Commutator Maintenance Products: How To Choose Tools That Actually Protect Your Machines

If you treat commutator maintenance products as generic abrasives and cleaners, you shorten commutator life and chase the same failures every shutdown. The gains come from using a small, deliberate set of stones, cleaners, undercutting tools and inspection aids that remove as little copper as possible, keep the film stable and make your motor behaviour predictable, not surprising.

Table of Contents

What these products really control

You already know what a commutator does, and you know the usual faults: banding, grooving, threading, high mica, heavy film, brush wear. The products in your maintenance drawer do only three things that matter: they control the surface texture of the copper, the condition of the patina, and the geometry of the bar/mica system. Everything else is packaging and catalogue language.

Most public guides stop at “clean, stone, undercut, reassemble.” Nide, EASA, and others explain cleaning techniques well: dry wiping, solvent cleaning, light abrasive work, even ultrasonic cleaning for harsh environments. The interesting part, the part that separates a long-lived commutator from a recurring problem, is how you select and combine products so that every intervention is the minimum necessary disturbance.

The main product families, seen from the shop floor

In practice, commutator maintenance products fall into a few working groups: abrasive stones and flexible abrasives, burnishing and cleaning sticks, chemical cleaners, brush seating materials, mica undercutting tools, and measurement aids. Catalogues from Martindale, Mersen, Motronic, Rimac and others are full of part numbers, but underneath them is a simple idea: different grades of abrasives and cutters are just different ways of trading speed for control.

You do not need everything. You do need the right few, specified properly, and you need technicians who know when to stop using them.

Abrasive stones and flexible abrasives

Stone selection is where many shops quietly damage commutators. Martindale’s abrasive catalogue lists several grades for brush seating and cleaning stones, from extra soft for slip rings to medium hard for undercut commutators, with clear warnings that the softest grades are not suitable for commutators at all. If your toolbox has only one “general purpose” stone, you are forced into compromise every time.

Flexible abrasive strips and brush seater blocks from Mersen and similar suppliers are built on fine-grain insulating materials. They are designed to clean patina and seat brushes while hardly touching the copper itself, and they are explicitly not machining tools. Treat them that way: clean film, tidy light streaks, refresh the track before a brush change, but do not attempt to fix geometry or deep grooving with them.

The practical rule is simple. If you are regularly seeing fresh copper after “cleaning,” you are over-stoning for the condition you have. Move down to a softer grade or a flexible abrasive, and increase the time rather than the aggression.

Cleaning sticks and burnishing tools

Cleaning sticks and burnishing brushes exist for one reason: to remove deposits and microscopic scratches without contributing new damage. Manufacturers sell carbon and resin-bonded sticks marketed specifically as commutator cleaning or rust-removing tools, often positioned alongside brush holders and springs.

Textbooks and engineering references still describe the old hardwood block method: a dense, completely dry wood shaped to the commutator radius, run across the surface after sanding to burnish out fine scratches and stabilize the film. Modern cleaning sticks are essentially purpose-made versions of that idea, with controlled abrasivity and insulating bodies.

If you finish every abrasive operation with a non-metallic burnishing tool, you leave a smoother path for the brushes and reduce the need for heavy corrective work later. It feels like an extra step; it usually pays for itself in reduced brush wear.

Solvents, chemicals and the “no lubricant” debate

Most official guidance agrees on a few basics. Use a clean, lint-free cloth for light contamination. Use an approved, residue-free solvent such as isopropyl alcohol or a chlorinated-solvent replacement when the surface is oily, and remove brushes before you do it because the carbon is highly absorbent. Make sure the commutator is completely dry before returning the motor to service.

At the same time, some older maintenance articles still recommend light mineral oil on commutators as a lubricant, while other sources clearly warn against any lubricants at all and highlight silicone in particular as a cause of abnormal brush wear.

If you want a consistent policy, pick one and document it: either a strictly dry surface with only residue-free solvents allowed, or a tightly controlled lubricant procedure that explicitly excludes silicone and is backed by your motor OEM. Mixing practices from different eras usually ends in inconsistent brush films and confusing wear patterns.

