6-Step Commutation in BLDC Motors: What Actually Matters in a Real Drive

Six-step commutation is not fancy, but it moves a lot of products. If you get the switching table, sensing, and timing right, you usually ship. If you miss on any of those, no amount of theory fixes the noise, the missed steps, or the random resets on the bench.

Table of Contents

Why engineers still pick 6-step when they know FOC exists

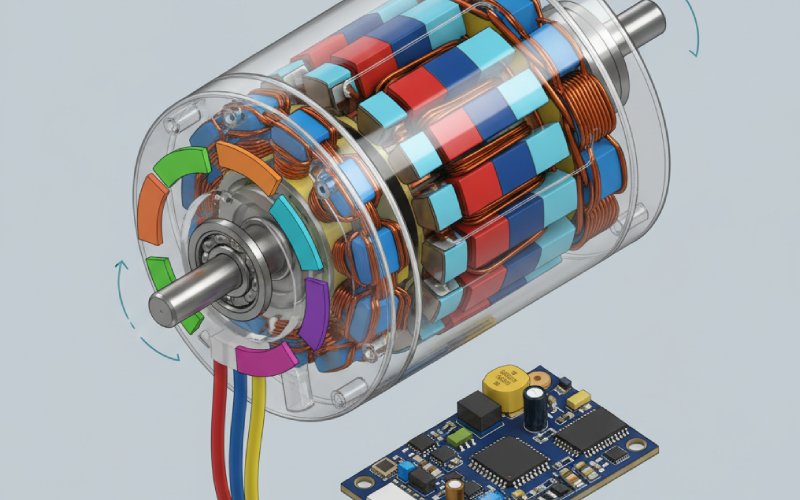

Textbooks and vendor slide decks keep pointing at field-oriented control as the end state. Then you walk into an appliance, power tool, fan, pump, or low-cost robot and see a simple three-phase bridge, a small MCU, three Hall lines, and a 6-step table burned into flash. Trapezoidal control (120° block commutation, 6-step) stays around because it does a few things very well: high top speed, low computational load, and simple fault handling.

The Microchip and Onsemi notes both say the same thing in slightly different language: six discrete stator field positions per electrical cycle, only two phases driven at a time, one phase floating, and the rotor magnet just keeps chasing that field around. TI then adds the obvious but often ignored detail: this method usually gives you the highest maximum speed and very low gate-driver complexity, at the cost of torque ripple and acoustic noise.

If you are reading this, you likely know all of that already. The value now is in the details you do not usually see in the “intro to BLDC” documents: how to build and debug the commutation table, how to choose a PWM scheme that matches your hardware, and how to make sensorless 6-step not misbehave at low speed.

Electrical sectors, pole pairs, and why your angle math keeps biting you

Microchip’s documentation spells out the convention clearly: six sectors per electrical cycle, 60 electrical degrees per sector, and one electrical cycle per rotor pole pair per mechanical revolution. You know the formula, but in software it has a bad habit of getting “sort of right” and then drifting.

If the motor has (N_p) pole pairs, one mechanical revolution is (N_p) electrical cycles. So a Hall sensor transition every 60 electrical degrees becomes every 360/(6Np) mechanical degrees. Easy on paper. In firmware, this is where engineers quietly sprinkle constants until the speed estimate matches the tachometer.

Six-step logic itself does not care about absolute angle in degrees. It only needs a sector index from 1 to 6 (or 0 to 5) and a desired rotation direction. That is the privilege of crude methods: no Park transform, just “we are in sector 3, we want to go forward, so we energize these two phases in this polarity and leave the third phase high-Z.” MathWorks’ motor control blockset essentially formalizes this into a block that maps Hall state to sector and then to switch states, with a torque angle target of about 90° ± 30°.

If you treat the sector index as the core state and let everything else derive from it, your code often ends up simpler than if you keep carrying angles around.

A practical 6-step commutation table you can actually code

Every vendor app note has some version of a 6-step table. TI’s Hall-based commutation note shows the pattern clearly: three digital Hall signals, six valid states, one mapping from that state to phase polarities, and one phase left floating. MathWorks then shows almost the same mapping but in terms of AA′, BB′, CC′ gate commands.

