How to Make a DC Motor With a Real Commutator

By the end of this build you’ll have a small brushed DC motor that starts reliably, runs off a low-voltage supply, and uses a proper split-ring commutator instead of scraped enamel tricks or one-use foil hacks.

Table of Contents

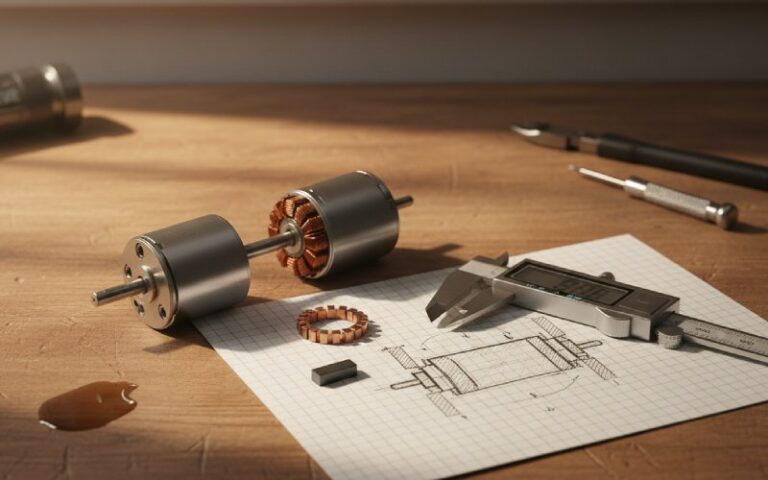

What you’re actually building

You’re not making the usual “paperclip-and-battery” demo. The goal here is a repeatable little machine: an iron-cored armature with two coils, a copper two-segment commutator on the shaft, simple brushes, and a permanent-magnet stator. In other words, the same basic architecture used in real commercial DC motors, just stretched out where you can see everything.

The physics is assumed. You already know that armature current, magnetic field and torque are tied together, and that the commutator redirects current every half-turn so torque keeps the same sign.

Here we care about build choices, not theory.

Key design choices at a glance

This is the target spec used through the guide. You can drift a bit; the motor will mostly forgive you.

| Item | Target for this build | Why this ballpark works |

| Supply voltage | 3–6 V DC (AA pack or bench supply) | Safe, no mains work, current still large enough for visible torque |

| Armature core | Steel rod or nail, about 6–8 mm diameter, 40–60 mm long | Gives a clear magnetic path and decent inertia without being heavy |

| Wire | 0.25–0.3 mm enamelled copper (approx AWG 30–32) | Thin enough for 5–10 Ω total winding, thick enough to survive handling |

| Coils | Two coils, about 90–110 turns each | Keeps current reasonable while still producing good torque |

| Commutator | Two copper half-rings on the shaft | Classic two-pole DC motor layout |

| Magnets | Two rectangular neodymium or strong ferrite blocks | Simple way to get a strong radial field through the armature |

| Brushes | Springy copper or phosphor-bronze strips | Easy to fabricate and adjust; graphite is optional |

| No-load speed | A few thousand rpm is typical | You don’t need to measure it unless you want to |

You can copy these numbers outright on a first build. After that, you can start abusing them.

Materials and tools, in plain language

You need a short steel rod or large nail for the shaft and armature core, a length of enamelled copper wire, some scrap copper sheet or small copper tube for the commutator, two small strong magnets, a piece of plywood or acrylic as the base, and something that can act as brushes: slivers of copper strip, old relay contacts, even thick copper wire bent into shape. A low-voltage DC source, a multimeter, epoxy or cyanoacrylate, fine sandpaper, a hacksaw, a file and a drill complete the list. A small bench vise makes life easier but is not mandatory.

If you already have a dead DC motor, you can steal the shaft and bearings from it and pretend you machined them perfectly on purpose.

Step 1 – Sketch the geometry before you cut metal

Take two minutes with pencil and paper. Draw the shaft, mark where the coils will sit, where the commutator will sit, and where the magnets will go. Put realistic numbers beside each length on the sketch.

This is where you quietly decide clearances. Leave at least 3–4 mm radial gap between armature and magnets to allow for wobble. Leave enough shaft beyond the bearings to grab the rotor with your fingers. If in doubt, exaggerate distances; the motor will thank you with less accidental rubbing and fewer mysterious stalls.

The sketch does not have to be pretty. It just has to exist.

Step 2 – Build the armature core and shaft

Cut the steel rod or nail to length and file the ends flat. Aim for something like 50 mm of usable length. Deburr the edges; sharp edges cut insulation and later you blame the commutator.

Lightly roughen the central section where the coils will sit with sandpaper. Not into deep grooves, just enough so the wire doesn’t slide off in neat little springs. If you want to be thorough, wrap a single tight layer of thin paper or Kapton tape over that area as insulation and glue it down.

At this point, spin the shaft between your fingers. If it already feels bent, it is. Straighten it now with gentle taps on a hard surface or start over with a better piece of steel. A slightly crooked shaft will still run, just with more vibration than you planned to admit.