Brush seating products and why their grade matters

Brush seating is not just a commissioning ritual; it is how you reset the interface after every significant intervention. Helwig’s brush and commutator condition guide, along with several OEM recommendations, stresses that brushes should be seated to the commutator radius to achieve very high contact area before the machine is loaded.

Brush seater stones and flexible seater blocks are built with abrasives that preferentially wear the carbon, not the copper. Mersen’s tool catalog explicitly describes these brush seaters as materials that barely wear the metal and should be used with proper dust collection. When technicians substitute a generic commutator stone for seating, they often remove too much copper while barely shaping the brush.

A good rule is to standardize two or three seating products by machine size and brush grade: one gentle option for small frames and fine-grain brushes, one more robust choice for larger industrial motors, and one soft, flexible option for final contact optimization in low-current applications. The fewer choices on the cart, the more likely they are used correctly.

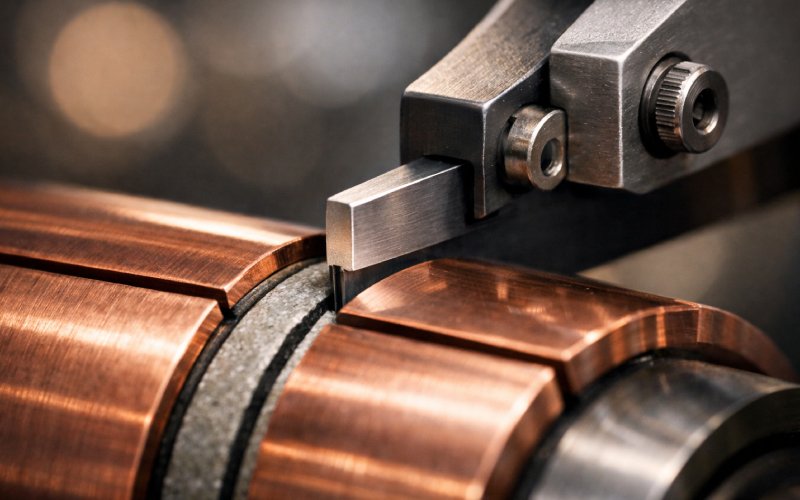

Mica undercutting tools and cutters

Undercutting products are where your risk climbs. Motronic’s commutator maintenance catalogue covers saws and “V” and “U” profile milling cutters that are explicitly intended for mica and not for copper, with thicknesses chosen to handle typical insulation gaps. Mersen lists hand slotters and slotting files, with “V” and “U” cutting edges for undercutting, burr removal and bar edge chamfering. Rimac and other builders provide dedicated undercutting machines sized from small armatures to large industrial commutators, many of them automated.

These tools are best treated as precision instruments, not grinders. The aim is to restore a clean, uniform mica recess without widening or damaging the bar edges. If you find yourself reaching for undercutters during every outage, the real issue is probably mechanical runout, inadequate brush spring control, or poor fitting of commutator bars, not mica height alone. Keep a log of where and how often you undercut; repeated use on the same machine is a reliability signal, not routine housekeeping.

How the better shops build their product set

If you compare a typical general-industry article on commutator maintenance to the detailed catalogues and technical notes from specialized suppliers, you see a gap. The public articles emphasize cleaning methods. The product catalogues emphasize part numbers. Almost nobody explains how they assemble a kit for day-to-day work.

A reliable shop usually ends up with a compact, layered set of products: a few grades of commutator stones, a couple of flexible abrasives, one or two cleaning sticks, a standard solvent, a defined undercutting setup, and a small group of measurement tools for runout and film assessment. Everything else is exceptional.

The philosophy is minimal disturbance. Start with the least aggressive tool that can achieve the required result in the available outage window, and move upward only when the surface or geometry clearly demands it. The products are not there to make the commutator pretty; they are there to keep it within a narrow, repeatable condition band.