Here is a compact version you can lift directly into a lookup table. This assumes phases are named U, V, W and Halls are A, B, C. The mapping is for one rotation direction; reversing the order of steps in firmware reverses direction.

| Step (sector) | Hall (A B C) | High-side ON | Low-side ON | Floating phase |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 0 1 | U | V | W |

| 2 | 1 0 1 | U | W | V |

| 3 | 1 0 0 | V | W | U |

| 4 | 1 1 0 | V | U | W |

| 5 | 0 1 0 | W | U | V |

| 6 | 0 1 1 | W | V | U |

Two small but important notes follow from this table.

First, invalid Hall codes (000 or 111, or any pattern not in the table if your wiring is odd) should be treated as faults or “no commutation” states. TI explicitly recommends using Hall states as indexes into a software lookup table and treating unexpected values as error conditions, not as “best effort” drive attempts. Allowing random patterns to map to arbitrary gate states is a subtle way to destroy MOSFETs.

Second, the table assumes a particular alignment between mechanical rotor position and Hall transitions. If your Hall sensors are wired differently, or the rotor magnet is glued down in a different orientation than you expected, the state sequence will rotate or invert. You then either rewire phases, remap Hall lines, or rotate the firmware table. This is where many designs spend an afternoon.

Using the table as firmware, not just as a drawing

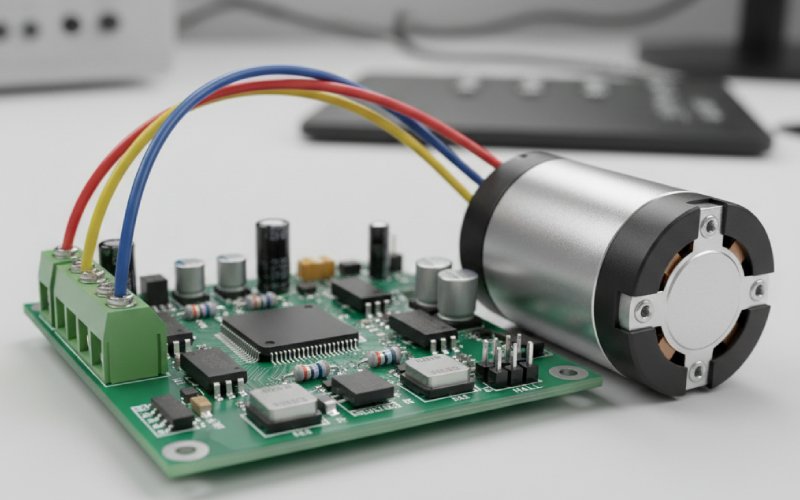

The nice thing about a 6-step table is that you can let it drive both power stage and control logic. The raw Hall bits form a 3-bit index. That index gives you three things at once: which high-side gate to PWM, which low-side gate to PWM or clamp, and which phase is high-Z for potential BEMF measurement in a sensorless design.

It is tempting to encode only the high-side phase and infer the rest. Resist that temptation. Putting the full gate pattern in the table per step makes debugging trivial: you can print or log the full pattern and cross-check it against the expected waveforms from vendor diagrams. MathWorks’ example explicitly lays out the switching sequence bits per sector; copying that pattern into a C struct or LUT is about as low-risk as this gets.

Once the table is in place, most of the control code reduces to three operations: decode Hall to sector, pick row for direction, apply PWM duty to the active legs. All the “control theory” sits one level up, deciding what the duty should be to meet speed or current targets.

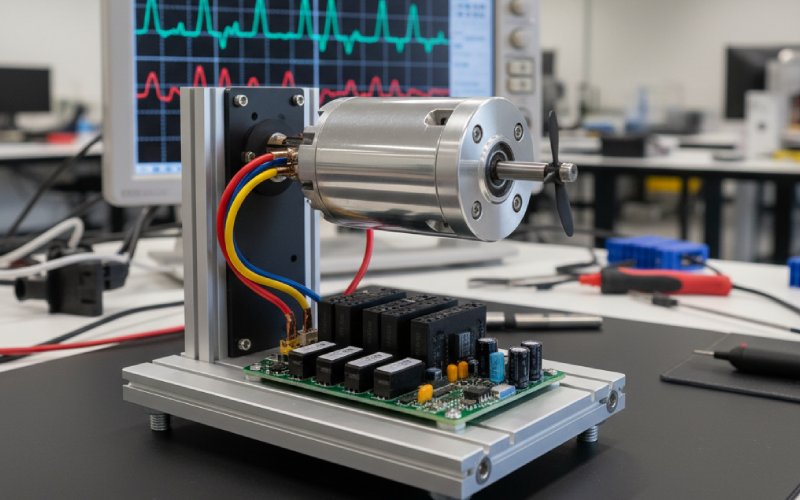

PWM schemes for 6-step: picking the least bad compromise

Microchip’s motor control documentation summarizes three very common PWM schemes for six-step commutation. The text looks like marketing, but the trade-offs are real:

