Which Electromagnetic Device Uses Brushes and a Commutator?

Short answer first: the classic exam answer is the DC generator, but in real hardware you meet a whole family of DC machines — generators and motors — that live or die by the pair of brushes and a commutator.

Table of Contents

The exam key vs the lab bench

If you come from quiz banks and entrance-test books, the pattern is almost predictable. The question lists “speaker, DC generator, relay, solenoid” and the key quietly points to “DC generator”.

From a machine designer’s view, that is a little narrow. That segmented copper ring plus carbon brushes is not loyal to generation alone. It is the standard mechanical switching scheme for direct-current rotating machines: dynamos and many DC motors, and universal motors in things like older vacuum cleaners.

So, if you are answering a multiple-choice question, you circle “DC generator” and move on. When you are standing in front of a real machine with the covers off, you say: this is a brushed DC machine, which could be configured as a generator or a motor, and the commutator plus brushes are what make it behave as DC at the terminals.

Why brushes and a commutator exist at all

You already know Faraday, flux, induced EMF, and the whole formal structure. No need to repeat. The more interesting part here is the constraint. You want a rotating armature with conductors cutting magnetic field lines while the external circuit sees current in one direction only.

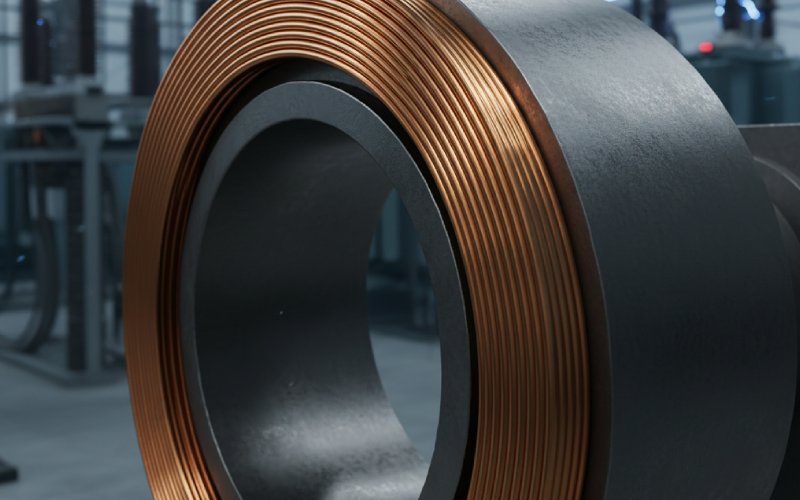

The commutator is a mechanical rectifier riding on the shaft. It divides the armature winding into segments and reverses which segment is connected to the external circuit every half-turn. The brushes are just sliding contacts, often carbon, that stay still in the frame and press on the commutator to pass current.

Everything else in the machine exists so this arrangement does not destroy itself too quickly: geometry of the neutral plane, stiffness of the brush springs, surface finish of the copper, cooling, access for replacement. The electromagnetic theory is almost the easy part compared with getting those few square millimetres of sliding contact to behave for years.

DC generator: the textbook device with brushes and a commutator

If someone asks “which electromagnetic device uses brushes and a commutator?” in the style of a physics test, they are usually thinking of the DC generator. They picture a loop of wire rotating between poles, a split-ring commutator, and two brushes connected to a load. That picture still rules the diagrams in many school notes.

In that mode, the commutator is sampling the alternating EMF induced in the rotating coils and flipping the connections so that the output terminals always see the same polarity. It is a rectifier driven directly by the shaft, not by diodes. The brushes do nothing clever; they just sit in the right place, make contact with the right segment at the right time, and try not to burn up under current and vibration.

The key point that often gets skipped: the generator does not “know” it is a generator. It is a DC machine being driven mechanically. Swap roles, and with the same commutator and brushes you have a motor.

DC motor: same parts, different viewpoint

In a brushed DC motor, the commutator still flips connections every half turn, but now the aim is to keep electromagnetic torque roughly in the same direction as the rotor spins. The brushes feed armature current from the external supply into the right coils at the right angular position.

Most introductory notes on motors quietly mention the commutator and then spend most of the time on Fleming’s left-hand rule. Yet the commutator–brush interface is usually where the field problems show up: sparking at load, uneven wear, noise, armature reaction forcing you to shift the brushes a little off the geometrical neutral.

So while the exam might lean on “DC generator” as the answer, many people first meet brushes and a commutator inside DC motors in tools, toys, and small appliances. Same principle, different direction of energy flow.

What has brushes and a commutator — and what does not

The main confusion comes from mixing ordinary electromagnetic devices with rotating DC machines in the same question. Speakers, relays, and solenoids all use coils and magnetic fields, but they do not need to reverse currents by rotation, so they have no commutator.