Symptom-driven product choice

The gap between “we cleaned it” and “this commutator is healthy” is usually in how well the product choice matches the observed condition. The table below gives a condensed decision view that you can adapt into your own standard. It is not exhaustive; it is meant to nudge the thinking process.

| Observed condition on commutator | Likely underlying situation | Priority products to reach for | Key cautions when using them |

| Uniform brown patina with light streaking, no serious sparking | Film slightly disturbed by load shifts or minor contamination; geometry still acceptable | Lint-free cloth, residue-free solvent for oil traces, flexible abrasive strip or soft cleaning stick for light streaks | Keep abrasives very fine and pressure low; avoid removing visible copper; dry completely after any solvent work |

| Heavy carbon build-up, dark bands, light grooving, occasional brush noise | Overdue cleaning, dust accumulation, modest runout or brush loading issues | Medium-soft commutator stone sized to the bar width, followed by insulating cleaning stick or hardwood burnishing block | Work in short intervals and inspect; do not try to remove all historical marks in one outage; always finish with a non-metallic burnish to smooth micro-scratches |

| Pronounced bar-to-bar ridges, threading marks, persistent arcing even after cleaning | Loss of concentricity, advanced wear, possibly loose segments or thermal distress | Turning or grinding tools (including synthetic diamond tools in a commutator lathe), then light stoning and burnishing | Treat this as a refurbishment, not a touch-up; measure runout before and after; avoid deep cuts that remove excessive copper and shorten service life |

| High mica, brush chatter, rapid edge wear on brushes | Insulation not receding with copper; slots clogged or poorly undercut | Portable mica undercutter, narrow saws or milling cutters with “V” or “U” profile, fine slotting files for chamfering | Use cutters designed for mica only; control depth carefully; clean slots thoroughly afterwards to remove debris, then re-seat brushes |

| Oil or grease contamination, patched film, random light arcing | Seal leaks, over-lubrication upstream, or maintenance residue, with film partially broken | Residue-free solvent, multiple wipe-and-dry cycles, limited use of flexible abrasive to restore patina, sometimes temporary cleaning brushes | Remove brushes before aggressive solvent use; avoid silicone products entirely; do not re-introduce lubricants unless your OEM specifically calls for them |

The details in your plant will differ. The pattern holds: observe the surface, infer the condition, choose the mildest product that can realistically address it, and verify with measurements instead of just appearance.

Measuring the effect, not just the shine

Good commutator maintenance feels very ordinary when it is working; the motors run quietly, brushes last, inspections are boring. You only get that if you measure. Mersen’s carbon brush maintenance guidance, for example, recommends checking runout with a dedicated profiler and keeping total indicated runout under tight limits for many machines. Other references suggest using dial indicators, resistance tests between segments, and growler testing for shorts after significant work.

The uncomfortable truth is that many commutator maintenance products are used mostly because “it looks better afterwards.” That is not a metric. Adding a simple measurement routine around runout, bar-to-bar resistance and brush wear rate turns stones and undercutters from cosmetic tools into controlled process steps.

Avoiding the usual traps

Almost every serious guide on commutator care repeats the same warnings, usually for good reasons. EASA and several motor manufacturers explicitly advise against emery cloth with aluminum oxide, because conductive particles can lodge in the slots and promote arcing. Catalogues distinguish clearly between slip ring stones and commutator stones, with notes that the softest stones should not be used on commutators at all. Technical references warn against silicone near commutators due to abnormal brush wear.

Two behaviours cause the bulk of avoidable damage. One is using whatever abrasive is physically nearby, regardless of grade or composition. The other is using a harsh product to correct a symptom that actually comes from poor brush selection, spring pressure, or mechanical alignment. The product looks like the solution; the root cause is elsewhere.

Turning product knowledge into a repeatable method

If you look across the better articles and catalogues, a simple pattern emerges. Cleaning techniques range from dry wiping to ultrasonic tanks. Abrasive stones come in a spectrum of hardness and grit. Undercutters, slotters and saws cover every mica geometry. Brushes can even be formulated to act as temporary cleaning tools.

The difference in real-world performance is less about what is available and more about how disciplined your choices are. A small, well-defined set of commutator maintenance products, matched to your actual machine fleet and backed by a written procedure, will outperform a cabinet full of random stones and cleaners every time.

Bottom line: buy fewer products, specify them harder, use them more gently, and measure the results. The commutators quietly last longer, the brushes behave, and maintenance outages stop being a guessing exercise.