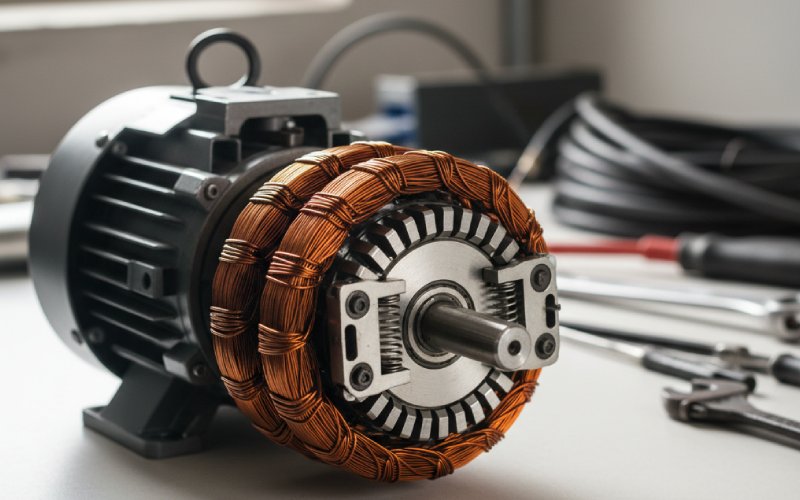

Armature winding and commutator connection

A DC machine only behaves like the design sheet says if the armature winding and the commutator agree with each other. Get that marriage right and you get clean torque, calm brushes, and predictable voltage; get it slightly wrong and the machine argues with you through heat, noise, and random sparking.

Table of Contents

Why this topic still bites experienced designers

Most guides repeat the same definitions: lap versus wave, commutator pitch, back and front pitch, progressive and retrogressive, and so on. Those are fine. They just do not tell you why a motor that is “correct on paper” still burns a couple of bars after six months in a dusty plant.

The real story sits in how the armature winding distributes potential around the periphery, how that pattern is sampled by the commutator bars, and how the brushes short-circuit small groups of coils for a very brief, slightly chaotic interval. Commutation is nothing more than controlled damage; the whole connection scheme exists to keep that damage small, fast, and evenly shared.

So instead of re-explaining what lap and wave windings are, this piece assumes you already know the formal terms and focuses on how the connection choices show up as behavior.

Lap versus wave: thinking in current paths, not just formulas

You already know the headline: lap winding gives as many parallel paths as poles, wave winding fixes that number at two. That line shows up in every textbook. The more useful view is to picture what the commutator and brushes “see.”

In a simplex lap winding on a 6-pole machine, the commutator is feeding six parallel armature circuits. Each circuit wanders around the armature, roughly aligned with one pole. Voltage mismatches between those paths are inevitable because the flux distribution is never perfectly uniform, the slots are not perfectly identical, and temperature gradients are boring but very real. The commutator bars tie all those paths together at the brushes, so any mismatch turns into circulating currents that do nothing useful and show up as extra copper loss and brush heating.

Wave winding does something more ruthless. With two parallel paths only, each path samples conductors under all poles, so the EMF seen in each path is already an average of the field irregularities. The commutator still joins the paths at the brushes, but the difference between them is smaller, and circulating currents drop without you adding a single external component.

So the quick mental rule becomes simple:

If you expect strong current and modest voltage, the armature wants many paths (lap) and very careful equalization. If you expect higher voltage and controlled current, the armature prefers fewer paths (wave) and lets geometry do most of the balancing.

This sounds almost too tidy, and it is, but it matches what repair shops actually see on the bench

Commutator pitch: starting from the brush, not the formula

Formulas for commutator pitch, (Y_c), are everywhere. You probably have them memorized: distance in bars between the two segments belonging to the same coil, with sign depending on progressive or retrogressive layout.

What tends to help more in practice is to start from the brush and walk around the periphery in your head.