Step 3 – Make a real split-ring commutator

Most student motors fake the commutator with partially scraped wire or aluminium foil wrapped around a pencil. It works, but only just.

Here you’ll make an actual two-segment ring.

Cut a short piece of thin-wall copper tube, maybe 12–15 mm long, with an inner diameter just larger than the shaft. Saw carefully along the tube so you get two half-cylinders. Clean the inside and outside faces with sandpaper until they are bright.

Slide a thin insulating sleeve over the shaft where the commutator will live: two layers of paper coated with superglue, or a tight length of heat-shrink tubing. Let adhesive cure properly. Then place the two copper halves around this sleeve with a narrow gap between them, just under a millimetre, and glue them in place with epoxy. Try to keep them aligned so their outer surfaces form a near-circular ring.

You want the gap between segments to run exactly along the shaft, not at some random angle. Don’t obsess, but don’t ignore it either: this gap defines when the current flips in relation to the armature position.

Leave the coil connections for later; for now you just want a sturdy segmented ring that spins with the shaft.

Step 4 – Wind the armature coils and join them to the commutator

Now the repetitive part. You only do it twice, though.

Measure out a long length of enamelled copper wire. If you’re using 0.25–0.3 mm wire and aiming near the design table, about 10–12 metres will be fine for two coils of 90–110 turns each. You can play this smarter by watching resistance on the multimeter as you wind; once total end-to-end resistance creeps into the 5–10 Ω range, you’re in the zone for a 3–6 V supply.

Tape one end of the wire temporarily to the shaft, a little away from the commutator. Start winding the first coil near one side of the armature section. Keep the turns tight and reasonably neat, moving back and forth along the core so the coil forms a short cylinder rather than a ball. When you hit your turn count, lock that coil with a band of tape or a smear of epoxy.

Without cutting the wire, walk along the shaft and wind the second coil on the opposite side, 180° around the core from the first. Same number of turns, same general shape.

Now cut the wire, leaving enough slack at both ends to reach the commutator comfortably. You should have two free ends and one internal connection between the coils.

Scrape or sand the enamel off the two outer ends where they will be soldered. Tin them with solder. Do the same for the small spots on each commutator segment where the wire will attach. Solder one coil end to one segment and the other coil end to the other segment.

The hidden joint between coils can stay insulated; the coils effectively run in series between segments. This is the standard two-pole armature layout: the commutator injects current into whichever coil sides are not near the neutral zone at that moment.

When the solder cools, check continuity: one brush position should see the full coil resistance from one segment to the other. If your meter shows an open circuit, you have at least one break or missed scrap of enamel.

Step 5 – Mount bearings and build a frame the motor can actually sit in

A motor that works only while you hold it in the air is mildly interesting. Better to give it a frame.

Drill two holes in your base for simple bearing blocks. These can be pieces of hardwood or plastic with a snug clearance hole, or salvaged ball bearings if you have them. Many teaching builds use angle brackets and a pencil as the shaft; that also works, but your commutator and coils are already more serious than that.

Align the supports so the shaft sits level and spins freely without rubbing the base. The commutator should be out at one end, with enough space around it for brushes and fingers.

Now add the stator magnets. Fix one magnet to each side of the armature, opposite poles facing each other so the field lines run roughly across the shaft. Glue them to steel angle brackets or directly to the base, just ensure the gaps are even and the armature never quite touches them.

If you look side-on at the motor, the magnets should roughly line up on a horizontal line across the armature. The commutator gap should end up near vertical when the coil faces align with the magnets. You will refine that later.

Step 6 – Fabricate brushes that don’t chatter themselves to pieces

Brushes are just resilient conductors pressed against the commutator segments. Commercial motors often use carbon or graphite; for a visible build, springy copper strip works well and is easier to source.

Cut two thin strips of copper or phosphor-bronze and bend each into a shallow S or leaf shape so the free end naturally pushes against the commutator when mounted. Bolt or screw the fixed ends to the base or to small insulating blocks, positioning them on opposite sides of the commutator.

Adjust the geometry so the brush tips sit roughly at 90° to each other around the ring. That way, when one brush is centred on one segment, the other sits on the opposite segment. The exact angle is not sacred; you will nudge it while tuning.

Run flexible wires from your power source to the fixed ends of the brushes. The brush arms themselves will carry current into the segments. Keep these leads slack so they don’t twist the brushes away as the motor vibrates.

Step 7 – First power-up and the manual nudge

Before applying power, rotate the shaft slowly by hand and inspect. Nothing should scrape. Coils should clear the magnets. The brushes should maintain contact all the way around but not gouge the copper.

Use a multimeter to check that with the brushes pressed on, you see a finite resistance between supply leads that varies a little as you rotate the shaft but never jumps to infinite. This tells you each brush is actually touching a segment and that your coils still form a path.

Now connect a 3–6 V DC supply. A couple of AA cells in series or a bench supply current-limited to around 1 A is fine. Never connect this setup directly to mains, even through a small phone charger; these brush contacts can arc and send noise back up the line.