One scheme drives the high side of one active phase and the low side of the other at a time, with fixed on/off on the opposite legs. It is simple, has low switching loss, and does not need dead time between complementary devices, but it tends to produce high current ripple.

Another scheme uses complementary PWM on one active phase while holding the low side of the other phase fully on. This keeps switching loss low on one leg, but you now must manage dead time and deal with more complex current waveforms.

The third scheme drives both active phases with complementary PWM. That reduces current ripple and can give better torque smoothness, but at the cost of higher overall switching loss and stricter dead-time management.

Renesas adds a variant they call “balanced PWM,” where both positive and negative legs for a given phase share the chopping duty in each conduction period, equalizing switching stress and reducing torque ripple. The idea is simple: if one device switches significantly more than its partner across the mechanical life of the product, that device ages faster. Balanced schemes aim to distribute stress more evenly.

In practice, on a low-power fan driver, the first scheme is often more than enough. On a higher-current power tool or automotive pump, the third or balanced scheme tends to work better, and the dead-time complexity is small compared to the cost of audible current ripple or EMI issues.

Sensored 6-step: Hall wiring, calibration, and direction

Most practical 6-step designs still start with Hall sensors. TI, NXP, Microchip, NXP again; they all show the same archetype: three digital Hall latches spaced 120 electrical degrees apart (or mechanically spaced accordingly), feeding three GPIOs.

The interesting problems are not the Hall devices themselves; they are wiring and calibration:

First, the three motor phase leads and the three Hall outputs can be wired in six permutations each. Monolithic Power Systems even shows a neat table of all six possible motor phase lead configurations (A-B-C, C-A-B, B-C-A, and so on). Combine that with arbitrary Hall connector pinouts and you get a puzzle where the software sees a valid six-state pattern, but the order in which those states appear around the electrical cycle might not match your “ideal” table.

Second, to get clean torque, you want the Hall transitions roughly 30 electrical degrees before or after the ideal commutation instant, depending on your chosen phase advance. MathWorks explicitly suggests a “Hall sensor sequence calibration” procedure to discover the actual sequence and align it with the commutation pattern. In the lab, this usually means slowly spinning the motor with a fixture or another motor, logging Hall states and phase voltages, and building the true sequence from measurement rather than from assumptions.

Direction is mostly bookkeeping. If the motor spins the wrong way, you can swap any two phase leads, invert the direction flag in firmware, or reverse the order in which you cycle through the six steps. Swapping two phases and leaving the Hall wiring alone is the instinctive hardware fix; reversing the table is the lower-risk firmware fix.

Sensorless 6-step: BEMF detection, blanking, and the low-speed cliff

Vendor notes from TI, ST, and Renesas all show the same sensorless 6-step picture: the undriven phase carries an induced voltage (back-EMF), the controller compares that voltage to some reference (often half the DC bus), and the zero crossing marks the right time to commutate.

In real hardware, a few details decide whether it works or just buzzes:

At each commutation, the previously conducting coil needs time to demagnetize. During this demagnetization interval, the “floating” phase is not really floating; the terminal voltage is swinging because the current in the other phases is changing. ST’s app note shows how the low side of the voltage envelope rises as the BEMF polarity flips, and why sampling too early leads to incorrect zero-cross detection. Blanking time after each commutation is not fluff; it is essential.

PWM complicates that further. If you sense BEMF during low-side off time (true high-Z on the terminal), your effective sampling window shrinks with duty cycle. Some designs instead sense during on-time using a reference at half the DC bus, as ST notes, which trades analog circuit complexity for a wider sensing window at high duty cycles.

