Commutator Bar Burning: Reading The Damage Before It Owns Your Machine

Commutator bar burning is not random punishment from the machine; it is structured feedback. If you learn to read the burn pattern against the history of that motor or generator, you can usually decide, with a straight face, whether you need a quick skim, a settings correction, or a full rewind — and you can reach that decision sooner than the failure reaches you.

Table of Contents

Starting where the film charts stop

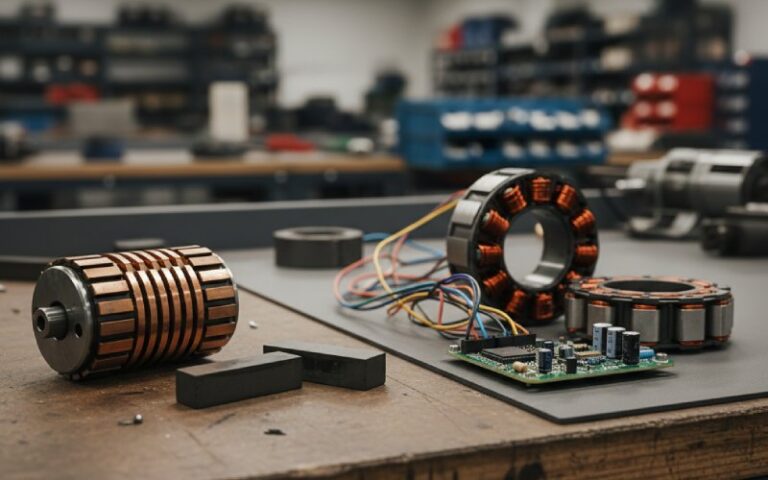

You already know the textbook description. Bar burning shows up as erosion on the trailing edge of one or more commutator bars. In many machines it repeats in a fixed sequence, every second or third bar, or in groups that line up with brush arm spacing. Reference charts from brush and carbon specialists call these bar burning, slot bar burning, and pitch bar burning, and they point to causes like poor electrical symmetry, brush selection, and mechanical disturbance, with a clear warning about flashover if the pattern is ignored.

All of that is correct, and still not quite enough on a running plant. Real machines arrive with context attached: recent rewinds, uneven loading, bearing changes, damp environments, rushed repairs. The commutator surface becomes a summary of those decisions. So the question shifts. Less “what is bar burning?” and more “given this specific pattern, on this specific duty cycle, what is the machine trying to tell me right now?”

A useful mental model is to treat every instance of commutator bar burning as the intersection of three things: pattern, context, trend. Pattern is what you can see in the copper. Context is what you know about how the machine has been used and serviced. Trend is whether the damage develops slowly with hours, or leaps forward between short inspections. Reading all three together is what moves you beyond the generic troubleshooting tables.

Pattern-first thinking: what the burn is actually saying

Charts from Morgan, Electrographite and others do a good job of naming the surface patterns: uniform bar burning, slot bar burning, and pitch bar burning, each with its own geometry on the commutator. The gap is not in the names, but in what you choose to check first, and how hard you push the machine once you have seen them.

The table below is written with that in mind. Each row assumes you already recognise the pattern. The emphasis is on what it usually means in practice and where experienced service engineers tend to look first.

| Pattern on the commutator | Typical root issues in real machines | First things worth checking | What usually happens if you keep running |

| Isolated bar burning on a small group of bars, often near one brush arm | Localised heating from a weak or fractured riser, a poor equalizer connection, or a single coil with higher resistance; sometimes combined with uneven brush pressure on one arm | Measure bar-to-bar and riser resistances on the suspect sector, compare against a similar sector; confirm brush pressure and brush freedom in the holders for that arm; check recent repair records for partial rewinds or replaced coils in that zone | Damage tends to deepen on the same bars, eventually undercutting the mica and encouraging arcing at that localised spot, with a high chance of having to replace or completely refinish the commutator section |

| Slot bar burning: erosion repeating every second, third, or fourth bar around the ring | Combination of brush bounce, incorrect brush material for the duty, or electrical adjustment issues such as neutral shift or interpole strength mismatch; often aggravated by contamination in the air path | Confirm neutral setting under normal load, not just at standstill; check interpole polarity and magnetisation; verify brush grade against present load pattern; inspect for vibration and airborne dust at the motor location | The repeated pattern cuts grooves along the bar sequence, brush life drops, sparking increases and the machine moves toward flashover or costly commutator replacement if action is delayed |