Imagine one positive brush spanning two commutator bars. At any instant, that brush is short-circuiting the coil (or coils) connected to those bars. The layout of the winding decides whether that shorted group sits mostly under one pole or is spread across several.

With a lap winding, the “shorted” coil group tends to sit inside one pole pitch. That makes the commutation problem very local: one pole, one group of conductors, one strong change in current.

With a wave winding, the bars touched by a brush often collect coil sides from several poles, so the shorted group is more distributed, and each conductor is switching a smaller portion of its rated current. The commutation interval is the same mechanically, but the stress per conductor can feel gentler.

So, when you choose commutator pitch, do not only check closure and progression conditions; check what set of physical coil sides is shorted when one brush covers two bars. If that set lives entirely under a region of bad flux distortion, sparking is going to arrive whatever the math says.

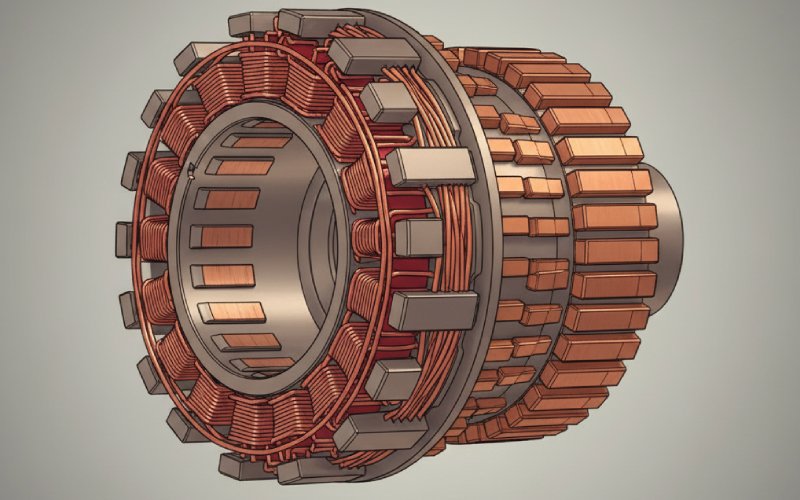

Equalizer rings, dummy coils, and quieting the machine

Lap windings on multi-pole machines have an annoying habit: because each parallel path is mostly tied to one pole, any variation in flux or slot impedance causes circulating currents between paths. Equalizer rings are a quiet fix. They connect commutator segments that should sit at the same potential if the machine were perfectly balanced, forcing the parallel paths to average themselves.

These bars do not carry full-load current; they just bleed away difference currents. When they are missing, loose, or badly brazed, you often see localized bar burning and uneven brush wear that is hard to explain from external load alone.

Wave windings carry a different sort of baggage: dummy coils. Since the winding must close neatly around the armature with a pattern that crosses all poles, sometimes the slot count does not divide in the neat way the equations want. Designers then insert non-connected “coils” purely to keep mechanical balance and slot fill reasonable.

So, during rewind work, treating dummy coils as disposable copper and equalizer rings as optional hardware is a fast path to a machine that looks right and runs badly. They are part of the connection scheme, even if they carry little or no load.

Commutation as a design test, not a troubleshooting last resort

From the theory point of view, ideal commutation means current reversal is finished while the brush still covers both bars of the shorted coil, so no sparking, no extra loss, and no bar damage.

In practice, the winding and commutator layout give you only a few levers over this:

You decide how many conductors are in the shorted group at any one moment. You decide the resistance and inductance of that group. You decide how evenly the induced EMF along the commutator circumference helps or hinders the reversal.

Everything else—brush grade, brush spring pressure, interpoles, compensating windings—comes in later as corrections or upgrades.

A useful habit is to think of commutation during the winding design itself. If your layout puts a large inductive group under a strong and distorted field at the instant of commutation, you are betting that brush grade and interpoles will save you. They often can, but they should not have to.