Then you have the low-speed problem. No rotation, no BEMF. The TI training slides spell it out: sensorless six-step methods do not work where torque is needed at or near zero speed. Starting strategies become a separate subsystem: align the rotor by forcing a static field, blind-start with an open-loop ramp, or briefly inject high-frequency pulses to infer initial position. You may never show that logic in a block diagram, but it is usually the difference between “starts reliably” and “sometimes twitches.”

Speed and current loops on top of 6-step

Six-step itself only defines which transistors are on. It does not care whether the motor runs at 300 rpm or 30 000 rpm. Control loops on top handle that.

The simplest case is open-loop duty control: you treat duty cycle as a crude proxy for torque and accept whatever speed the load and supply allow. For fans and some pumps, that is good enough.

Anything that needs regulated speed or torque adds at least one feedback loop. A common pattern in application notes is an outer speed loop (PI controller closing on measured speed from Hall edges) that updates a torque or duty reference, and an inner current loop or protection scheme that keeps phase current within limits. Microchip’s motor control literature describes both open-loop and closed-loop approaches and includes hardware support such as cycle-by-cycle current limiting in the PWM module.

Strict current control is not mandatory for every six-step drive. Mechanical inertia and load tolerance sometimes hide a lot of electrical imperfection. But once you push into higher torque density or want predictable transient response, a basic current loop around the PWM duty starts looking less like a luxury and more like the only way to keep the system within thermal and EMI constraints.

Debugging 6-step on the bench: a routine that actually finds faults

Most 6-step issues fall into a short list: wrong Hall sequence, dead or swapped phases, missing dead time, bad BEMF timing, and supply or ground problems. You can see all of them if you watch the right signals.

A practical routine looks something like this, even if you do not write it down. First you probe DC bus and gate drive supply to make sure the power stage is behaving at a basic level. Then you scope Hall lines while mechanically turning the rotor; you should see six clean states, with no illegal code held for more than a few microseconds. If you see 000 or 111 staying around, you have wiring or sensor issues before any control algorithm even runs.

Next you overlay phase voltage (or phase-to-phase voltage) with Hall transitions. The transitions should occur at consistent positions relative to the six-step sequence shown in vendor diagrams; if they are offset by a constant amount, you can correct the commutation angle in software. If the pattern is rotated or reversed, you fix the wiring or rotate the lookup table.

For sensorless drives, you also watch the undriven phase and the comparator output, verifying that detected zero crossings line up with the expected midpoints of the flat regions in the phase voltage envelope, as in the ST and Renesas figures. When timing drifts with temperature or load, the problem is often in the analog front end, not the MCU code.

When all of that looks reasonable, you turn to current. Measure phase current ripple for each PWM scheme you try; compare it with the trade-offs listed in the Microchip and Renesas notes. You will usually find that the cheapest scheme in code is not the cheapest in magnetics and EMI filters.

Where 6-step fits against sinusoidal and FOC

TI’s “Demystifying BLDC commutation” deck lays out the hierarchy: trapezoidal (6-step) at the simple end, sinusoidal in the middle, and FOC at the complex end. We can restate the practical version without charts.

If the application cares mostly about cost, has modest acoustic requirements, and can accept torque ripple, six-step is usually enough. It wins on computational load and often on maximum achievable electrical speed, especially when implemented with simple gate drivers and MCUs. Onsemi’s application note echoes this: trapezoidal control is one of the simplest methods available and offers good peak performance for many industrial loads.

Once you need lower noise, better partial-load efficiency, or smoother torque, sinusoidal control starts to look more attractive. When you need tight torque control across a wide speed range, field weakening, or maximum energy efficiency, you end up in FOC territory and six-step becomes the fallback mode or start-up mode, not the main method.

It is less a question of which method is globally “better” and more a question of which parts of motor behavior your product actually pays attention to.

Summary for your next design

If you approach 6-step as “the simple option,” it tends to misbehave in all the usual ways. If you treat it as a discreet, state-based control algorithm with specific timing and measurement constraints, it looks more like a robust subset of more advanced methods.

Build your commutation table from real Hall or BEMF data, not just from a diagram. Choose a PWM scheme that matches your magnetic and thermal limits, not just your MCU’s timer block. Treat sensorless start-up and low-speed behavior as a separate design problem, not as a minor tweak. And keep a standard bench routine for verifying Hall patterns, phase voltages, and BEMF timing before you blame any of the control loops.

Six-step commutation then stops being a quick hack and becomes a deliberate design choice. Which is usually where reliable products come from.