| Pitch bar burning: bars eroded in groups tied to half the number of brush arms, later matching the number of arms | Cyclic electrical or mechanical disturbance such as unbalanced armature, misaligned shaft, weak foundation, failing bearings, or open equalizers; the disturbance “beats” with the brush arm spacing | Review vibration data across the speed range; check shaft alignment and bearing condition; electrically test equalizers; correlate burn pattern with past episodes of overload, starting duty, or speed variation | The pattern sharpens with operating hours; once the disturbance grows, the machine becomes prone to flashover and sudden commutator damage rather than slow, predictable wear |

| Broad, uniform darkening with mild trailing-edge wear over much of the circumference | Often not pure bar burning at all but a mix of light overload, imperfect film, and minor mechanical issues; common after a process change or brush grade swap | Confirm that current density and brush spring pressure are inside the band recommended by the brush supplier; review recent process changes that altered load profile; check cooling and humidity conditions against the original design assumptions | Condition can stabilise if loading is corrected and film recovers; if current density stays marginal or cooling is poor, the pattern slowly transitions to true burning with visible edge erosion |

Tables like this do not replace the factory documentation. They sit beside it. The aim is to shorten the path from “I see this pattern under the inspection lamp” to “here are the three things I am going to measure next, in this order.”

Let the burn guide the inspection, not the other way round

On a real job, your time on the machine is usually limited. So it makes sense to let the burn pattern dictate the sequence of checks, not a generic checklist.

With isolated bar burning, the fastest path is usually electrical. The commutator is telling you that some bars are carrying more heat than their neighbours. That almost always means extra current or extra resistance. Before worrying about global settings, you look for that local bottle-neck: a poor solder joint, a tired riser, a coil that has lost some cross-section, an equalizer that is not sharing current as designed. Bar-to-bar resistance comparison in the suspect sector, cross-checked against a “clean” sector, is often enough to tell you whether the issue is inside the armature or at the surface.

Slot bar burning, by contrast, rarely surrenders to a single measurement. The repeating pattern every second or third bar points back to the relationship between armature slots, interpoles, and brush arms. It is a system symptom, not a local defect. Here, starting with neutral setting, under load, makes sense. Then you look at interpole strength and polarity, with an honest look at how close your current operating point is to what the machine was built for. Contamination and airflow also deserve more attention than they often get; several guides note how abrasive or dirty air can reshape wear patterns and aggravate burning.

Pitch bar burning is more awkward still. Its pattern is tied to the spacing of the brush arms, but its roots are often mechanical. The commutator becomes a kind of printout of whatever cyclic disturbance is passing through the shaft and frame. The burn groups do not simply tell you that the brushes are mis-set; they hint that the armature, the support structure, or the equalizer network are moving in and out of step with one another. That is why serious pitch bar burning is usually handled with vibration data, alignment checks, and sometimes a hard look at the foundation bolts before touching the brush gear.

When you treat commutator bar burning like this, as a structured signal that chooses your next measurement for you, the inspection stops feeling like a long list and starts behaving more like a conversation with the machine. A somewhat blunt one, but still a conversation.

Trend matters more than the snapshot

Two machines can show almost identical slot bar burning on a given day and still demand very different responses. The difference lies in the trend.

If bar burning has crept up slowly over several oil-change intervals, with film condition, sparking level and brush length all shifting in sync, you are looking at a slow drift. Maybe a mis-set neutral from an earlier service, maybe a brush grade that was “good enough” but not ideal. In such cases, modest corrections and a scheduled skim often restore order, provided cooling, load and environment are brought back into line.

If, instead, the commutator was clean three weeks ago and now shows sharp trailing-edge damage, bright spots in the film, and rising sparking levels, the story is different. Bright patches and under-brush sparking are strong clues that local contact is failing, the patina is being stripped, and the burning is now feeding on itself. Here, waiting for the next major outage becomes a calculated risk. The machine is telling you that the window between “visible damage” and “flashover” may be short.

Trend also shows up in the way brushes wear. Where slot bar burning is mainly driven by electrical adjustment, brush faces often show corresponding patterns but remain mechanically healthy. When vibration is dominant, the brush edges can chip, the holders show fretting, and you may see carbon dust in places where it does not belong. These small details help you decide whether to call for a quick brush change and re-setting, or to push for a broader mechanical investigation.