With power applied, give the rotor a light flick. Expect it to twitch first, maybe rock back and forth once or twice. If the commutator timing is reasonable, it should then fall into continuous rotation. No need for a high-speed spin-up; even a lazy push is enough once everything is aligned.

If it refuses to rotate in either direction, cut power and move to debugging rather than brute force.

Tuning commutator timing without advanced math

Stand the motor so you can see the armature face-on. Pick a reference: for example, call “horizontal” the line joining the centres of the two magnets.

Your goal is simple. The coil sides should experience maximum torque when they line up with that horizontal field, and the current in each side should reverse sign just after the torque would otherwise go to zero.

Practically, this means:

When one coil is horizontal, the brushes should be fully on each segment, not straddling the insulating gap. When the coil passes through the vertical position, the brushes should briefly ride the gap and interrupt current.

If you find that the motor runs better when you manually twist the commutator relative to the coils, you’re just discovering this timing the hard way. Loosen the commutator on the shaft if possible, rotate it by a few degrees, and glue again once you see which direction improves starting torque. If the commutator is already solid, shift the brush holders a little around the perimeter instead. Small adjustments matter more than big ones.

Watch the colour and condition of the segments after a few minutes of running. Heavy sparking and quick darkening usually mean poor timing or too much brush pressure. Light streaks are normal.

Common failure modes and quick checks

Most non-working home-built motors die in the same few ways. You can pass through these checks quickly.

If the shaft binds or drags at any position, fix mechanical issues first. No amount of rewiring will make a rotor spin through a physical collision. Check that the coils aren’t ballooning out and rubbing the magnets, and that the commutator isn’t scraping the brush mounts.

If the rotor is free but you get zero motion, even with a nudge, verify the electrical path from one supply lead, through its brush, into a commutator segment, through the coils, out to the other segment, and finally through the other brush and lead. A continuity test at each interface is usually faster than staring at it.

If it moves but keeps stopping in the same orientation, your commutator gap is probably misaligned. The coil is being energised when it already lines up with the field, so it neither accelerates nor decelerates usefully. Shift the brushes so the gap passes the brushes when the coil is close to horizontal, not vertical.

If it runs but only at very high voltage, the winding resistance may be too high, producing a weak field. Fewer turns or thicker wire fix that. If it runs but current is excessive and everything heats quickly, you went the other way: too few turns or wire too thick. That is what the design table was quietly trying to keep you away from.

If it works once and then not again, suspect loose solder joints on commutator, or brushes that have lost contact because the base warped slightly. Copper work-hardens and springs relax; a small re-bend usually restores pressure.

Making it less crude: upgrades once it spins

Once the first version runs, imperfections stop being a problem and start being useful hints. You have space for refinement.

You can add laminations to the armature instead of a solid steel rod. Many commercial DC motors stack thin insulated iron discs to reduce eddy current losses inside the core. For a demonstration motor this is not essential, but if you want cooler windings and slightly more efficient running, slicing your core into insulated slices moves you closer to that design.

You can move from two poles to three or more. That means three sets of coils spaced 120° apart and a commutator with six segments, where each coil connects across two opposite segments. This smooths torque and improves starting behaviour because there is always at least one coil in a useful position.

You can replace copper strip brushes with graphite rods or commercial motor brushes. That reduces wear on the commutator and gives quieter operation, though it makes brush holders a little more involved.

You can also take the reverse route: disassemble a cheap toy motor and compare its tiny hidden commutator and skew-wound armature to your exposed version. This cross-check often explains why your broad, hand-wound coils behave as they do at higher speed.

Each change alters the current path, commutation angles, and torque curve slightly. Very little of it is “right” or “wrong”; it is mostly about making the motor suit whatever experiment comes next.

Safety and sanity notes

Stay below 12 V and keep current modest. The numbers earlier assume you hold around an ampere or less in steady operation. A bench supply with a current limit is ideal. Battery packs are fine as long as you are aware that shorted brushes can dump a lot of current momentarily. Avoid wiring that can be grabbed accidentally while stripped; even low-voltage arcs can startle.

Do not run the motor stalled for long. When it is not spinning, back-EMF vanishes and current into the coils climbs; they heat, insulation softens, and shorted turns quietly build themselves.

Finally, keep loose clothing and hair away from the spinning shaft. This build leaves everything exposed on purpose; that includes all the ways it can grab things.

Final checks and next build

If you’ve followed through, you now have a brushed DC motor with a real commutator whose geometry you understand because you placed every part yourself. It will probably run slightly rough, hum a bit, and spark more than a commercial unit. That’s acceptable.

The value in this design is that nothing is hidden. You can shift brush angles and literally watch torque change. You can rewind the armature with more turns, or a different wire gauge, and see how starting current and speed move around. You can build a second motor with a three-segment commutator and compare the two.

Once that feels ordinary, you’re already past the level of the usual school-project motor guides. The next iteration is yours, not the textbook’s.