It helps to lay out the main devices side by side.

| Device | Uses brushes? | Uses a commutator? | Typical use | How you recognise it quickly |

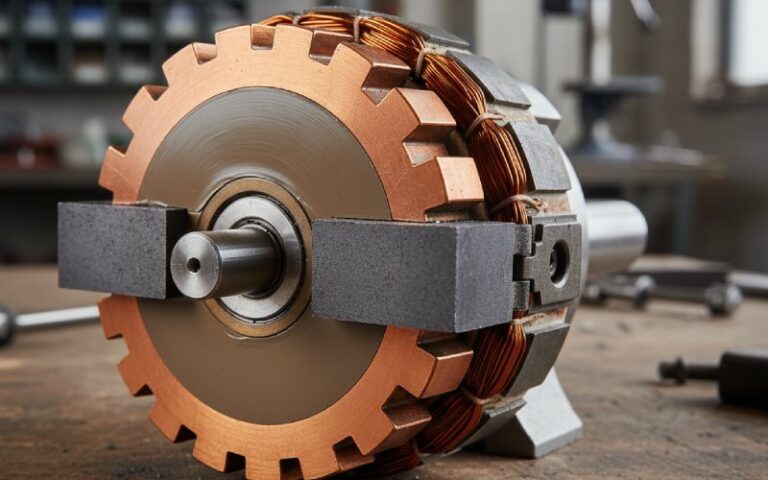

| DC generator (dynamo) | Yes | Yes | Older DC power systems, chargers, test rigs | Cylindrical machine, heavy end-bell, large copper commutator ring |

| Brushed DC motor | Yes | Yes | Tools, toys, drives, actuators | Two fixed brushes, arcing at load, distinct commutator segments |

| Universal motor | Yes | Yes | Mains-powered drills, mixers, vacuum cleaners | Small frame, high speed, brushes, commutator, field in series |

| Loudspeaker | No | No | Audio output | Voice coil in a gap, no rotating copper segments |

| Electromagnetic relay | No | No | Switching circuits | Coil plus moving contacts, but no rotating armature |

| Solenoid | No | No | Linear actuation | Plunger moving in and out of a coil |

| Induction motor | No brushes* | No | Industrial drives, fans, pumps | Squirrel-cage rotor, slip rings absent in standard form |

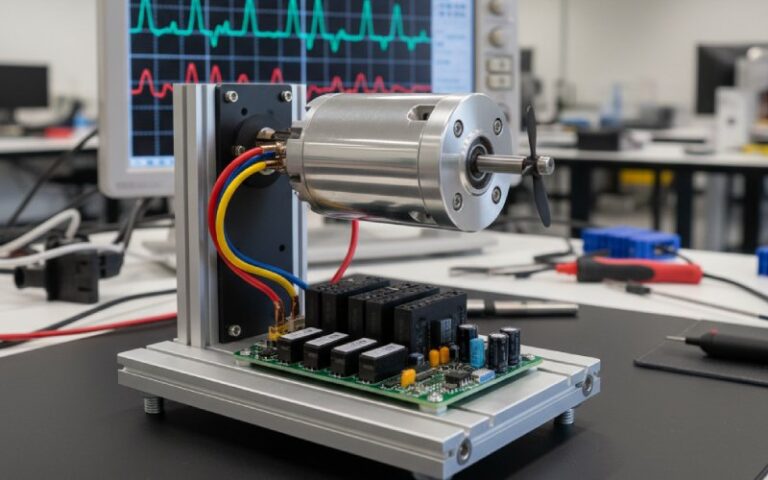

| Brushless DC motor | No | No | Drives with electronic control | Permanent magnets on rotor, electronic commutation only |

*Slip-ring induction motors do use rings and brushes, but they are continuous rings, not commutators, and the function is different.

Once you see that layout, the multiple-choice answer stops being mysterious. Among “speaker, DC generator, relay, solenoid”, only one machine even has a rotor that needs timed current reversal.

Maintenance realities: where the question suddenly feels practical

Brushes and commutators are not just exam scenery. They wear, arc, and generate carbon dust. When the surface gets grooved or glazed, contact becomes uneven, local heating rises, and the motor or generator starts complaining with noise and erratic torque.

A service manual will usually ask you to check: brush length against a minimum figure, spring pressure, alignment in the holders, and the condition of the commutator surface. Cleaning might mean a specific solvent and a lint-free cloth; resurfacing might involve undercutting mica between segments or turning the commutator in a lathe.

None of that shows up in a one-line physics question. Yet it is all implied once you know those two sliding contacts and that ring are doing high-current switching at speed, in a magnetic field that is never perfectly symmetrical.

Why many new machines quietly avoid brushes and commutators

Modern designs often move away from commutators entirely. Induction motors, synchronous machines, and brushless DC motors use either AC supply or electronic switching so that no sliding electrical contact has to carry large current while switching polarity.

The logic is simple. Eliminate the brushes and commutator, and you remove brush drop losses, mechanical wear, brush dust, and the limits on voltage and current density that come with arcing contact. You also improve reliability in sealed or hazardous environments where sparking would be a problem.

Yet exams and many introductory courses still lean on the brushed DC generator and motor because they make polarity reversal very visible. You can literally point at the copper, at the brushes, and say: this is where the direction changes. That concreteness keeps the old machine in the syllabus even while industry moves on.

So what should you actually answer?

If someone hands you the question exactly as written — “Which electromagnetic device uses brushes and a commutator?” — you answer “a DC generator” and accept the mark. That is how the common question banks frame it.

If you are writing or speaking outside that narrow format, you say something slightly richer: DC machines that rely on mechanical commutation, mainly DC generators and brushed DC motors, use brushes and a commutator to manage current between the stationary circuit and the rotating armature. That statement matches what you actually see when you open the casing, not just what appears in the answer key.