Deciding how hard to intervene

A common frustration in maintenance planning is balancing the cost of intervention against the risk of letting a pattern evolve. With commutator bar burning, you can structure that decision around three questions.

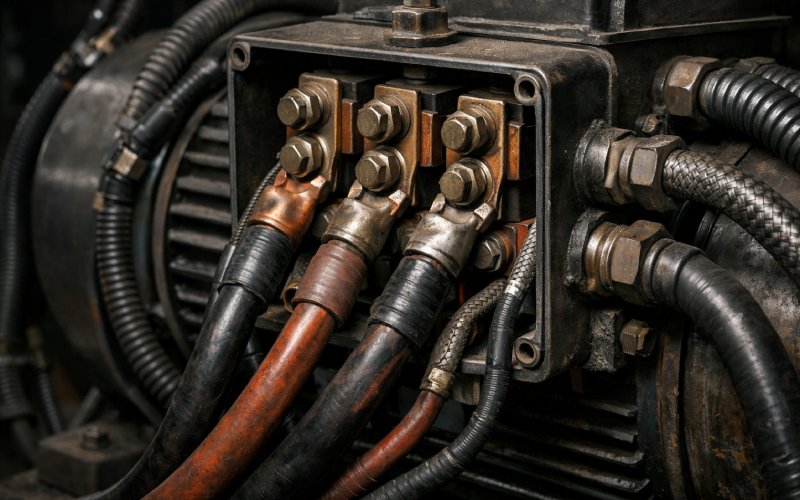

First, how close are you to flashover territory? Charts from suppliers make it clear that unattended bar burning can end there, especially when combined with copper drag and degraded insulation between bars. If sparking level is already high, if there is metal build-up at bar edges, or if there is evidence of tracking across mica, the safe choice is to plan an urgent intervention, even if it means an unplanned outage.

Second, how much healthy copper remains? Manufacturers usually specify a minimum commutator diameter. Service engineers often work with simple practical rules: a light skim that removes only superficial burning and restores roundness can be acceptable early in the life of the commutator; repeated or deep skims that push you toward the minimum diameter indicate a different kind of decision, one involving a rewind or replacement.

Third, how confident are you that you have found the root cause upstream? Skimming a commutator or changing brushes without addressing equalizer problems, neutral setting, or mechanical disturbance is almost an invitation for the same pattern to return, sometimes more aggressively. Once you have evidence pointing to, say, weak foundations or structural resonance, it becomes rational to spend more time on that, even if the burning today is moderate.

None of this requires new theory. It mostly requires the discipline to read the pattern, the trend, and the upstream system together, instead of treating bar burning as a purely local surface defect.

Making bar burning part of normal feedback, not just a failure mode

In a lot of plants, commutator inspection happens as an exception, triggered by noise, smell, or interlocks. That is understandable, but it wastes information. Bar burning starts small. The initial signs appear as slightly stressed film, tiny changes in trailing edges, subtle differences in colour from bar to bar. Reference guides explicitly show these as early-warning patterns, not just end-stage damage.

A more systematic approach treats commutator condition as a regular data point, just like bearing temperature or insulation resistance. Each short shutdown, someone looks, under consistent lighting, and records: pattern name, rough severity, location relative to brush arms, and any change since last time. Over months, this builds a quiet story of how the machine responds to real operating life, not just to design calculations.

Once that story exists, commutator bar burning stops being a surprise. You see which machines drift toward slot bar burning whenever you push load above a certain point. You notice where new brush grades improve film but create new wear patterns. You spot when a foundation repair really did stabilise a stubborn pitch bar burning issue, because the pattern stops growing.

This is not about making the machine perfect. It is about letting a damaged commutator teach you something useful before you are forced into emergency work.

Closing thoughts

Commutator bar burning will always be an unwelcome finding, but it does not have to be mysterious. The damage you see on the copper is the visible end of a chain that runs through brush gear, magnetic circuit, structure, and process. By treating the burn pattern as structured feedback, aligning it with what you already know from film charts and manuals, and then tying it to the actual history of the machine in front of you, you gain something very practical: a calmer, faster path from “that does not look right” to a specific plan of action.

The copper will keep talking either way. Deciding to listen earlier is the only part under your control.