and gap checks |

| Molding and cure | Loading molding compound, compression or injection molding, curing, cooling | Voids, incomplete wetting around lugs, residual cure stress | Compound selection, fill pattern, venting, cure profile, destructive sectioning in process validation |

| Turning and undercutting | Rough and finish turning, surface finishing, undercutting insulation, edge breaking | Smearing copper over insulation, uneven undercut, chatter marks | Rigid setups, tool geometry, depth control on undercutting machines, surface inspection |

| Balancing and seasoning | Dynamic balancing, over-speed spin, thermal cycling, electrical tests | Latent segment movement, early tracking, brush seating problems | Spin seasoning, controlled load tests, inspection after test runs, feedback to earlier stages |

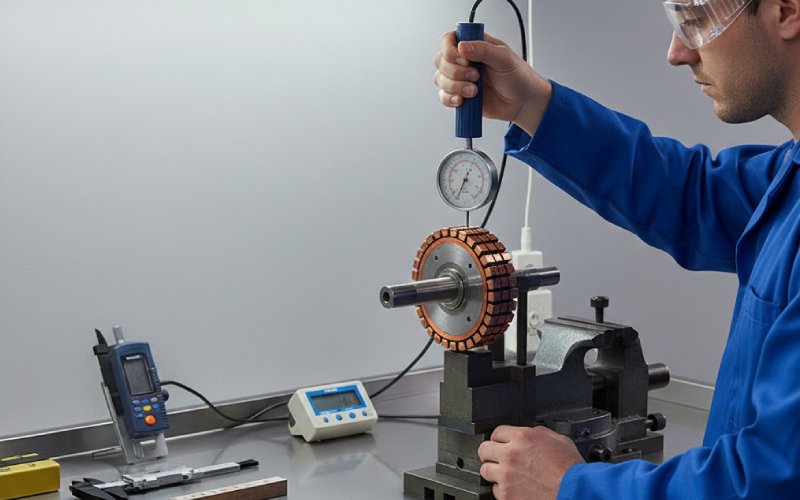

Step 6 – Balancing, seasoning, and test

Up to now, most issues have been geometric or material-related. The last stage checks whether the assembly behaves under real loads.

Large industrial commutators may undergo over-speed spin testing or “spin seasoning” to guarantee stability of segments and insulation under centrifugal and thermal stress. During such tests, any marginal bonding between copper and resin, or minor gap in the cage, tends to show up as movement, cracking, or changes in runout.

Dynamic balancing removes residual unbalance introduced by manufacturing tolerances. It is usually carried out on the full rotor assembly, not just the commutator, but the commutator’s eccentricity often dominates the correction required. Inadequate balance does not just mean vibration; at high speed it means variable brush pressure and uneven wear.

Electrical checks follow: insulation resistance, high-potential tests, sometimes surge or bar-to-bar tests depending on the application. While these are often considered “armature tests”, they reveal local insulation weaknesses near the commutator as well.

Finally, brushes are seated against the commutator surface, often by running the machine with reduced load and sometimes with fine abrasive seating stones. Poorly machined or poorly cleaned commutators show themselves quickly here as uneven brush tracks or early sparking.

Design choices that quietly reshape the process

Manufacturing is not independent of design; small design decisions change the process window.

Higher-speed machines demand stronger anchoring of segments. This can mean reinforced molded designs with rings, or deeper mechanical locking in dovetail constructions. In some molded units there is simply not enough radial space between core and copper to cut V-grooves and add V-rings without losing copper strength, which is why replacement designs cannot just copy a mechanical commutator pattern.

Temperature class and duty cycle also feed back into choice of phenolic compound, filler type, and mica thickness. High-temperature operation increases the importance of thermal expansion mismatch; what looks fine at 80 °C may start cracking at 160 °C.

Even brush grade feeds back into manufacturing. Carbon with high copper content may tolerate slightly different surface finish than pure carbon grades. The undercut depth and edge radius that works with one brush family can give noisy or sparking operation with another.

The strongest factories are the ones where design and process engineering are in constant argument. They treat segment geometry and molding parameters as a combined system, not separate departments.

What this means when you walk the line

If you already know the theory of commutation, the manufacturing process is where your real leverage sits.

When you are at the copper punching station, the question is not just “are we within drawing tolerance,” but “are we creating a stress pattern that the molding and curing can relax, or one that will wait and disturb us during turning.”

When you are approving a new phenolic or mica source, you are not just buying insulation. You are choosing how the commutator breathes under load and cool-down.

When you are standing at the undercutting machine, any temptation to relax depth control is a decision about brush life, not about machining minutes.

From copper segments to finished commutator, the steps are well known. The difference between an ordinary product and a stable one comes from how seriously you treat those “small” interfaces and transitions that never quite fit into a simple checklist.