What actually goes wrong: connection patterns behind sparking

Most maintenance notes list the usual causes of sparking: wrong brush position, incorrect spacing, contaminated commutator surface, mica not undercut, loose bars, and so on. Those are real and common. But underneath, there is often a connection story that started at the winding table.

When a rewound lap machine returns from repair with bars burning in a repeating pattern—say, every fifth segment—the odds are good that the parallel path structure has changed. Maybe a supposed equalizer ring is mis-positioned. Maybe the progression direction flipped from the original, moving the active brushes relative to the neutral plane without anyone noticing.

When a wave-wound armature that used to run quietly now sparks at light load, a surprisingly frequent culprit is an attempt to “simplify” dummy coils or to reuse an old commutator with a new slot count. The winding may still close, but the effective commutator pitch seen by the coils is slightly off, so different groups experience different induced voltages during commutation.

These are not the failures you can fully fix with a brush stone and a vacuum cleaner. They are connection topology problems that need you to trace the scheme and compare it to the original design, bar by bar.

Progressive, retrogressive, and why direction matters less than consistency

You know the definitions: in progressive windings the path moves in the same direction as the armature rotation when you follow the connection through the commutator; in retrogressive it moves opposite. Both can be made to satisfy closure conditions for lap and wave layouts.

From a performance standpoint, direction mostly affects where the brushes must sit relative to the mechanical neutral and which slots happen to be in commutation under a given pole. If you accidentally switch a machine from progressive to retrogressive during rewinding without moving brush gear, the neutral zone shifts and commutation quality changes, even though all the local pitches still check out numerically.

So the design note is short: pick one scheme, stick to it across the fleet, and record it clearly. The commutator does not care which label you choose; the maintenance crew cares a lot.

A compact comparison of armature–commutator schemes

Sometimes a table is faster than prose. Values are indicative, not strict rules.

| Aspect | Simplex Lap Winding | Simplex Wave Winding | Notes for Commutator Connection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical parallel paths (a) | (a = P) (number of poles) | (a = 2) for all pole counts | Parallel paths define how many “armature circuits” the commutator must feed. |

| Current / voltage tendency | High current, lower voltage machines | Lower current, higher voltage machines | Not a rule of physics, more a manufacturing habit that matches path structure. |

| Need for equalizer rings | Strong, especially for (P \ge 4) | Usually none | Equalizers connect bars that should be equipotential, cutting circulating currents. |

| Use of dummy coils | Rare | Common when slot and bar counts do not line up nicely | Dummy coils keep slot fill and mechanical balance; they stay unconnected to the commutator. |

| Coils shorted during commutation | Typically one coil per brush width | Often multiple coils under different poles | This changes the inductance of the shorted group and the way interpoles assist commutation. |

| Repair sensitivity | Very sensitive to equalizer and brush layout errors | Very sensitive to commutator pitch and dummy coil treatment | Both punish “almost right” rewinds; they just complain in different patterns. |

Design and rewinding checkpoints that usually pay off

A few habits tend to separate stable machines from the ones that keep returning to the workshop. None of them are complicated, and they are mostly about slowing down during connection planning.

Trace one complete path from a positive brush, through all the coils in that path, to the negative brush, on your drawing. Confirm that every coil side in that path experiences a reasonable distribution of poles, not just one overloaded region.

Count how many conductors sit in the shorted group when a brush covers two bars. If that number is high and those conductors lie in a part of the air-gap with high armature reaction, consider changing brush width, adding interpoles, or re-examining the winding type before the machine is built.

Treat equalizer rings and dummy coils as functional elements, not decorations. Their absence or casual relocation explains more mysterious sparking stories than exotic theory ever will.

And finally, write down the progression direction, commutator pitch, and brush positions in a way that someone else can reconstruct five years later. Winding diagrams get lost; a clear record of how the armature talks to the commutator saves entire weekends of reverse-engineering.